Crisis in Ukraine: the first step towards compromise

After several days of clashes in the centre of Kyiv between protesters and officers of the Berkut and the Interior Ministry, on 23 January President Viktor Yanukovych agreed to hold direct talks with the leaders of the three political parties, Arseniy Yatseniuk (Batkivshchyna), Vitali Klitschko (UDAR) and Oleh Tiahnybok (Svoboda). Over four rounds of talks, a preliminary compromise was agreed upon, including the resignation of the government, the repeal of the anti-democratic laws adopted on 16 January, amnesty for the protesters, and for work to begin on the restoration of the parliamentary-presidential system. The authorities did not agree to early presidential or parliamentary elections, and the leaders of the opposition did not accept the offer to join the government (Yatseniuk had been offered the position of prime minister). On 28 January, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov resigned and parliament repealed the anti-democratic laws during an extraordinary session. However, on the 29th, the attempt to adopt a compromise version of the law on amnesty failed; in the face of opposition protests, the version put forward by the Party of Regions was passed, making any amnesty conditional on the protesters leaving the government buildings they have occupied. Also, the attempt to establish a working group on constitutional reform failed. These failures threaten the informal truce which has been holding on the Maidan.

The government’s willingness to hold talks with the opposition was caused by the mobilisation of protesters showing their strength on the Maidan and on Hrushevsky Street in Kyiv, as well as the escalation of protests in the regions. In the past ten days, demonstrators have taken over control of government buildings in ten regions, mainly in western and central Ukraine. Of particular significance was the outbreak of mass protests in some areas in the eastern and southern parts of the country, particularly Dnepropetrovsk, Odessa, Cherkassy and Lugansk. This has significantly strengthened the opposition’s negotiating position. The government’s move to a position of greater compromise has been influenced by the rise of discontent within part of the ruling elite, who favour a peaceful solution to the crisis and an agreement with the opposition.

The concessions which the authorities have made so far do not mean the end of the political crisis, but they do give hope that a return to its most violent forms can be avoided. The political opposition fears the reaction of the Maidan, which it controls to only a small extent, and so it will continue to try to force the government into making further concessions, including not only an unconditional amnesty, but also agreement to early parliamentary elections, and at maximum presidential elections as well. President Yanukovych’s camp will draw out the negotiations for as long as possible, and his willingness to make further concessions is very limited. The shape of a possible constitutional reform, the new government and the possible involvement of opposition politicians in it all remain open questions.

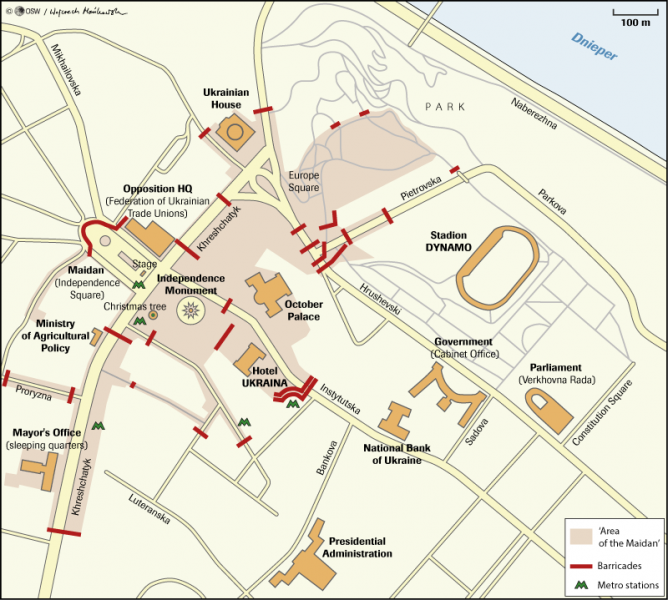

Developments in Kyiv

On the evening of 19 January, a confrontation began between demonstrators and police on Hrushevsky Street, near the headquarters of the parliament, and continued uninterrupted until noon on the 23rd, when Vitali Klitschko negotiated a truce between the leadership of the protesters and senior police officers. The clashes on Hrushevsky Street were fairly equally matched between the security forces (mainly the Berkut special militia) and a group of the Maidan’s self-defence corps numbering several thousand. The police repeatedly tried to break through the barricades and push the demonstrators off Hrushevsky Street, but the demonstrators’ counter-attacks proved to be effective, and ultimately they maintained their positions. On the same evening there was a repeat of the clashes, but on 24 January a new truce was negotiated, which so far has held.

During the previous clashes there were four confirmed deaths among the protesters, who probably died from bullets fired by police snipers (the authorities reject any responsibility for this), and another activist from the Maidan was kidnapped and murdered by unknown assailants. Hundreds of people were wounded or injured on both sides. A total of over a hundred people have been arrested, and several have been reported missing for several days, including some protest leaders (including Dmytro Bulatov, a leader of the Automaidan vehicle protest).

During the clashes, the police used gas and stun grenades, smooth-bore weapons (both rubber and metal bullets), stones and even Molotov cocktails. The Maidan’s self-defence was extremely efficient and well-organised; the protesters, equipped with helmets, mainly used stones and Molotov cocktails, as well as air guns, although much less often. The protesters erected barricades, further widening the area under their control. After a failed attempt by the police to seize the Ukrainian House in the immediate vicinity of Hrushevsky Street on the night of 25/26 January, the demonstrators occupied European Square and surrounded it with barricades. These cannot be crossed without the use of heavy equipment and the possibility of large-scale bloodshed. The number of permanent occupiers on the Maidan has remained constant, and probably numbers between six and ten thousand.

The outbreak of protests in the regions

On 22 January, opposition leaders, announcing the creation of a rump parliament (the People's Council), called for the creation of similar councils in the provinces. This appeal, as well as public outrage at the fatalities in Kyiv, resulted in the occupation of regional offices of state administration and mass protests in a number of cities. In Western Ukraine the offices were occupied without resistance. The opposition seized regional administrations and created People's Councils in Lviv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, Uzhhorod, Chernivtsy, Lutsk, Rivne, Zhytomir, Khmelnytsky and Vinnytsia, that is, the whole western part and some of the centre of Ukraine, as well as in Chernihiv, Poltava and Sumy (although in the latter city the police succeeded in repulsing the attack). A special situation arose in Lviv, where the mayor has openly supported the protest; an example of this is his refusal to raise any objection to protesters blocking access to the Interior Ministry troops’ barracks.

The further east one looks in the country, however, the stronger the resistance from the armed forces has been, and the smaller the number of protesters. Nevertheless, demonstrations numbering several thousand and blockades of offices also took place in Dnepropetrovsk, Zaporozhye, Odessa, Cherkassy and Lugansk. The only regions where there have been no major protests are the Donetsk oblast and Crimea (apart from some demonstrations by Crimean Tatars in Simferopol). The unexpected outbreak of protests in the southern and eastern regions, on a scale hitherto unreported in this part of the country, has contributed to the authorities’ greater willingness to talk with the opposition, and has prevented them from claiming that the protests are happening only in Kyiv and some western regions.

The attempt to defuse the political crisis in Kyiv resulted in a weakening of protest activity in the regions. The anti-government demonstrations in the east of the country slowed down, in connection with the increasing mobilisation of local authorities and the brutal breakup of the demonstrations by the police and hired hooligans (the so-called titushky) in Zaporozhye and Dnepropetrovsk, as well as routs of smaller protests in other towns. In some regions loyal to President Yanukovych, forces appear to be mobilising in preparation to repel a possible new wave of protests.

The situation in western Ukraine, especially in Lviv, is now characterised by a determined will to continue resistance until the departure of President Yanukovych.

Four rounds of negotiations

On 23 January direct negotiations were initiated between President Yanukovych and the three leaders of the opposition; Justice Minister Olena Lukash, the new head of the presidential administration Andriy Kluyev and his deputy Andriy Portnov also attended. A breakthrough in the talks occurred on the 25th, during the third round of negotiations, during which the government proposed that Arseniy Yatsenyuk assume the position of prime minister, and the leader of UDAR, Vitaly Klitschko, that of deputy prime minister; the release and amnesty of those detained during the demonstrations; a start to talks about the revision of the constitution; and changes to the anti-democratic laws passed on 16 January, in exchange for an end to the protests. However, the opposition rejected these conditions as being not nearly sufficient to stop the protests. Yanukovych’s proposals were based on the assumption that in its current form the opposition would have to reject them, also under the influence of the Maidan, which has responded to the offer very negatively, demanding unequivocal rejection. It seems that the proposals were a manoeuvre by Yanukovych aimed at gaining time, disturbing the protest camp and preventing early presidential elections. However, the parties agreed to convene an extraordinary session of parliament on 28 January.

27 January saw the fourth round of negotiations between President Yanukovych and the opposition, during which the authorities agreed to abolish the anti-democratic laws of 16 January, adopt a law on amnesty which will only come into force if the opposition ceases its occupation of government buildings, and start work on constitutional reform. The terms of the compromise presented by the government have strengthened the opposition, but they are far from satisfactory. The government’s willingness to make concessions was also caused by growing discontent in the ruling elite, proof of which came in a statement by Rinat Akhmetov (issued by his company SCM) emphasising that the crisis can only be solved through peaceful means. It confirmed that a dispute exists within the Ukrainian elite as to how to resolve the conflict, which President Yanukovych must take into account in his calculations. In addition, reports have emerged that dozens of deputies from the Party of Regions, mainly those with ties to Rinat Akhmetov and Dmytro Firtash, have threatened to leave the party.

Extraordinary session of parliament

On 28 January, even before the formal start of the parliamentary session, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov was reported to have tendered his resignation, which President Yanukovych accepted a few hours later. According to the law, the work of the government ‘in the state of resignation’ will be directed by the First Deputy Prime Minister Serhiy Arbuzov; a new government must be appointed within sixty days. We may expect the new prime minister to be a compromise choice, acceptable to both the authorities and the opposition.

During the extraordinary session of parliament, the ten anti-protest acts adopted on 16 January, in flagrant violation of the constitution, were repealed. 361 deputies voted in favour; the Communist Party members and 22 deputies from the Party of Regions abstained. Subsequently, the parliament also voted for a package reinstating four of the same laws (257 deputies voted in favour, Svoboda and most of UDAR abstained). Two of the measures relate to issues which are important, but not relevant from the point of view of the current conflict: the abolition of VAT on gas imports, and a delay on a free legal aid programme coming into force. The two other laws are Communist projects (the protection of war monuments and a ban on ‘falsifying’ the history of the Second World War), the adoption of which was the Communists’ price for their support of the whole package of laws.

In the afternoon of the 29th, in contradiction to the preliminary information, the parliament’s deputies failed to reach an agreement concerning the compromise amnesty law, or on creating a committee on constitutional change (namely a transition from a presidential to a parliamentary-presidential system). Late in the evening of the 29th, the parliament accepted a bill based on the proposal put forward by the Party of Regions that the amnesty would be conditional upon the protesters leaving the public buildings they have occupied in Kyiv and the regions within 15 days. The motion was passed by the Party of Regions, the Communists, and some independent deputies (232 votes in all). The opposition voted against the motion, stating at the same time that it did not consider itself bound by the law, and that they would not abandon the occupation of the buildings. This has made relations between the government and the opposition significantly worse, which has pushed back the likelihood of a resolution to the conflict. The extraordinary session of parliament has now been closed, and normal proceedings will resume on 4 February.

Prospects for the Ukrainian crisis

The first concessions by President Yanukovych confirm that the option of violence, which some activists in the Party of Regions and members of the armed forces had been urging a few days earlier, is now no longer being considered. Taking that step would not bring about a pacification of the protests, but rather their escalation to much more dangerous levels. Also, and no less important, the use of force would lead to even deeper splits within the ruling elite. However, we can now assume that tension between the government and the opposition will now deepen over . The amnesty law passed by the government is unacceptable to the opposition and will not calm the mood of protest or lead to the ‘dissolution’ of the Maidan. Further concessions from the authorities – such as restoring the parliamentary-presidential constitution of 2004, and possible early parliamentary elections under a revised electoral law – will require a further weakening of Yanukovych’s position, including further splits within the parliamentary ranks of the Party of Regions.

The resignation of the government does not mean the end of the political crisis, but it does reduce the likelihood of a return to its most acute phase, the use of force. The opposition, under pressure from the Maidan, will try to force the authorities to make further concessions. President Yanukovych, in turn, will try to drag out the negotiations, consolidate his power base and undermine the mobilisation of the protest movement. His willingness to make further concessions will depend on the balance of power in parliament, which currently cannot be guessed at. From the point of view of the authorities, it is essential to prevent the calling of early presidential elections.

Maps