The US budget battle: a crucial test for Republicans

A battle is under way in the United States Congress over the shape of the federal budget for the 2025 fiscal year. The Donald Trump administration’s stated goal is to balance the budget and reduce public debt. Its approach centres on significant spending cuts, alongside increased revenues expected to result from higher tariffs and measures to stimulate economic growth. To achieve the targeted scale of expenditure reductions, the administration will likely need to cut funding for healthcare and social welfare programmes – a move that could have serious electoral consequences for the Republican Party.

Although the defence secretary has announced cuts to Pentagon spending, overall defence expenditure is likely to increase in the near future, particularly with regard to modernisation. However, the planned savings will contribute to a decline in US global influence, as evidenced by the dismantling of most USAID programmes and attempts to shut down media outlets such as Voice of America. The administration’s fiscal agenda is intended not only to improve the country’s budgetary position, but also to overhaul the US economic model and reshape international trade. The drastic tariff hike announced by the president on 2 April is expected to play a key role in this strategy.

Tax and spending cuts

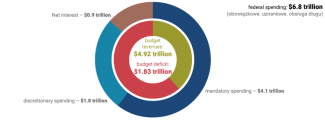

According to Donald Trump, the fate of the country and the future of successive generations of Americans depend on balancing the federal budget as swiftly as possible. The US Congressional Budget Office forecasts that deficit in the 2024 fiscal year reached $1.83 trillion (6.6% of GDP), while public debt exceeded $35.2 trillion (122% of GDP).[1] Interest payments on the debt currently account for 8% of annual federal government expenditure. Without radical changes, the debt will continue to rise rapidly due to the costs associated with statutory obligations – primarily healthcare, Social Security, and other social programmes, as well as the increasing cost of debt servicing.

The administration’s approach to reducing the deficit centres on boosting budget revenue, initially through higher tariffs and, over the longer term, through economic growth driven by the reindustrialisation of the United States. The tariff hikes are intended to spur companies to relocate production to US territory. Additional incentives include favourable fiscal conditions created by the extension of the tax cuts introduced by the first Trump administration in 2017, as well as deregulation and low energy prices anticipated as a consequence of the administration’s efforts to promote the exploitation of domestic oil and gas reserves. This strategy will be complemented by new initiatives such as ‘gold cards’, which offer permanent residency – and potentially citizenship – to individuals who invest $5 million in the country, and the establishment of a sovereign wealth fund to invest in state-owned assets.

At the same time, the current administration is seeking to implement federal spending cuts totalling up to $1 trillion by downsizing the federal workforce and trimming departmental budgets. President Trump has assigned this task to the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), a newly established body headed by Elon Musk. Despite DOGE’s aggressive efforts during the new administration’s initial weeks in office, Musk has so far fallen far short of the targeted $1 trillion in savings. According to the department’s own estimates, the cuts currently amount to approximately $130 billion,[2] although the actual figure may be lower. Bridging the gap to the $1 trillion target would require legislative changes. However, implementing such reforms could prove politically difficult and costly, as they would likely involve reductions in funding for healthcare, social programmes, and defence.

Efforts to balance the budget are further complicated by Trump’s campaign promise to extend the tax cuts introduced during his first term, which are set to expire at the end of this year. The 2017 legislation primarily reduced personal income tax and lowered the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. The president is now seeking to cut corporate tax further, potentially to 15%, in order to make investment in the United States more profitable. He also proposes to introduce exemptions related to tips and overtime pay. These proposals are expected to cost at least $5 trillion over the next decade.[3]

Republicans seek greater control

As the federal budget had not been passed before the start of the 2025 fiscal year (1 October 2024), a continuing resolution adopted in late December 2024 remained in effect when Trump took office; it expired on 14 March this year (see Appendix 2). Republicans succeeded in passing a new continuing resolution that extends government funding until the end of the current fiscal year (30 September). It is based on the previous year’s budget, with several adjustments: an increase of approximately $6 billion in defence spending and a reduction of around $13 billion in other areas[4] (see Appendix 2). The document does not include the kind of drastic spending cuts previously proposed by figures such as Elon Musk; however, such cuts may still be introduced in the near future.

Trump has previously demonstrated his willingness to challenge decisions made by the US Congress and expand executive authority by freezing funds allocated by the legislature for specific purposes, such as foreign aid, even though such actions are prohibited under the 1974 Impoundment Control Act. The president may also use existing legal mechanisms to submit a request to Congress to cut spending already authorised by budget legislation. Such a proposal must be approved by the appropriations committees and then passed by both chambers of Congress. However, only a simple majority is required in the Senate, meaning that Republicans could enact such cuts without Democratic support. Musk discussed this option at a meeting with Republican senators in early March.

In parallel with work on the continuing resolution, the Republican Party has launched a separate process aimed at enabling it to implement budget changes in the second half of the fiscal year through the so-called reconciliation procedure. The Senate can pass a reconciliation bill by a simple majority, unlike standard legislation, which requires at least 60 votes and therefore necessitates bipartisan agreement. As a result, reconciliation is often used to advance the core elements of an administration’s political agenda. In this case, the reconciliation bill (or bills) would cover immigration – including funding for deportation operations and strengthening border security – as well as energy and defence, particularly the procurement of weapons systems and military equipment for the Navy and Air Force. The process is also expected to encompass the aforementioned tax proposals.

Republicans also need to address the issue of the debt ceiling. In the United States, once the statutory debt ceiling is exceeded, the government is no longer permitted to borrow further, even if this prevents it from meeting existing obligations. To avoid default, Congress has repeatedly raised this ceiling. In 2023, the United States reached its debt limit of $31.4 trillion, and the Republican majority in the House of Representatives initially refused to approve an increase. As part of a compromise, the ceiling was suspended until 1 January 2025. It is now back in force, albeit at a level that includes the debt accumulated during the suspension; unless Congress raises it, the risk of default will re-emerge in the coming months. However, raising the limit is highly unpopular among fiscal hawks within the Republican Party, and it is also difficult to reconcile with the broader narrative of balancing the budget and reducing public spending.

Implications for domestic, foreign, and security policy

This year’s budget process is of central importance to the entirety of the Trump presidency. Republicans are aware that next year will be dominated by campaigning for the midterm elections scheduled for November 2026. These elections often result in losses for the president’s party, meaning that Republicans may find themselves in a weaker position during the second half of Trump’s term. The approaching elections may also prompt some members of theHouse and the Senate to adopt a more rigid stance towards the president’s policies. Therefore, the most challenging elements of his political agenda will need to be implemented within the current year.

The Republicans’ narrow majority in the House of Representatives and their lack of a 60-vote majority in the Senate leave them reliant on alternative methods for advancing sensitive reforms, such as reconciliation. To realise this strategy, they will need to ensure coordination between the House and the Senate and accommodate the demands of various factions within their camp. Any success in implementing significant cuts to mandatory spending – particularly healthcare programmes for low-income Americans – may come at a political cost. Even suggestions of reductions to Medicaid, a programme that provides healthcare coverage for vulnerable groups, have provoked a fierce public backlash.

The Trump administration will face a major challenge in its effort to reshape the United States’ trade relationships – a core element of the president’s political agenda. On 2 April, Trump announced a baseline 10% tariff on imported goods, while also applying the principle of reciprocity by imposing significantly higher duties on countries he believes maintain unfair barriers against US exports. As a result, the United States’ trade-weighted average tariff rate has surged from 2.5% last year to 23% – a level not seen since the 1920s. The current administration is expected to continue with its protectionist trade agenda, although tariff levels may be subject to future negotiations. Further increases are also likely in response to retaliatory measures imposed by trading partners.

The budget cuts will also reduce the United States’ ability to project influence through soft power. In its first weeks, the new administration effectively dismantled the US Agency for International Development (USAID), which had been responsible for the bulk of US foreign aid. In early March, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced that 83% of the programmes funded through the agency would be cancelled, and that the State Department would assume responsibility for the remainder. The administration has also taken steps to drastically curtail the activities of the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM), which could result in the closure of outlets such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. However, a court has temporarily blocked this move pending judicial review. Trump also plans to significantly reduce the State Department’s budget and staffing levels. His administration is reportedly considering reductions in embassy and consular staff, and even the closure of certain diplomatic posts. This reflects not only a drive for cost savings, but also the belief that soft power tools have previously been used to promote a leftist agenda abroad.

With regard to the Department of Defense, in February the Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, announced cuts totalling 8% of its annual budget. However, this likely involves a reallocation of the resulting savings to areas aligned with the administration’s priorities. Hegseth has already cancelled programmes worth approximately $800 million, including projects aimed at decarbonising naval vessels, increasing diversity within the Navy and managing civilian personnel through software that was deemed excessively costly.[5] Both the most recent continuing resolution and proposals linked to the reconciliation process indicate that overall defence spending is likely to increase, enabling faster modernisation of the Air Force, Navy, and the nuclear arsenal.

APPENDIX 1. The US budget deficit and public debt

In the 2024 fiscal year, federal government spending totalled $6.75 trillion, while revenues reached $4.91 trillion. As a result, the deficit stood at $1.83 trillion. The United States last recorded a budget surplus in 2001. Since then, the federal budget has remained in deficit, peaking at $3.13 trillion in 2020. During the 2020s, the deficit has not fallen below $1 trillion.[6]

US public debt has reached levels not seen since the end of the Second World War – in 1946, it stood at 119% of GDP. The current period of rapid debt growth began in the 1980s, driven by reduced tax revenues and soaring defence spending. This trend was briefly reversed during Bill Clinton’s second term thanks to the budget surpluses achieved during that period. Debt levels began rising again as a result of several factors, including the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and especially the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession. The situation improved after 2012, but the need to stimulate the economy affected by the COVID-19 pandemic once again accelerated the growth of federal debt.

APPENDIX 2. The US federal budget and the budget approval process

Chart 1. The US federal budget in fiscal year 2024

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

US federal spending is divided into mandatory and discretionary categories. The former includes expenditures arising directly from previously enacted legislation, primarily Social Security (pensions and disability benefits), healthcare and other social programms; which are not subject to change through the annual budget process. Discretionary spending accounts for just over one-quarter of the federal budget. Approximately half of this is allocated to defence, while the remainder covers other areas of government activity, including education, transportation, and environmental protection.

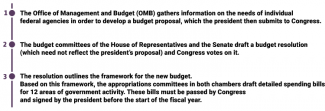

Chart 2. The US federal budget process

Source: the federal budget process, usa.gov.

The fiscal year in the United States runs from 1 October to 30 September. The 12 required appropriations bills are almost never passed on time. To facilitate the legislative process, several of them are often combined and voted on as part of a single package known as an omnibus bill. Despite this, budget work is rarely completed before the start of the new fiscal year. As a result, continuing resolutions, which extend government funding for several months or even until the end of the fiscal year, have become standard practice. Failure to pass a continuing resolution on time leads to a government shutdown, which forces federal institutions to scale back operations to the bare minimum. Over the past two decades, the threat of a shutdown has frequently been used as leverage in cross-party negotiations.

[1] The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, Congressional Budget Office, 17 January 2025, cbo.gov.

[3] ‘Trump Tax Priorities Total $5 to $11 Trillion’, Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 6 February 2025, crfb.org.

[4] ‘H.R.1968 – Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025’, United States Congress, 15 March 2025, congress.gov.

[5] M. Olay, ‘Hegseth Addresses Strengthening Military by Cutting Excess, Refocusing DOD Budget’, U.S. Department of Defense, 20 February 2025, defense.gov.

[6] ‘Federal Surplus or Deficit’, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 31 March 2025, fred.stlouisfed.org.