No Azerbaijani gas to Central Europe

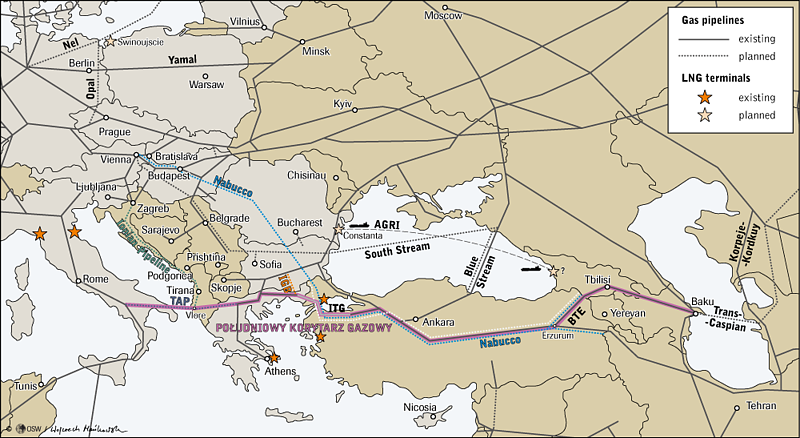

On 26 June the Austrian holding, OMV announced that the consortium operating in Shah Deniz, the largest gas field in Azerbaijan, had not selected the Nabucco West project as its route for Azerbaijani gas to Europe. Despite there being no official information from Azerbaijan, it appears that the preferred route for gas supplies to Europe will be via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP).TAP is to run from Greece, through Albania, to Italy. Its capacity will be 10 billion m3 with the possibly for this to be doubled. It is predicted to cost approximately US$ 1.5 billion and is several times cheaper than Nabucco West. TAP has gained exemption from the European Commission’s Third-Party Access rule. This means that the consortium engaged in the project has full transmission powers at its disposal. TAP’s shareholders are: Switzerland’s Axpo – 42.5% (previously called EGL), Norway’s Statoil – 42.5% (Statoil also holds shares in the Shah Deniz consortium), and Germany’s E.ON Ruhrgas – 15%. According to an agreement made in November 2012, Azerbaijan’s SOCAR, BP and Total have the option to jointly acquire 50% of shares in the TAP project upon it being chosen as the route for the transmission of Azerbaijani gas. The first gas supplies from Shah Deniz are scheduled for 2019.

Commentary

-

The fact that TAP has been chosen indicates that gas from Azerbaijan will be exported to markets along the route of the pipeline (Greece, Albania, Italy) and also to the countries of the Western Balkans (Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, which still de facto require the…) via the Ionian Pipeline currently under construction. Furthermore, due to the connector under construction from Greece to Bulgaria (IGB – it has a capacity of 5 billion m3 of gas annually and is scheduled for completion in 2014) there will be the possibility to deliver gas to the Bulgarian market and from there onwards to Romania and Hungary along connectors currently existing or under construction. Export to the countries of Western Europe (e.g. Austria and France) are also possible due to the network of Italian pipelines and “swap” agreements.

-

SOCAR is likely to win a tender to allow it to take over Greece’s gas network and LNG terminal – this was key in influencing the decision to reject Nabucco West, which would have delivered gas directly to Baumgarten in Austria. By entering the Greek market and gaining access to the LNG terminal, SOCAR will have a wider range of options for future gas markets. The rejection of Nabucco West seems to have been based on the greater options available for deliveries to individual markets connected to the TAP route and beyond – this is key considering the changes taking place on the EU market (a fall in demand, shale gas).

-

The rejection of the Nabucco West route also means that the EU’s plans to reduce Central Europe’s dependence on Russian gas have suffered a tremendous defeat (despite giving formal backing to all the projects of the Southern Corridor, in practice the EU was supporting Nabucco). While it is true that supplies to Central Europe may still be made via the network of interconnectors, they are of negligible significance and do not have any geopolitical burden. In this context the rejection of Nabucco West may be seen as Azerbaijan wishing to avoid a clash with Russia’s Gazprom, whose South Stream project is mainly targeted at the same markets as Nabucco. Following the decision to build the TANAP route independently through Azerbaijan and Turkey and to reject Nabucco West, the EU can no longer view the Southern Gas Corridor as an instrument to create a system in the Caspian Sea region and the Middle East (where the gas fields are located) and it has thus become an instrument mainly to realise Azerbaijan’s interests.

Map. Southern Gas Corridor