Greenland: a unity government in Nuuk and the American dream of the Arctic

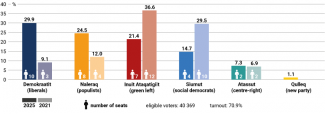

The early parliamentary elections held on 11 March in Greenland, an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, have reshaped the local political landscape. The liberal Democrats scored an unexpected victory, winning 29.9% of the vote and increasing their seats in the 31-member parliament from three to ten. The election marked a defeat for the governing coalition of the left-wing Inuit Ataqatigiit (21.4%) and the social democratic Siumut (14.7%), which together lost 11 seats (see Chart). In the face of US claims to the island, on 28 March the Democrats’ leader and incoming Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen announced the formation of a broad coalition comprising four of the five parties represented in parliament.

The presentation of the new government was overshadowed by the first-ever visit of a US vice president to Greenland, which took place on the same day. J.D. Vance, accompanied by National Security Advisor Mike Waltz and Energy Secretary Chris Wright, visited the US Pituffik Space Base in the north-western part of the island. In a speech delivered against the backdrop of renewed international competition in the Arctic, Vance outlined Washington’s new approach towards Greenland, continuing the policy of containing Russia and China in the polar regions, which was initiated during Donald Trump’s first term as president (see ‘NATO’s polar quartet. The US, Canada, Denmark and Norway in the Arctic‘).

Government of national unity

The formation of a broad coalition in Greenland is intended to demonstrate unity in the face of US pressure and to strengthen the message of the island’s right to self-determination. The new cabinet is dominated by parties advocating a gradual assumption of responsibilities from Denmark, while increasing the island’s economic independence based on revenues from fisheries, tourism, and mining. At present, subsidies from Copenhagen account for roughly half of the autonomous government’s budget revenue. The political majority is aware of Greenland’s limited financial and human resources and does not wish to pit the cross-party aspirations for independence against the benefits of the welfare state sustained by the union with Denmark. Nielsen’s government will prioritise pragmatic and stable cooperation with Copenhagen, not least because many Greenlanders are weary of the sense of mounting crisis surrounding the island. As a result, the prospect of an independence referendum has been postponed beyond the upcoming parliamentary term, which begins on 7 April (2025–29). Naleraq, a rising populist party calling for an immediate launch of independence proceedings, has opted not to join the cabinet.

The coalition agreement outlines support for private enterprise within an economy dominated by Greenlandic state-owned companies, where public administration and services account for nearly half of all employment. It also provides for greater fiscal discipline and tax reform, investments in healthcare and education, and the establishment of an expert council for the development of the fisheries sector, which accounts for over 90% of the island’s export value. One of the key priorities in external relations will be to assume greater control over the Kingdom of Denmark’s polar policy, a goal that will be facilitated by the country’s upcoming chairmanship of the Arctic Council, beginning in May. However, the ideologically diverse coalition is certain to face internal friction, including over foreign affairs.

A false start for the United States

Vance’s visit to Pituffik confirmed a redefinition of US policy towards Greenland. The United States is likely to pursue closer bilateral ties with the island and support its moves towards independence. The presence of the Energy Secretary and the National Security Advisor suggests that the Republican offer to Greenland will centre on investment in the island’s mining sector and the development of the US Arctic military capabilities, particularly naval power through the expansion of the icebreaker fleet. The Vice President clarified that there are no plans to increase permanent US military presence in Greenland. Efforts to strengthen bilateral cooperation are aimed at creating conditions under which Greenlanders might ultimately opt for a union with the United States. The form such an arrangement might take has not been specified, although Washington has experience managing Compacts of Free Association agreements with island nations in the Pacific. The United States views Greenland as part of its broader strategy to contain Russia and China in the Arctic, across military, economic, and trade domains, in the context of future polar navigation.

In the near term, however, US policy towards the island is unlikely to deliver the results that the Trump administration would like to achieve. In the early weeks of his presidency, the United States squandered much of the political capital it had built through establishing closer cooperation with Greenland in recent years. According to public opinion surveys, an overwhelming majority of the island’s population (85% of respondents) oppose joining the United States. The idea also faces broad opposition within the US itself: a poll conducted for Fox News in March indicated that 70% of Americans are against it.

In fact, the United States does not require a change in Greenland’s status to expand its military and economic footprint on the island. The 1951 Danish-American agreement on the defence of Greenland allows the US to shape its military presence on the island with considerable freedom. Similarly, potential investments in the mining sector face few external constraints (apart from uranium extraction) since the island’s autonomous government has assumed full responsibility for managing the extraction of mineral resources. Furthermore, Greenland’s economy is not subject to EU regulations, as the island withdrew from the European Communities in 1985. At present, of the 85 active mining licences in Greenland, only one is held by a company registered in the United States.

Reactions in Greenland...

Rising US pressure to take control of the island has mobilised local civil society. On 14 March, party leaders issued a joint statement condemning Trump’s rhetoric. The following day, large anti-American demonstrations took place across Greenland. The island’s initial restraint and emphasis on closer cooperation with the US gave way to more assertive responses. Concerns over potential US interference also prompted legislative action. In February, Greenland’s parliament banned anonymous and foreign donations to political parties and introduced restrictions on property purchases by non-residents. Several public institutions in Greenland subsequently suspended ongoing cooperation with the United States.

These developments culminated in Greenland’s response to the announcement of a visit by Second Lady Usha Vance, who was scheduled to attend the 29 March National Dogsled Race in Sisimiut, co-sponsored by the United States. Although the visit was officially described as private, it was confirmed that Waltz and Wright would accompany her. Amid mounting public opposition and planned protests, Washington’s decision to deploy two aircraft carrying personnel and equipment to safeguard the visit further inflamed tensions in Greenland, where such security measures are rare. Greenlanders viewed the cancellation of the original programme and the decision to confine the visit to the US base as a political success and a reaffirmation of their agency in shaping the island’s relationship with the United States.

At the same time, Greenland seeks closer relations with the US, grounded in respect for its right to self-determination. From Greenland’s perspective, these ties hold considerable untapped potential, albeit in areas largely unrelated to great power rivalry in the Arctic. Greenland is primarily interested in establishing air connections, developing a commercial maritime route, and attracting investment in the mining sector. The Republican narrative concerning alleged Chinese and Russian influence in Greenland has been met with bewilderment on the island. Although Russia and Denmark/Greenland have overlapping claims to the Arctic Ocean’s continental shelf, Russia has not engaged in the types of provocations witnessed in the Baltic region, such as airspace violations and incidents involving critical underwater infrastructure. Moreover, two Chinese-backed mining projects have ended in failure, with Greenland withdrawing the licences: one involving Chinese participation in an Australian-led rare earths venture, and the other concerning the acquisition of an iron ore deposit. Efforts to expand scientific cooperation with China have also proved unsuccessful.

...and in Denmark

The election’s outcome has provided Denmark with both an opportunity and additional time to recalibrate its policy towards Greenland. On top of continuing its current approach and further increasing Greenland’s involvement in Copenhagen-controlled Kingdom’s foreign and security policy, it may also consider reshaping the Realm’s internal structure from unity into an association of sovereign states with distinct constitutional arrangements. In such a model, Denmark would retain certain prerogatives, such as defence, and uphold its social obligations. Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s visit to Greenland (2–4 April), presents an opportunity to set the scene for initiating this process in the future.

Although in recent weeks the Danish media have drawn comparisons between US actions and Russia’s behaviour prior to its annexation of Crimea, Vance’s speech was received in Copenhagen with cautious relief. Despite its accusatory tone towards Denmark regarding the alleged neglect of the island’s defence, Danish leaders welcomed Vance’s affirmation of the Greenlanders’ right to self-determination and their right to decide the country’s future, as well as his avoidance of any reference to the use of force. Notably, he also refrained from questioning Denmark’s sovereignty over the island under international law.

Contrary to Republican rhetoric, Denmark has significantly increased its spending on military capabilities for Arctic operations in recent years. In January, it allocated an additional €2 billion for this purpose and pledged further investment. It has also expanded the presence of its armed forces in Greenland, largely as a result of pressure from the first Trump administration. Moreover, Denmark provides capabilities of real value to Greenland, including fisheries inspection, UAVs reconnaissance, search and rescue operations, and the deployment of environmental protection vessels. A voluntary military training programme introduced on the island last year has also proved popular.

Denmark accepted the red lines drawn by the United States in 2018, when the Department of Defense pressured the Danish government to block Chinese investments in airport infrastructure on the island (see ‘Wrestling in Greenland. Denmark, the United States and China in the land of ice‘). It also remains open to any US initiatives aimed at strengthening military cooperation in the Arctic and in Greenland (see ‘The crisis over Greenland: Denmark’s response to Trump‘).

Chart. Results of parliamentary elections in Greenland in 2021 and 2025

Source: Municipality Election 2025, qinersineq.pl.