Better from Russia than via Croatia: the future of oil supplies to Hungary and Slovakia

In July, the Russian oil company Lukoil ceased its oil supplies to Slovakia and Hungary due to sanctions imposed by Ukraine. This situation has brought the two countries’ dependence on Russian oil into the spotlight (see ‘Hungarian-Slovak Dispute with Ukraine: Suspension of Lukoil Oil Supplies’). Slovakia and Hungary are exempt from the EU’s sanctions on Russian oil, which have been in effect since December 2022, in order to enable them to gradually abandon their reliance on oil imports from Russia.

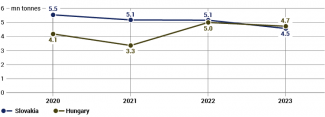

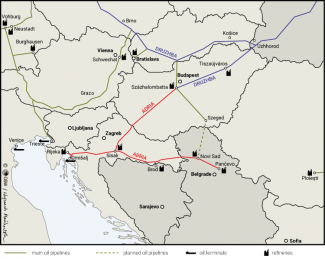

Since then, Slovakia has made only a marginal reduction in its previously full dependence on Russian oil, whereas Hungary has even temporarily increased its oil imports from Russia (see Chart). Budapest appears determined to maintain as close an energy partnership with Moscow as possible, criticising both the government in Kyiv for obstructing the import of Russian oil and the European Commission for approving such actions. Furthermore, Hungary has questioned the credibility of alternative supplies via the Adria oil pipeline, which originates from the Omišalj oil terminal on the Adriatic Sea in Croatia (see Map). The Hungarian authorities have also played a significant role in the diversification of oil supplies to Slovakia, as the country’s sole oil refinery is owned by Slovnaft, a subsidiary of the Hungarian energy company MOL.

Croatia has emphasised its readiness to increase oil supplies to both Slovakia and Hungary, stating that it could fully meet the demand of the two refineries operating in these countries. This message was publicly conveyed on 1 August by Croatia’s Prime Minister, Andrej Plenković, in a letter addressed to the prime ministers of Hungary and Slovakia, as well as to the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen. However, Hungary’s Foreign Minister, Péter Szijjártó, dismissed the offer as “unreliable”.

Hungary’s reluctance to diversify its oil supply sources

Since the outbreak of the full-scale war in Ukraine, Hungary has maintained its near-unchanged energy dependence on the Russian Federation. Regarding oil, an alternative supply route via the Croatian oil terminal currently accounts for approximately 30% of Hungary’s oil imports. However, Budapest has not taken any decisive steps to increase this proportion. During a 2022 debate on sanctions against Russia, MOL estimated that fully adapting the Százhalombatta refinery near Budapest to process non-Russian oil would take between two to four years. However, no further information regarding the progress of this adaptation has been published.

The Hungarian authorities have stressed that the capacity of the Adria oil pipeline (11 mn tonnes annually) is insufficient to meet the combined demand of the refineries in Hungary (8.1 mn tonnes) and Slovakia (6.1 mn tonnes). They have also criticised the ongoing modernisation of the pipeline’s 80 km-long Sisak–Virje section. Furthermore, Budapest has accused Croatia of imposing “fees five times higher than the average market rates”, after 2022, which, according to Hungary, undermines Zagreb’s credibility.

Both the Croatian government and the operators of Croatia’s oil transmission network have refuted Hungary’s accusations regarding insufficient capacity, excessive fees, and Zagreb’s alleged lack of credibility as a partner. They have highlighted the long-standing cooperation between JANAF and MOL, during which both parties have consistently fulfilled their mutual obligations. This includes the terms of a contract for the transport of 2.2 mn tonnes of oil, valid until the end of 2024, which also covers supplies to Slovnaft.

According to unofficial sources cited by the Croatian edition of ‘Forbes’ magazine, Hungary was offered a new long-term contract, likely with more favourable financial terms, but it declined the offer. The Croatian side has also emphasised that, through the use of drag-reducing agents (DRA), which reduce turbulence in the pipeline during oil flow, the Adria pipeline is capable of transporting 14.3 mn tonnes of oil annually to Hungary—an amount that fully meets the combined demand of the Hungarian and Slovak refineries. JANAF’s CEO further refuted Hungary’s claims, noting that in February 2023, representatives from MOL participated in technical tests of the pipeline, which confirmed that its capacity was 1.2 mn tonnes per month, or 14.4 mn tonnes annually. This, according to JANAF, renders Hungary’s accusations unfounded.

According to JANAF, the allegations made by Budapest regarding excessive fees are part of the MOL group’s negotiating strategy. The Croatian company maintains that the price for oil transport is determined through negotiations, based on an undisclosed methodology that factors in the length and utilisation level of each specific section of the pipeline. Therefore, the fees for oil supplies from the Croatian terminal should be economically advantageous for Hungary, as the pipeline to the Hungarian border is only 289 km long (compared to the nearly 700 km section of the Druzhba pipeline that runs through Ukraine). Additionally, transporting oil through a region affected by hostilities carries a risk of supply disruptions.

However, Hungary is employing all available means to maintain its oil imports from the Russian Federation. According to announcements from Budapest, a solution is expected to be in place by mid-September that will enable the resumption of Lukoil’s oil transit through Ukraine. Under this plan, Russian oil could once again be transported to the Hungarian and Slovak refineries, with MOL becoming the legal owner of the oil as soon as it enters Ukrainian territory. MOL would also assume responsibility for ensuring the security of the transmission along this section. The arrangement would incur additional costs for the Hungarian company, as it would need to secure insurance at an estimated cost of around $1.5 per barrel.

Cooperation overshadowed by disputes

Hungarian-Croatian cooperation has been hindered by an energy dispute that has persisted for more than a decade. According to the Croatian government, in 2009, MOL assumed control of the Croatian company INA, which holds a dominant position in Croatia’s oil and gas sector, through corrupt practices. A court in Zagreb sentenced the CEO of the Hungarian company, Zsolt Hernádi, to two years of imprisonment. However, the Hungarian government has refused to extradite him for several years.

Another long-standing dispute between Zagreb and MOL concerns the status and future development of the INA company. Successive Croatian governments have unsuccessfully attempted to repurchase MOL’s stake in the company Zagreb has criticised MOL for closing the refinery in Sisak, one of two such facilities in Croatia. In June, the Hungarian company launched its fourth arbitration case against Croatia, having won two previous cases, with another still pending.

In this latest case, MOL accuses the Croatian government of forcing INA, through a decree, to sell all domestically produced gas in 2022-2023 at below market prices to HEP, a 100% state-owned electricity producer. In response, Zagreb argued that its actions were driven by the energy crisis caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and were fully compliant with both Croatian and EU legislation.

Outlook

Long-standing disputes over INA continue to overshadow Hungarian-Croatian relations. Strengthening cooperation on oil imports from Croatia will require political will from Budapest. Additionally, restoring mutual trust and developing a comprehensive, sustainable plan for oil supplies from the Adriatic terminal to Hungary and Slovakia will be essential. This plan must be predictable and mutually beneficial for all parties concerned, perhaps requiring the involvement of third partners such as the EU.

The continuation of oil supplies from Russia, facilitated by Hungary’s exemption from the EU embargo, was advantageous for Hungary, as this oil was sold at a lower price. The price difference per barrel ranged between $5 and $30, depending on the specific period after the imposition of sanctions. In 2022, the MOL group reported a record operational profit of $4.7 bn (with $3.1 bn in 2023), allowing it to strengthen its market position over regional competitors, mostly ORLEN and Austria’s OMV. The Hungarian state budget also benefitted from this arrangement through the windfall tax collected from MOL’s extra profits.

Budapest is hopeful that once the war in Ukraine ends, relations between the West and Russia will return to their previous state, negating the need for diversification of oil and gas supplies. Furthermore, the Hungarian government has no intention of halting the expansion of the Paks nuclear power plant, which is being carried out by Russia’s Rosatom. As a result, Hungary remains committed to maintaining its energy supplies from Russia, despite the risks associated with oil transit via Ukraine and the growing political cost stemming from increasing distrust among its Western partners.

Although Slovakia has reduced its reliance on Russian oil from 100% in 2021 to around 90% (according to Eurostat) or approximately 75% (according to statements by Slovnaft and the Slovak government) in 2023, it remains committed to continuing these imports. In this context, Slovakia is to some extent constrained by MOL and its policies, which are in turn heavily influenced by Viktor Orbán’s government. MOL, as the entity responsible for signing key supply contracts and controlling the Bratislava refinery, also sets the timeline for transitioning to alternative oil types.

Additionally, the government of Robert Fico, which has governed Slovakia since autumn 2023, has shifted the country’s stance, offering political support to Budapest’s actions—unlike previous administrations. It has also criticised Zagreb for not providing clear assurances regarding the price and potential volume of oil supplies. Similar to Budapest, Bratislava has accused the European Commission of supporting Ukraine over Slovakia and Hungary in disputes over the suspension of Lukoil’s oil supplies. Despite this, the Fico government has continued to pursue positive relations with Kyiv. The third meeting between the prime ministers of Slovakia and Ukraine is scheduled for autumn this year.

The stance of Hungary and Slovakia contrasts sharply with that of the Czech Republic, which is also exempt from EU sanctions. From the beginning of 2025, the Czech Republic will have an alternative source of oil supply through the TAL pipeline, originating in Trieste, capable of fully meeting the demand of both Czech refineries. Over the past three years, the Druzhba oil pipeline has accounted for between 49% and 58% of the Czech Republic’s total annual oil imports. Prague has expressed its commitment to completely phase out Russian oil as soon as it becomes technically feasible (see ‘The TAL is expanding: the Czech Republic is gaining independence from Russian oil supplies’).

Chart. Volume of oil imported from Russia to Hungary and Slovakia, 2020–2023

Source: the authors’ own calculation based on figures compiled by Eurostat.

Map. Oil supplies to Hungary and Slovakia via the Adria and Druzhba oil pipelines

Source: the authors’ own analysis.