Russian military intervention in Crimea

During the night of 27/28 February, a military operation began in Crimea with the aim of Russia taking military control of the peninsula, an act which meets the criteria of an act of armed aggression against Ukraine. This was carried out by units of the Black Sea Fleet stationed there, together with other Russian army units transported onto the peninsula from Russian territory, supported by divisions of the so-called Crimean Self-Defence. They took over most of the strategic facilities, such as airports, road junctions and fords. They also took control over part of the infrastructure and equipment of the Ukrainian army and security structures (mainly border guards). However, most of the Ukrainian military units in Crimea have not succumbed to pressure to come under the control of the de facto authorities of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (dependent on Russia), or to withdraw from the peninsula. They have been blocked into their barracks by units of the Russian army and the Crimean Self-Defence, who have made regular attempts to take control of locations in Ukrainian hands by force. So far there has been no direct armed conflict (both parties have avoided the use of weapons), which will undoubtedly facilitate any possible peace settlement.

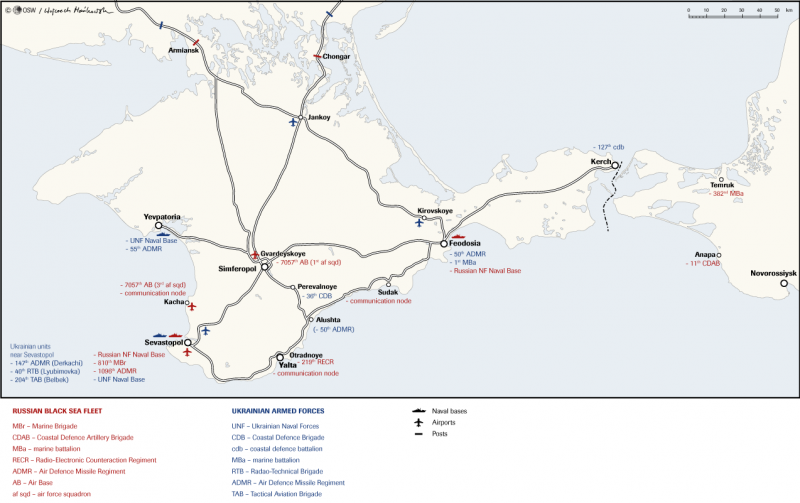

The balance of power. Russian capacity reinforced

At the start of the operation, the Russian and Ukrainian forces in Crimea were numerically relatively closely balanced (14,600 Ukrainian soldiers and sailors vs. 15,000 Russians). The size of the Black Sea Fleet was far superior in the fields of maritime and air capabilities, as well as in terms of their quality of equipment and level of training. In the last days of February, the Russian advantage began to increase steadily, with the creation of branches of the so-called Crimean Self-Defence, as well as by bringing in additional units from Russian territory onto the peninsula.

The Russian side initially tried to suggest that the Black Sea Fleet was neutral, and that its subunits were only protecting the Fleet’s possessions in Crimea. Meanwhile, however, from the beginning Russian soldiers were directly involved in taking over the infrastructure and blockading Ukrainian units. It is highly likely that part of the Crimea Self-Defence are Russian soldiers using their regular equipment (they can be distinguished from the regular formation by the concealment of their identification marks). It is assumed that the remainder of the Self-Defence units are largely made up of former Black Sea Fleet soldiers living in Crimea, as well as officers from Ukraine’s now-dissolved Berkut police special forces.

So far, a further 5500-6000 Russian soldiers have been transferred to Crimea from the Russian Federation, together with their weapons (either by air via the Russian military airport near Simferopol, or by sea through the port of Sevastopol and the ferry across the Strait of Kerch). The majority are soldiers from the Southern Military District bordering the peninsula; these units are the closest to the action (the 22nd Spetsnaz Brigade from Krasnodar, the 382nd Marine Battalion from Temruk), but there are also troops from other regions of Russia (the 31st Airborne Brigade from Ulyanovsk, Central Military District). Together with the self-defence formations and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea’s internal security forces, the number of Russian troops on the peninsula may be as high as 25,000 soldiers. The strengthening of the Russian forces is ongoing; according to some sources, preparations are being made to land armoured vehicles in Sevastopol, and dozens of tanks are to be transported to Crimea via the Kerch Strait (so far, the Russian troops on the peninsula ad not had any heavy weapons; their basic equipment was the BTR-80 wheeled armoured personnel carrier).

How the operation proceeded

Between 28 February and 4 March, units of the Russian army and the Crimean Self-Defence occupied most of the strategic infrastructure on the peninsula, including the Kerch ferry and the airports: the military field in Kirovskoye and the reserve field in Jankoy. They also took control of the airport in Simferopol. Russian checkpoints were deployed along the roads leading to the peninsula from the mainland (at the town of Armyansk on the road to Kherson, and Chongar heading towards Zaporozhye). On two occasions (1 and 4 March), Russian motorised columns made reconnaissance outside the territory of Crimea, in the Kherson region; one of them is very likely to have remained in the town of Henichesk on the road to Zaporozhye, 3 km past the Crimean border.

Despite rising pressure and ongoing systematic attempts to take over the bases by force, as of 5 March probably only two of the larger Ukrainian units had surrendered to Russian troops: the radio engineering company in Sudak and the border guards’ military unit in Balaklava. Russian soldiers backed by Crimean militias partially occupied the base of the 204th Tactical Air Brigade in Sevastopol (Belbek airport; the planes stationed there have, according to the de facto authorities in Simferopol, now become the property of the Crimean army); and the 174th air defence missile regiment (ADMR) in Sevastopol (on the Fiolent peninsula). Each side has given conflicting reports about two other units: the 50th ADMR in Feodosia and the 55th ADMR in Yevpatoria. The second of these has not yet been entirely taken over by the Russians. Further Ukrainian army bases in Sevastopol have been surrounded and blockaded (the Ukraine Navy headquarters, the ships at anchor in the Streletsky Gulf and the Fiolent reconnaissance unit relocated to the peninsula), and units in Bakhchisaray (probably an airforce engineers battalion), Perevalnoye (the 36th Coastal Defence Brigade) and Feodosia (the 1st Marines Battalion), as well as the internal army barracks in Simferopol. The situation at Belbek airport near Sevastopol is atypical; since 4 March, at least in part, the base has been under joint Ukrainian/Russian control (agreement has been reached on the organisation of mixed patrols among other matters).

Since 28 February, negotiations have been going on between the leadership of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and the Naval Command of Ukraine, also stationed in Sevastopol, most likely on the withdrawal of the Ukrainian army from Crimea. The failure of these talks is shown by the attempts which have been undertaken since 3 March to take over the Staff Headquarters of the Ukrainian fleet in Sevastopol. Probably only a small part of the Ukrainian army’s soldiers and sailors capitulated and went over to the new Crimean authorities. Reports of a mass defection by Ukrainian soldiers to the other side (allegedly 6000 soldiers by 4 March) were contradicted by the fact that the Ukrainian army has retained control of most of the major individual bases, and have effectively counteracted Russian attempts to take them over.

The military action is being accompanied by an open psychological information war. Both sides explain any ambiguity in the current state of affairs to their own advantage; Ukrainian reports that the Russian side has failed to take over their bases are more likely to be confirmed as true. The report on March 3 from Interfax-Ukraina, referring to a source in the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence that an ultimatum had been served by the command of the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea to the blockaded units of the Ukrainian army, was most likely a piece of deliberate misinformation. According to the alleged ultimatum, if they did not surrender by 5 am on 4 March, Russian units were to storm all the bases under their control. This information was denied by Russia. It is possible that this report influenced the parties' positions during the debate in the UN Security Council which took place also on 3 March.

The military context of the operation

The actions in Crimea were accompanied by increased military activity in both the Russian Federation and Ukraine. In both cases, this proves that preparations are being for a possible escalation of the conflict. On the Russian side, the visible manifestations of this have been as follows: the build-up of Russian army units in districts bordering on Ukraine’s territory, and the likely retention on standby of the Land Forces units assembled after 26 February for exercises in the Western Military District. The Ukrainian side is primarily preparing a mobilisation of the Armed Forces, as announced on 2 March.

On 26 February, large-scale exercises by the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation began in the north-western part of Russia (a total of 150,000 soldiers were to attend all elements of the exercises). Despite information showing that these were merely routine training exercises, at least in the run-up, in media coverage they were explicitly linked with the situation in Ukraine from the beginning, and presented as part of Russian pressure, or as preparations for a possible military operation against Ukraine. The possibility that the units on exercises could have been sent against Ukraine was shown by the lack of any signals, for several days, confirming the start of exercises at training grounds in the Western Military District by units of the 20th Army, the strongest operational formation of the Russian Ground Forces. Two mechanised brigades of the 2nd Army (the 15th and 23rd) of the Central Military District were transferred from the Samara region to areas bordering with Ukraine in the direction of Kharkov (officially, to training grounds in the Kursk region). It is possible that the above-mentioned army units were – and, despite an order to return to their permanent locations after the exercises still are – on standby for possible incursion onto Ukrainian territory in case the conflict escalates. Since the beginning, a direct relationship with the situation was shown by the build-up of units from the Southern Military District, especially at the high points of the Donetsk region. In both directions (Kharkov and Donetsk), breaches of the border were noted as of 1 March, both by Russian motorised columns and aviation units.

On 2 March, the authorities in Kyiv decided to put the Armed Forces of Ukraine in a state of high alert, and to start mobilisation. On the same day, supplementary military command units began sending out call-up notices. Military units also began to report the arrival of reservists, without waiting for an official call-up. For procedural reasons the commands have been unable to keep up with the registration of incoming volunteers. It is assumed that the mobilisation, including basic preparations, will last at least until the end of this week. Most likely, the rapid response units (about 20,000 soldiers) have already achieved full capacity to perform combat tasks; these are the only part of the Ukrainian army which is relatively well trained and equipped. Some of them (including a battalion of marines) remain blockaded in Crimea.

The operation’s legal aspects

By starting a military intervention in Crimea and trying to escalate the situation in the south-eastern regions of Ukraine, Russia has violated at least three bilateral agreements:

- ‘On friendship, cooperation and partnership’, of 31 May 1997 (the legal basis for Russian-Ukrainian relations);

- ‘On the status and the conditions of residence on Ukrainian territory of the Russian Federation’s Black Sea Fleet’, of 28 May 1997;

- ‘On the parameters of the division of the [Soviet] Black Sea Fleet’ of 28 May 1997.

Russia has violated at least five articles in the first of these agreements. These relate to:

- violation of territorial integrity (Article 2);

- breach of the principle of non-use of force or the threat of its use, as well as non-interference in internal affairs (Article 3);

- refusal to settle disputes by peaceful means (Article 4);

- breach of the principle not to support any action against the other party (Article 6);

- refusal to request immediate consultations in the event of a situation where one of the parties believes that its security has been (Article 7).

The agreements relating to the stationing in Crimea of the Russian Black Sea Fleet have been violated, inter alia, in the following terms:

- the maximum total number of military personnel, weapons and military equipment of the Black Sea Fleet permitted on Ukrainian territory (Article 4, paragraph 1 of the agreement ‘On the status of...’, and Article 7, points 2 and 3 of the agreement ‘On the parameters...’) – a violation occurred as a result of ferrying additional military formations from Russia into Crimea, including Mi-24 combat helicopters; Russia may keep 1987 soldiers in Crimea, totalling all land and air offensive units; Russia does not have the right to relocate combat helicopters onto the territory of Ukraine;

- actions respecting the sovereignty of Ukraine, observance of Ukraine’s laws and non-interference in Ukraine’s internal problems (Article 6, paragraph 1 of the agreement ‘On the status...’);

- organising training and related operational combat training activities within training centres, polygons, etc., in consultation with the competent authorities of Ukraine (Article 8, paragraph 1 of the agreement ‘On the status...’) – on 28 February, Russia announced that its actions in Crimea were part of pre-planned exercises;

- crossing the border, as well as the transportation of troops, weapons and military equipment, with regard to Ukrainian legislation on border control and customs (Article 13, paragraph 1, and Article 15, point 1 of the agreement ‘On the status...’).

Another, separate issue is the interaction of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation with the self-defence formations in Crimea, which, at least in the first days of the operation, may be regarded as an armed criminal organisation acting on the territory of Ukraine. After the de facto authorities of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (ARC) started creating their own armed forces (based on the self-defence forces), a problem of international law arose connected to the possibility of recognising the sovereignty of Crimea. The ARC army should in fact be treated the same way as other armed formations which are not recognised as state bodies, such as Transnistria (despite the lack of official recognition, the Transnistrian army participates in the implementation of multilateral agreements), even if the independence of Crimea has not been formally declared.

Conclusions and prospects

The Russians’ relatively smooth takeover of most of Crimea results, on one hand, from the good preparation of Russian troops to conduct this type of operation, and on the other, from the Ukrainian forces’ initial confusion (they probably did not receive the first clear orders to maintain their positions until 1 March). The units of the Russian army and the Crimean self-defence units gained the advantage over the remaining Ukrainian troops on the peninsula, and have maintained the initiative in achieving their objectives. The Russians’ complete mastery of Crimea – either through negotiation or by armed elimination of the blockaded Ukrainian units – should be considered as just a matter of time. In practice, this can only be stopped by a decision from Moscow to either change the operation’s objective or call a halt to it. No relief from the Ukrainian army units outside the peninsula should be expected, in connection with the build-up of sub-units of the Russian Armed Forces along the Russian-Ukrainian land border, and the continuing threat of Russian military intervention throughout the territory of Ukraine.

Map (large size)