A strong vote for reform: Ukraine after the parliamentary elections

On 26 October, Ukraine held early parliamentary elections, which were won jointly by the Popular Front of Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk and the President’s eponymous Petro Poroshenko Bloc. The Verkhovna Rada (parliament) will also consist of representatives of the Self-Help, Opposition Bloc (who are mainly former members of the Party of Regions), Radical and Batkyvchina parties. Svoboda failed to cross the 5-percent electoral threshold. This electoral result is a decisive victory for forces advocating the pro-Western orientation of Ukraine and reforms to its economy and social life. After the new Parliament is convened (probably in the second half of November) the formation of a coalition is to be expected, consisting of at least three parties (the Poroshenko Bloc, the Popular Front and Self-Help). Most likely, Arseniy Yatsenyuk will remain as head of the new government, as since the elections his position has strengthened significantly due to the unexpectedly high electoral result for the Popular Front, and the much lower than expected result for the Poroshenko Bloc.

The election results

The elections were held in two forms: as a proportional vote on national electoral lists (for the political parties, and not for specific representatives), as well as voting in single-member constituencies (in which a plurality of votes was sufficient for victory). In the proportional vote, 225 deputies were chosen; and in the single-member constituencies 198, instead of 225, as elections were not held in the 12 constituencies of Crimea and 15 constituencies (out of 24) of the Donetsk and Lugansk regions.

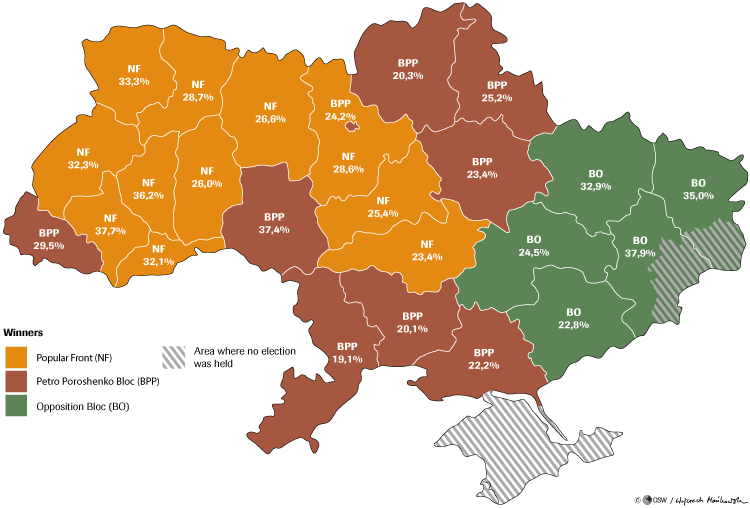

According to unofficial results released by the Central Electoral Commission, in the proportional elections first place was taken by the Popular Front (22.17% of valid votes). The Petro Poroshenko Bloc (21.82%) ran only slightly behind. The next places were occupied by Self-Help (11%), the Opposition Bloc (9.36%), the Oleh Lashko Radical Party (7.44%) and Batkivshchyna (5.68%). The victors in the individual regions are shown on Map 1.

The following parties failed to pass the 5-percent electoral threshold: Svoboda (4.72%), the Communist Party of Ukraine (3.86%), Civic Position (3.11%) and Strong Ukraine (3.09%). None of the other parties gained more than 3% of the vote (Right Sector was supported by 1.81% of voters); 22% of the votes went to these parties. Some of them gained seats in single-member constituencies. These figures come from 98% of the voting districts; the missing numbers from those electoral committees which saw irregularities in determining the outcome of the elections cannot significantly change the results.

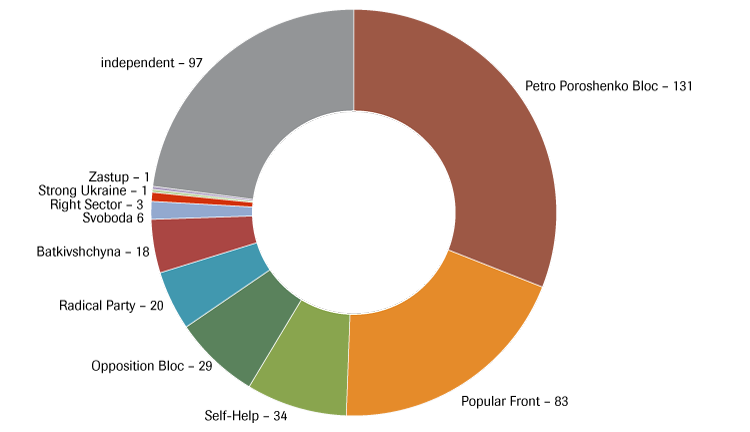

According to preliminary calculations of the proportional and majority voting, the Petro Poroshenko Bloc has won a total of 131 seats, the Popular Front 83, Self-Help 34, the Opposition Bloc 29, Lashko’s Radical Party 20, Batkivshchyna 18, Svoboda 6, Right Sector 3, and Strong Ukraine and the little-known Zastup party, one each (see diagram in Appendix). The remaining 97 deputies elected in single-member constituencies are not formally associated with any major party; many of them are representatives of the bureaucracy and business. After the constitution of the parliament, a substantial portion of these will join other factions, primarily the Poroshenko Bloc and the Opposition Bloc. This will probably ensure the coalition of the Poroshenko Bloc and the Popular Front a simple parliamentary majority (226 votes).

The turnout

30.45 million inhabitants of Ukraine and 0.5 million in the ‘foreign voting district’ were entitled to vote. Voter turnout (calculated without the ‘foreign district’) was 52.4% on average, ranging from 70% in the Lviv region to 32.4% in the part of the Donetsk region controlled by Kyiv (see Map 2). Turnout was therefore lower than in May’s presidential election (60.3%), which was also not held in Crimea and parts of Donbas, and also slightly lower than in the parliamentary elections of 2012 (57.9%), which were held across the country.

This figure was determined after the Central Electoral Commission deducted the eligible voters included on the National Register of Electors (as of 1 September 2014) as inhabitants of Crimea as well as those constituencies in the Donetsk and Lugansk regions where the conduct of elections was abandoned. According to the register, the number of voters is 1.8 million in Crimea, 3.3 million in Donetsk and 1.8 million in Lugansk. Meanwhile, according to the CEC, the number of those entitled to vote in the ‘active’ districts of the Donetsk region was set at 1.4 million, and 500,000 in Lugansk; these numbers were the basis for calculating the total turnout. After converting the data on the number of voters in relation to the whole number of voters, turnout in the Donetsk region therefore comes to 15.2%, and in the Lugansk region 8.3%. Accordingly, the turnout for all the ‘mainland’ of Ukraine (without Crimea) is reduced to 46.7%.

The low turnout in the Donbas is due to several factors: the most densely populated part of the region is under the control of the separatists, while in the rest of the area, a large part of the population felt intimidated and did not see any political force which it could support. This is also partly a consequence of the previous authorities, whose roots lay in that region, artificially increasing voter turnout in the Donbas in the previous election.

The conduct of the elections

The elections corresponded to democratic standards, as confirmed by the first assessments by the international observer missions, including the OSCE (the CEC registered 2300 observers from foreign states and international organisations, including 112 from Poland; there were no representatives from the Russian Federation or other CIS countries). Polling could not be carried out in some parts of Donetsk and Lugansk regions controlled by government forces. However, incidents both during the voting and the counts were numerous, and the technical and organisational level was lower than in previous elections, because of the poor training of the personnel and the fact that the state structures were generally functioning worse. Yet despite fears, there were no terrorist attacks or attempts to prevent voting (except in one case where separatists fired at a polling station on the border of the zone controlled by government forces), and around a dozen false bomb scares at polling stations.

These irregularities did not affect the outcome of the election with regard to the proportional vote, however, they could have had an impact in some single-member constituencies. The uncertainties related to the voting and the counts in these constituencies are likely to be the subject of formal complaints.

Winners and losers

The pre-election polls showed a clear victory for the Poroshenko Bloc, second place for the Oleh Lashko Radical Party, a good result for Batkivshchyna, reasonable outcomes for the Popular Front and Civic Position, and a chance of crossing the electoral threshold for Self-Help and the Opposition Bloc; Serhiy Tihipko’s Strong Ukraine, another project aimed at former voters of the Party of Regions, also seemed to have a better chance. Although the percentage of undecided voters was very high until the last minute, such serious discrepancies between the polls from mid-October and the actual election results call into question the reliability of the Ukrainian public opinion research centres.

The winner of the proportional vote unexpectedly turned out to be the People’s Front, led by Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk and the speaker of parliament Oleksandr Turchynov. In fact, the vote is mostly an expression of support for Yatsenyuk and represents a personal success for him. It is also a sign of the support by a large part of the electorate for a firm policy against the insurgency in the Donbas and the Russian aggression. Yatsenyuk and Turchynov are considered the leaders of the ‘war party’, whereas Poroshenko is seen to be the leader of the ‘peace party’. On the other hand, most voters treated the Bloc and the Front as allied parties, which are not competing with each other. The Popular Front is a new party, which was created after a breakaway of some leading Batkivshchyna politicians from Yulia Tymoshenko. Its electoral success testifies to the fact that the group was able to take away from Batkivshchyna not only a significant part of its electorate, but its party structures as well. However, the Front is still not a fully formed, national political party.

Formally the Petro Poroshenko Bloc is the joint victor of the proportional elections, and a large number of deputies from single-mandate constituencies will make it the biggest party in parliament, but nevertheless the result represents a certain kind of failure. Poroshenko had been counting on support from approximately 30-40% of the electorate, and on dominating the parliament. In the new situation, further cooperation with Yatsenyuk and entrusting him once again with the premiership is not a question of choice, but a political necessity. This result for the Bloc reflects decreased public confidence in the president, which is linked to the slow pace of reforms, especially the fight against corruption, as well as the failure of the anti-terrorist operations in the summer, and the lack of support from a large part of the population for peace talks with the militants and Russia. The Bloc (which in fact is a party called a ‘bloc’, as the formation of electoral blocs is prohibited in Ukraine) is also an organisation in the process of taking shape, and its base was made up of the party structures of UDAR, the future of which is uncertain; it may be formally included in Poroshenko’s party.

The third place result for Self-Help is the biggest sensation of the election. This party, which was founded at the end of 2012 by Andriy Sadovy, the mayor of Lviv (based on an association which had existed since 2004) is the only major Christian-democratic grouping in Ukraine. A key element of its programme is strengthening local government. The party, which was initially a local initiative in 2014, began to grow rapidly in cities all over the country, especially Kyiv, where in the May city council elections it won 7% of the vote, and almost 19% in the latest elections. Self-Help’s programme is aimed primarily at young people with democratic-liberal views. Its chances of expanding its support outside the metropolitan centres seem to be limited. Outside Lviv, Self-help is only now beginning to expand its structures. It is the only party which did not have any former parliamentarians or any individuals connected to oligarchic groups on its lists. Its candidates were mainly recruited from community NGOs and mid-size businesses. It is worth noting that the party leader decided not to fight for a parliamentary seat, but rather to remain mayor of Lviv, and so he put his name fiftieth on the party list (the party could not count on winning that number of seats). This attitude contrasts with the decision taken by Vitaliy Klitschko who, despite leading the Poroshenko Bloc’s list, openly declared his intention not to return to parliament. This could have drawn votes to Self-Help, and away from the Poroshenko Bloc.

The success of the Opposition Bloc, although unexpected in the light of the opinion polls, should not come as a surprise. An electorate which is unenthusiastic about the changes taking place in Kyiv, albeit not necessarily as pro-Russian as a year ago, is still abundant in the south and east of the country. The fact that the Party of Regions did not join the Bloc, and the most discredited politicians from the Yanukovych clique were not on its list, allowed it to find some voters who did not like either the new or the old authorities. The strength of the Bloc turned out to be the support it received from some oligarchs, especially Rinat Akhmetov, and also (in all likelihood) its acquisition of a substantial part of the organisational structures of the Party of Regions. The Bloc managed to push off the electoral stage both Strong Ukraine, the competing ‘post-Regional’ project led by Serhiy Tihipko, as well as the Communists, who for the first time have no seats in parliament, and will now descend to the margins of political life. The Opposition Bloc is only now taking shape as a viable political structure.

The Oleh Lashko Radical Party has entered parliament, but its result turned out to be much poorer than expected; the demand for radical populism among Ukrainian voters turned out to have been overestimated. The party also failed to push Batkivshchyna out of parliament (although they deprived Tymoshenko of a large part of her support in rural areas and small towns). This party has also failed to become a national political structure. Some of its deputies are associated with the former head of the Presidential Administration Serhiy Lovochkin, who is believed to be secretly funding the party (even though Lovochkin himself entered parliament on the Opposition Bloc’s list).

Batkivshchyna is decidedly the election’s biggest loser, barely clearing the electoral threshold. In the course of the campaign the party lost a large part of its personnel and structures. Basing its strategy on the popularity of Yulia Tymoshenko was a huge mistake (Nadiya Savchenko, the pilot captured by the Russians, was first on the party list, but she was only a symbol, and Tymoshenko was the real ‘face’ of the campaign). This failure marks the beginning of the end for Batkivshchyna.

Svoboda also suffered defeat; it did not pass the electoral threshold and lost in a number of single-member constituencies (including all of them in the Lviv region). It will have six deputies in the new parliament, none of whom belong to the party’s leadership. This disaster is a consequence of both the mistakes made by Svoboda during the ‘Revolution of Dignity’, and is also a negative assessment of the activities of the local authorities it has controlled in western Ukraine. Another factor undermining Svoboda was the fact that during these elections radically patriotic, anti-communist and anti-Russian language was used by all the parties except the Opposition Bloc, and they proved to be more attractive to voters for other reasons.

A renewed parliament

The new parliament will see a decided advantage for pro-European parties (which is all of them except the Opposition Bloc and radicals), who will be ready to cooperate either formally or informally. Anti-European and pro-Russian groupings will form a small minority (although the Opposition Bloc, reinforced by ‘single-mandate’ deputies, may be the third biggest party). However, it is important that they have entered parliament because they represent a significant part of the population, with which the current ruling camp must seek agreement. The presence of this bloc in parliament may reduce the tension in the east and south of the country, although on the other hand it will consolidate the pro-European coalition.

Most of the deputies – perhaps over 250 of them – will be in the Parliament for the first time; a certain part of them will have had experience in regional government. Among the dozens of deputies who have previously sat in parliament, a large part of them are in the Opposition Bloc. In the pro-European ranks new people will predominate: social activists, small and medium entrepreneurs, and also a group of journalists and officers and soldiers from volunteer battalions. Many of them are thoroughly educated, but they lack political experience. We may expect this group to give active support to reforming the country, especially in the fight against corruption.

There will probably be around twenty members of volunteer battalions, who will be found in all the parties except the Opposition Bloc and the Poroshenko Bloc. Their presence in parliament will make it easier to involve the volunteer military formations, which represent a potential danger to the stability of the country, in the political process.

The parliament will also include numerous representatives of the oligarchs, especially Ihor Kolomoyski (mainly in the Poroshenko Bloc), Dmytro Firtash and Serhiy Lovochkin (mainly in the Poroshenko Bloc, Lashko’s party, and the Opposition Bloc), and Rinat Akhmetov (mostly in the Opposition Bloc). There will be, however, far fewer of them than in previous parliaments, and their influence will be weaker (except for Kolomoyski, who previously had been poorly represented in parliament).

Outlook

Taking into account the likely number of factions in the new parliament, the creation of a government will only be possible with a coalition between the Poroshenko Bloc and the Popular Front, and in this situation Yatsenyuk will remain prime minister. The establishment of such a coalition was being prepared even before the elections. The results, however, have considerably strengthened Yatsenyuk’s position, and the first actions of the president and prime minister since the elections indicate that setting the final terms for the coalition may not be easy.

It is likely that Self-Help will be co-opted into the coalition, and it will probably impose conditions which are difficult for the current government to accept (such as forming a government based not on quotas, but according to individual ministers’ qualifications). In contrast, the chances of creating a supermajority of 300 votes to permit amendments to the constitution seem small without the support of Batkivshchyna. If such a majority cannot be found, only such reforms that do not require changes to the constitution will be possible. However, we may anticipate that these reforms will be passed fairly smoothly and quickly.

The fact that no one party has a definite advantage has led some observers to predict a rapid conflict between Poroshenko and Yatsenyuk, similar to that which occurred between Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko in 2005. These fears seem exaggerated, however: one of the sources of that conflict was the abandonment of early parliamentary elections, and the current situation in Ukraine is much more difficult than in 2005, which its leaders (and the participants of the 2005 conflict) are fully aware of. In particular, the external threat from Russia and the continuing revolutionary upheaval in the country should motivate Ukraine’s political leaders to maintain the unity of the reform camp.

Appendix

The balance of forces in parliament

Winners in the regions

Voter turnout in the regions