Ukrainian-Russian war under the banner of anti-terrorist operation

In the last two weeks Ukrainian government forces have intensified their efforts to surround, and in the next stage retake, the main centres of separatist activities, namely Donetsk and Lugansk; and they have already achieved some local successes. Donetsk has been almost completely surrounded, but the Ukrainian forces have failed to take the most vulnerable of the towns around it and thus completely close the ring around the city. They face the obstacle of growing resistance from the separatists, who have been receiving more and more support from Russia, and of organisational and logistical problems with their own operations. Although there has been a noticeable drop-off in military action in the Donbas since the end of July, the initiative still remains with the government forces. Given the pivotal role of Moscow in maintaining and supporting the separatist forces, as well as the consistent nature of the armed clashes, employing a full range of heavy weapons, the anti-terrorist operation increasingly deserves to be called a Ukrainian-Russian war.

In connection with the early parliamentary elections planned for October, the government in Kyiv is aiming to bring an end to the hostilities in Donbas within the next few weeks. After the shooting down of the Malaysian plane, Ukraine received informal international permission to conduct a more robust military operation, and pressure from the EU on Kyiv to hold negotiations with the separatists ceased. However, it will be difficult to bring about a quick end to the fighting, for three main reasons. First, the government forces are not focused on cutting off the Russian separatists from their support lines and taking control of the border in the Lugansk region, which would be the priority from a military point of view. Second, even if Donetsk and Lugansk are cut off from the rest of the areas controlled by the separatists, it should be considered unlikely that the Ukrainian forces will be ordered to storm the two cities. Any tactical solution risks a humanitarian catastrophe of the like not seen in Europe since at least the time of the wars following the disintegration of Yugoslavia. Third, Russia is determined to prevent Kyiv from recovering full control over the Donbas, and Russian intervention under the pretext of humanitarian action is still possible. This means that the ongoing military operations in eastern Ukraine are likely to last a long time.

The course of the military actions

After the spectacular but militarily questionable success of retaking Sloviansk and Kramatorsk in early July, the offensive by government forces which had been launched in the second half of June was halted for a few days. The Ukrainian army’s activities were re-intensified by the shooting down on 17 July of the Malaysian passenger aircraft by separatists, which led to changes in the international perception of the conflict. Kyiv took advantage of a situation which favoured it to seize the initiative and recover some of its lost territory. On 19 July the new Minister of Defence of Ukraine, Valeriy Heletei, announced the continuation of combat operations aimed at surrounding Donetsk and Lugansk, and at destroying or displacing the separatist units from Ukraine.

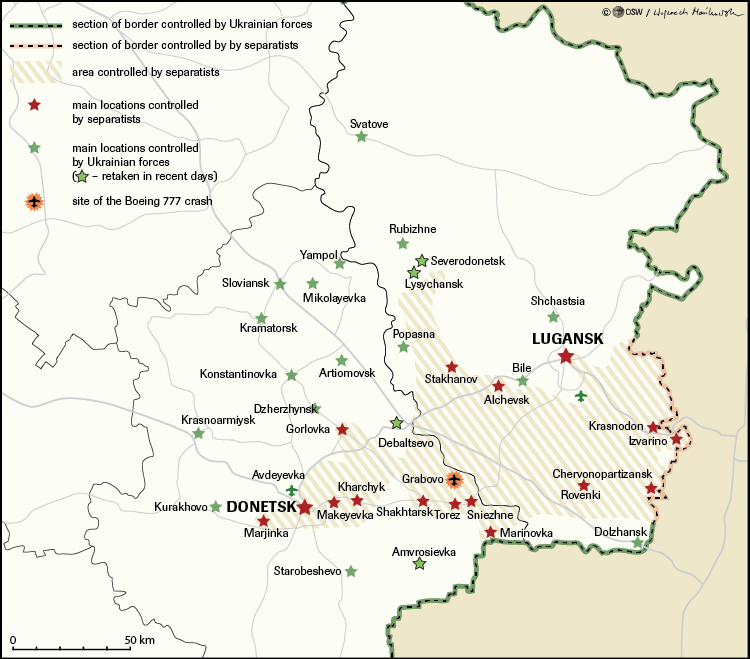

The Ukrainian offensive was initially focused in the north of the area controlled by the separatists, and its main targets were Lugansk, Severodonetsk and Lisichansk. Despite heavy fighting from 19 July, in which both sides started the full-scale use of heavy weapons (artillery, including ?multiple rocket launchers and armoured fighting vehicles; the Ukrainian side also attacked ground targets from the air), the Ukrainian troops failed to alter the situation in the area of Lugansk, and the separatists maintained their road links with Donetsk. On 24 July government forces retook Severodonetsk and Lisichansk, but their continued offensive in the area was halted, probably also because the focus of the fighting shifted to Donetsk.

On 25 July, a Ukrainian offensive began with the aim of retaking Gorlovka, Debaltsevo, Shakhtarsk, Torez and Sniezhne, cutting Donetsk off from the rest of the area dominated by separatists, and securing the region containing the remains of the downed Boeing. By 28 July, sub-units of government forces attacking from two directions had managed to push deep wedges into the separatists’ positions, retaking Debaltsevo and thus taking control of the main road connection from Lugansk to Donetsk. Despite several days of heavy fighting, however, the government forces failed to enter Gorlovka and Shakhtarsk.

The operations around Lugansk and Donetsk contrasted with the ‘trench warfare’ in the areas of the Lugansk region bordering Russia, where the government forces did not take any offensive action to regain control over the approximately 30-kilometre section of the border which is under the separatists’ control. This also resulted from the fact that Ukrainian troops were being systematically shelled from Russian territory (mainly from positions in the vicinity of Chervonopartizansk).

The evolution of the separatists’ tactics is noteworthy; in the event of stronger pushes from the Ukrainian forces, their sub-units have mostly retreated, destroying the road infrastructure as they withdraw, and preparing rings of defence around the larger cities (with particular emphasis on Donetsk). Since losing the road junction at Debaltsevo, the strategy has shifted towards the persistent defence of key towns (as reflected in the struggle for Gorlovka and Shakhtarsk). The separatists have also made serious attempts to recover the positions they have lost, and are being aided in this by a rising influx of technical materials from Russia. During the end of July and beginning of August, the separatists received what is probably the largest number of heavy weapons so far (including a minimum of 17 tanks).

Attempt to assess the situation

Compared with the government forces’ previous measures – in particular the clear impotence of the Ukrainian army which was observed during the spring – the operations carried out since the end of June (especially the offensive towards Lugansk and Donetsk in the last ten days of July) should be seen as a breakthrough. The government forces have taken the initiative, and as the separatists have maintained their current defensive posture, it remains with Kyiv. However, there has been no breakthrough in the strategic dimension – the only tangible result of the government forces’ current activities has been to regain control over part of its territory. The Ukrainian offensive has not only failed to deplete the separatists’ military potential, but has barely counteracted its systematic reinforcement at all. In a situation in which almost all the separatists’ equipment, an increasing number of the fighting troops on their side, and in fact their entire technical and material protection comes from Russia, the anti-terrorist operation increasingly deserves the name of a Ukrainian-Russian war. It no longer has the earlier character of limited guerrilla warfare, but now consists in fact of regular armed clashes between classic formations of land forces (equipped with artillery and armoured fighting vehicles), in which one party (Russia) is acting under the banner of the unrecognised Lugansk and Donetsk republics, while the other (Ukraine) is trying to maintain the legal appearance that it is not waging armed conflict with a neighbouring state in defence of its own territory.

The fact that Kyiv has de facto given up on the military priority of cutting off the separatists from their support from Russian territory raises the question of the Ukrainian forces’ real military ability to suppress the secession in eastern Ukraine, as well as what the political objectives of the anti-terrorist operation really are. It cannot be ruled out that the government forces – which should theoretically be able to restore control over the entire stretch of the border with Russia (even at the expense of a temporary suspension of their offensive action in other directions) – are not doing so for fear of direct, overt military intervention by Moscow. Cutting off the separatists from their military support in Russia would make their defeat just a matter of time, which would be unacceptable for Russia. Kyiv’s attitude may have been influenced by Russia’s systematic deployment along the border with Ukraine of more military units (as has been observed since the spring), the total number of which was estimated at 42,000 soldiers on 4 August. For comparison, the size of the separatists’ forces is estimated at 15,000, and the Ukrainian government forces engaged in the anti-terrorist operation (subordinate to the ministries of defence and home affairs) number 26,000 soldiers. Taking into account the Ukrainian forces being relieved and replaced, it means the involvement of almost half of Kyiv’s remaining military potential in the operation.

The limitation of the government forces’ aims should also be considered as arising out of their actual condition. Despite the apparent success of the government’s military forces, there are a range of organisational and logistical problems. One visible manifestation of the latter was the entry of a group of Ukrainian soldiers onto Russian territory; they may have been tired of the fighting, or running low on various materials (including ammunition and food). The most spectacular such incident came at the beginning of August, when a battalion of the 72nd Mechanised Brigade which had become cut off from the rest of its group crossed the Russian border; in the first days of August, there were a total of nearly 500 Ukrainian soldiers and border police officers on Russian territory, 180 of whom decided to return to Ukraine. There are also increasing numbers of injured Ukrainian military personnel being treated in Russian hospitals. It cannot be ruled out that if such trends continue, the Ukrainian offensive carried out in the last ten days of July will remain the greatest success of the entire anti-terrorist operation.

Prospects

After the successes of the military operation in Donbas which have been observed in recent weeks, the authorities in Kyiv have begun optimistically declaring that they will end up regaining full control over the region within a few more weeks. President Petro Poroshenko, as commander in chief under the Constitution, is seeking to lead the operation to final victory before the parliamentary elections planned for October, which would not only allow them to be held in the east of the country, but would also contribute to electoral victory for his Solidarity party. The public’s increasing weariness at the protracted military activities carries a risk for Poroshenko that his popularity may rapidly decline over the next few months. In addition, the deepening economic crisis in Ukraine, another embargo on Ukrainian exports by Russia, and the lack of supplies of Russian gas will affect the worsening mood of Ukrainian society.

Kyiv’s efforts to bring a swift conclusion to the war in the Donbas stand in contrast with the objectives of Russia, whose activities are aimed at maintaining the destabilisation in eastern Ukraine for as long as possible. The Russian authorities still hope that they will be able to use their instrumental control of the Donbas to influence Kyiv politically. Moscow is also ready to trigger a humanitarian disaster in the region, where there are already systematic problems with supplies of water and electricity and keeping stores stocking, thereby increasing the waves of refugees, whose number is currently estimated at over 300,000 people (including those who have left for other regions of Ukraine and Russia). Russian diplomacy is increasingly aggressive in accusing Kyiv of causing a humanitarian disaster. By introducing sanctions worsening Ukraine’s economic situation, and by fuelling political conflict, these moves also serve to delegitimise the Ukrainian government under President Poroshenko.

As a result, Russian military aid to the Donbas (weapons and soldiers, including from units of the Russian army) is expected to increase in the coming weeks. This will extend the actual state of the Ukrainian-Russian war in the east of Ukraine, and deepen the problems and challenges facing Kyiv. If it turns out that Ukrainian forces are close to regaining control over the region, regular Russian army troops might be introduced under the pretexts of a peacekeeping operation and preventing a humanitarian disaster. At that point, the Ukrainian-Russian war would enter a phase whose consequences would be incalculable.

Map