Disappointment and fear – the public mood in Ukraine

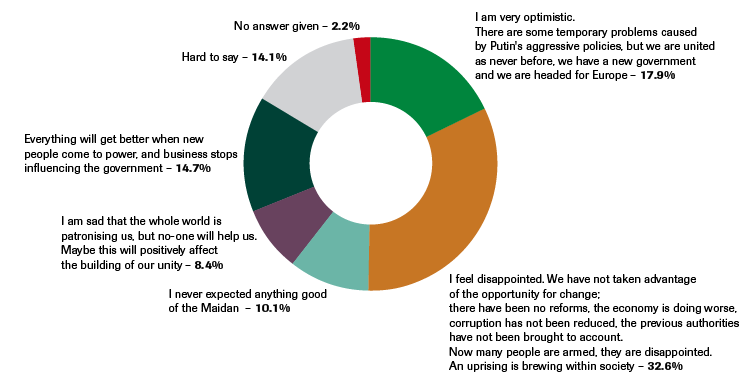

Towards the end of 2014, two recognised sociological institutes in Kyiv, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) and the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DI), conducted extensive research on the public mood in Ukraine. Their results indicate growing public disappointment at the state of the nation and the actions taken by the new government. In the general opinion, apart from Ukraine’s image on the international arena improving and the introduction of a clear foreign policy aimed at rapprochement with the EU, Ukraine's situation has deteriorated in all other areas of the state’s action. The KIIS’s research, conducted a year after the outbreak of the Euromaidan, confirms that for a large part of the Ukrainian public, the anti-government protests have turned out to be a missed opportunity to make a qualitative change in the state. The biggest disappointment among respondents has been caused by the lack of reforms, the unsuccessful fight against corruption, the deterioration of the economic situation in the country, and the lack of accountability for the people involved in repressing the opposition and suppressing the Euromaidan. It is important that for this part of the population, the situation threatens the outburst of another wave of protests, public readiness to participate in which remains at a high level.

Changes for the worse

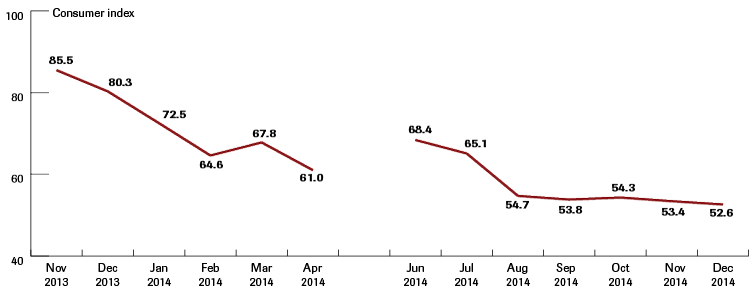

In Ukraine, disillusionment caused by the lack of reforms and the worsening economic situation is rising; up to 94.2% of those surveyed by DI said that Ukraine's economy is in much worse shape than last year. At the same time, the deepening crisis is being increasingly felt by society; 84.3% of respondents said that their material wellbeing had deteriorated. These sentiments result from the devaluation of the hryvnia (which over the year has lost half of its value), price increases, the systematic rises in municipal fees, as well as temporary power cuts in late November and early December. All of these factors have led to a drop in the standard of living in Ukraine which the general public feels keenly. According to data from another research group, GFK Ukraine, which since 2000 has regularly published monthly reports on the public consumption index (an opinion of the financial situation and the country’s economy), in November 2014 this had reached the lowest level since the crisis of 2008.

The vast majority of Ukrainians do not see any qualitative changes in the country. In their view, most of the pressing problems remained at the same level as before the Euromaidan, or have even deepened. According to the DI study, up to 60% of respondents believed that crime levels have risen in Ukraine, which is confirmed by statistics published by the General Prosecutor of Ukraine; in comparison with 2013 many times more serious crimes have been committed, and many more burglaries and acts of violence against small and medium-sized businesses have been committed. In addition to the increase in insecurity, Ukrainians feel disappointment with regard to the state apparatus; 42.8% of respondents said that over the last year, officials have proved themselves even less likely to stick to the letter of the law when taking decisions. In addition, for 49.5% of the poll’s participants, the authorities’ approach to the citizens has changed for the worse.

The benchmark of the changes for the majority of Ukrainians is the state of the fight against corruption. However, this burning question for Ukraine is still more in the realm of discussion and political promises than that of real action. Meanwhile, according to the KIIS research, for 46.8% of respondents one of the main objectives of the Euromaidan was to destroy the networks of corruption in the country. However, a year later, 47.3% of the population believes that corruption has remained at the same level, and 31.8% say it has increased. Only 4.8% of respondents say there has been an improvement in this area.

The crisis of confidence in politicians and public institutions

Those mainly responsible for the current state of affairs, according to the respondents, are the politicians, as is reflected in the results of the DI poll. The level of trust in the politicians associated with the ruling parties remains low. Particularly low levels of public trust are held inter alia by Yulia Tymoshenko (whom 75.2% of respondents do not trust); Oleksandr Turchynov, the Secretary of the National Security and Defence Council (62.2%); Arsen Avakov, the Interior Minister (61.6%); Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv (58.8%); and Andriy Parubiy, the former commander of the Maidan Self-Defence, and currently Vice-President of parliament (51.1%). People who enjoy the trust of society include President Petro Poroshenko (50.5% of respondents trust him), and Andriy Sadovyy, the mayor of Lviv, and leader of the Self-Reliance party (43.6%).

Despite the rise to power of politicians associated with the opposition, a crisis of confidence in public institutions is continuing in Ukraine. A clear majority of the population does not trust the parliament (56.9% of respondents), the government (54.2%) or local government (51.8%). Particularly low ratings of trust are shown to the authorities responsible for maintaining law and order; 80.6% of respondents do not trust the courts, 75.2% do not trust the prosecution, and 74.2% do not trust the police. The only institutions that are trusted by most of the population are the Orthodox church (64.5% of respondents), the army (57.9%) and the Ukrainian media (51.8%).

Reforms called into question

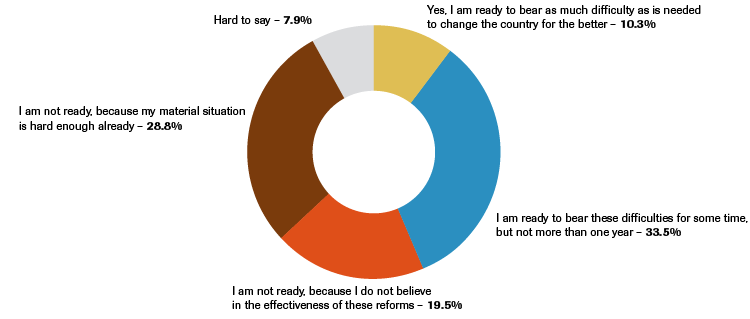

One of the main sources of the persistent low levels of trust in public institutions and the political class is their unwillingness to make structural changes. At the same time, the excessive and demanding public expectations with respect to reforms are disturbing, as is the failure of the majority of Ukrainians to understand the costs of such changes. To a great extent, this is the result of insufficient communication between the public and the authorities, who have discussed some of the reforms only in populist slogans, and who have introduced other changes in an opaque manner. In the DI poll, only 10.3% of respondents said they were willing to make sacrifices for more than a year. At the same time, 33.5% of the respondents stated that they would make allowances for temporary problems lasting a period of one year. 28.8% of respondents said they were not ready to make sacrifices because of their financial problems. At the same time, an additional 19.5% were against bearing the costs for the reforms, due to a lack of faith in their effectiveness.

As a result, a large part of Ukraine’s citizens still believe that the changes in the country should primarily concern increased spending by the state (increases in pensions, early retirement, investments in healthcare), and increased opportunities to prosecute politicians and officials for their transgressions (by depriving them of their legal immunity). Public confidence in the government has been undermined by the fact that so far no one has been held responsible for the suppression of anti-government protests on the Maidan, or for supporting separatism in the country; nearly 75% of respondents believe that this is the result of incompetence or deliberate actions by the new Ukrainian authorities.

The mood in the regions

Residents of south-eastern Ukraine are particularly reluctant to bear the costs of the reforms; a clear majority of these people have remained passive in the face of the protests in Kyiv. They were only motivated by the conflict in the Donbas, preceded by the annexation of Crimea. Above all, the deterioration of the situation in the Donetsk and Lugansk oblasts has increased the combat readiness of the inhabitants of other regions which are at potential risk of separatism. In the case of the Dnepropetrovsk, Zaporozhe, Nikolayev, Odessa and Kherson regions, over the last six months an average of 25% more respondents (up to c. 50% in total) have declared themselves ready to engage in armed resistance against external aggressors (if the conflict spills beyond the Donbas). Their main motivation was to defend their families and relatives (50.5% of respondents) and their property (18.7%).

Thus, the threat of separatism and the outbreak of hostilities in the region has effectively strengthened the sense of the south-eastern regions’ loyalty to Kyiv. At the same time, it is in the south where the highest number of respondents dissatisfied with the situation in the country can be found one year after the Euromaidan, where as much as 46.8% of those interviewed by the KIIS expressed their dissatisfaction, and only 11.7% positively rated the changes and the chances of recovery. In these regions, which had been opposed to or were passive regarding the Euromaidan, to the deterioration of the economic situation and the possible costs of reform would strike especially hard. As a result, there may be a return of support for politicians formerly associated with the Party of Regions. It should be noted, however, that in the light of a number of sociological studies conducted over the past year, all kinds of support for clear separatist tendencies and federalisation in south-eastern Ukraine have decreased; any possible social discontent will therefore be targeted primarily at the present authorities, and not at the Ukrainian state as such.

Outlook

It is clear that in Ukrainian society frustration at the inertia of the current government is growing, which in turn could lead to a new outbreak of social unrest. The critical points, which may result in an outburst of protests, will be a lack of reforms, their slow pace and – paradoxically – the extra costs associated with them. At this time, a factor restraining any protests is the ongoing conflict in Donbas, who 79.4% of Ukrainians considered one of the five biggest problems that Ukraine must resolve in the near future. As long as the war lasts, the authorities can count on more patience and understanding from the general public. However, in case of further inaction in the fight against corruption, in judging those guilty for the victims during the Euromaidan, and subsequent increases in municipal fees and prices, we may expect more and faster rises in discontent, and in the willingness of Ukrainians to join active protests, despite the ongoing conflict.

Appendix

1) Charts

Evaluation of your own material situation and the country’s economic situation

(consumer sentiment index; see section 2, Research methodology)

Source: GFK Ukraine

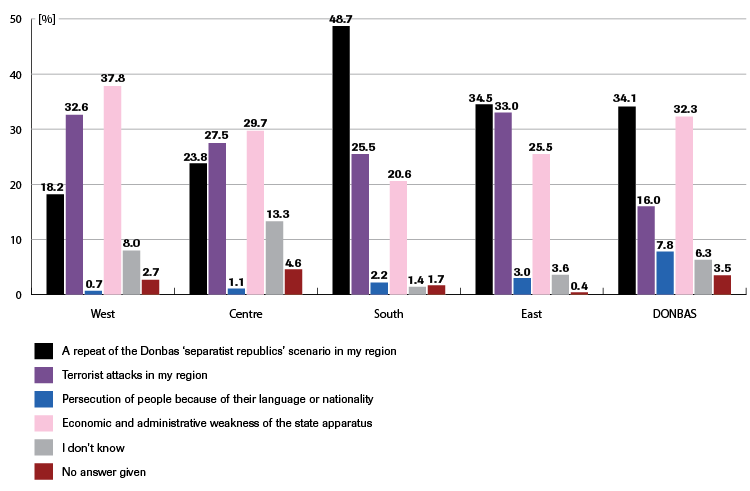

What are you most afraid of?

(one response only)

Source: Kyiv International Institute of Sociology

Are you ready to bear the costs of introducing reforms?

Source: Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiative Foundation

Evaluating the situation in Ukraine one year after the Euromaidan

Source: Kyiv International Institute of Sociology

2) Research methodology

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology

The poll was conducted on 6-17 December 2014 on a sample of 3065 people aged over 18 in all regions of Ukraine. In the case of Donetsk and Lugansk regions, testing took place only in areas under the control of the Ukrainian authorities, and partly in Donetsk. Respondents were asked different variants of the questions; in some, the answer had to be given by selecting one option, and in others the respondent could choose more than one answer. Some of the results were broken down by individual regions of Ukraine: West, Central, South, East, Donbas (Donetsk and Lugansk regions). The research was funded by the governor of Donetsk, the oligarch Sergei Taruta; the results were published in Dzerkalo Tyzhnia.

Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation

The study was conducted on 19-24 December 2014 on a sample of 2008 people aged over 18 in all regions of Ukraine (except the annexed Crimean peninsula). The margin of error is 2.3%. The study was conducted jointly with the Razumkov Centre. To determine the type of trends and the changes in public sentiment from 2014, the results were compared with those taken 2013, carried out on the same days (19-24 December) by the same research centres (DI and the Razumkov Center). Respondents were asked different variants of the questions; in some, the answer had to be given by selecting one option, and in others the respondent could choose more than one answer. The results were not broken down by region, age, or education, and were only given on a country-wide basis. Financial support for the project was guaranteed by the Dutch embassy.

GFK Ukraine

The consumer sentiment index is a monthly survey conducted by GFK Ukraine since June of 2000. Since January 2009, the results of the research have been published monthly. They are based on answers to five questions: ‘How has the state of your family's assets changed in the past six months?’; ‘What do you think your family's financial situation will look like in six months?’; ‘Will the country's economy improve or weaken over the next six months?’; ‘In five years will the situation in the country have improved or deteriorated?’; ‘Is now a good or bad time for large domestic purchases?’. The results are given on a scale of 0 to 200, where 200 is a completely positive attitude, 100 represents the same number of positive and negative responses, and results below 100 denote a negative response.