Turkey’s Syria policy in crisis

At the end of June, the Turkish government signalled the possibility of conducting a military intervention in northern Syria, to halt the expansion of the Kurds associated with the Democratic Union Party (PYD, the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers Party), and of Islamic State (IS).

These signals are a reaction to the evolution of the Syrian war, which is progressing unfavourably from Ankara’s point of view. Turkey’s strategic objective, which is the overthrow of the regime of Bashar al-Assad, now seems unrealistic. The regional position of the Kurds, whom Ankara sees as its enemies, has now clearly strengthened, and the threat from Islamic State is also rising. The conflicts south of Turkey’s border are increasingly affecting its security situation, its domestic and foreign policies. Turkey remains helpless in the face of these challenges.

It is doubtful that Ankara will decide on wide-ranging military intervention in northern Syria because of the excessive risks of such an operation. Its signs of readiness to use the army are more likely to be a threat aimed at the Syrian Kurds and Islamic State. They may also be a demonstration on the domestic scene that the Justice and Development Party, which has been weakened since June’s parliamentary elections, still retains control over politics and national security.

The evolution of the Syrian war in the eyes of Ankara

The situation in Syria is developing unfavourably for Turkey. Firstly, the main goal of Turkey – the stabilisation of the country by overthrowing the Assad regime – is unrealistic. Attempts to persuade the United States to extend the anti-terrorist campaign in Syria and Iraq to fighting Assad’s forces have failed. Branches of the anti-government opposition (mainly the Free Syrian Army) which have received logistic, training and weaponry backing from Ankara are being superseded on the battlefield by the forces of the regime, the Kurds, other Islamic State and others, and are thus being consistently driven out of northern Syria.

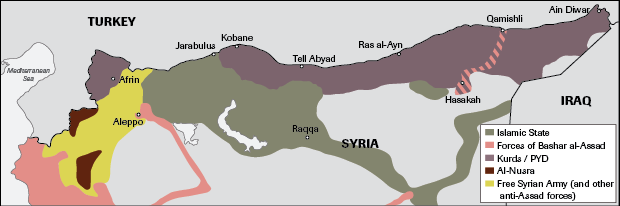

Secondly, in recent months there has been a significant strengthening of the position of the Kurds associated with the PYD in Syria. Starting from March this year, they have managed to oust Islamic State militants from many northern areas of the country (Kobane, Tall Abyad and Hasaka, the latter together with the Assad regime’s forces). In this way they have linked a series of territories which had previously been separated from each other, and taken control of the 400-kilometre strip along the border with Turkey, including the border crossing points. From Ankara’s point of view, the strengthening of the PYD poses a serious geopolitical challenge. According to the Turkish authorities, this process is also being accompanied by the displacement of the local Arab and Turkmen populations, which is intended to perpetuate the Kurdish dominance (and boosts the waves of refugees entering Turkey). Despite Ankara’s protests, the US’s informal tactical alliance with the Kurds is being boosted. The Turkish government maintains that the PYD’s series of victories over Islamic State would not have been possible without the support of the US Air Force. Ankara fears that the PYD will attempt to further its territorial expansion by trying to connect the areas in north-eastern Syria in controls with areas to the north-west, such as the areas surrounding the city of Afrin, which are separated by territories currently controlled by Islamic State and other rebel groups (including Al-Nusra, which is associated with al-Qaeda, and the Free Syrian Army).

Thirdly, the strengthening of Islamic State represents a growing problem. Initially Ankara had hoped to be able to manipulate the armed jihadist organisations, or at least come to a peaceful coexistence with them. Turkey’s hopes that the jihadists would contribute to the defeat of Assad, or prevent the expansion of the Kurds in northern Syria, have not been fulfilled. The establishment of IS as a regional actor, despite air strikes since last August by a coalition led by the United States, and its defeats in battles with the PYD, poses a growing threat to Ankara. Islamic State is the main source of the destabilisation of the Turkish neighbourhood, as it participates in almost all the battles in the border regions, with the Kurds, Assad’s forces, the Free Syrian Army and other groups. The consequences of the strengthening of IS are also being increasingly felt inside Turkey. Before IS’s expansion successive waves of refugees had fled to Turkey (around 2 million Syrian refugees are currently resident there). The penetration of jihadists onto Turkish territory threatens its internal security, and undermines the country’s international image and its ties with the West as the media and many foreign partners suspect that Turkey is tolerating IS’s presence there, and that it is encouraging the jihadis in their battles against the Kurds.

Domestic conditions

The socio-political situation in Turkey limits Ankara’s room for manoeuvre in its policy towards its southern neighbourhood. It is also becoming increasingly associated with the processes taking place in Syria.

First of all, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been weakened on the domestic scene since losing its ability to form a government after the June parliamentary elections. Foreign policy is likely to be subordinated to the needs to create a coalition government, and in the event of early elections, it will be judged by an electorate which does not want Turkey to get involved in the Syrian war.

Secondly, the attempts to undermine de facto Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria have met with increasingly harsh resistance from the Kurdish population in Turkey. A clear manifestation of this was the violent clashes between Turkish Kurds and the police and army which broke out last October in connection with the Turkish isolation of the Kurdish town of Kobane, which was being attacked by Islamic State. In addition, the electoral success of the Kurdish Democratic People’s Party (HDP) in June’s parliamentary elections in Turkey has strengthened the position (and the assertiveness) of the Kurds on the Turkish political scene.

Thirdly, in its policy towards Syria, Ankara is increasingly obliged to take into account the risk of confrontation with Islamic State militants, who have easy access to the territory of Turkey via the porous Turkish-Syrian border. In addition, more and more Turkish citizens are joining the ranks of IS; estimates put the number of Turks participating in jihad in Syria and Iraq at several thousands.

Military intervention as a chance to take the initiative?

On 14 June, commenting on the strengthening of the PYD in northern Syria, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said that Turkey will not allow the creation of a new state there. According to press reports, at the end of the month the government ordered the army to plan for different variants of military intervention in northern Syria. The army apparently declared its willingness to follow orders, but at the same time it tried to discourage the government from carrying out intervention, due to the high risk of their own losses, as well as likely opposition from Turkey’s allies and foreign partners; and it also suggested suspending the decision to initiate a military operation until a new government has been formed. On 29 June, after an emergency meeting of the National Security Council, the government announced the possibility of creating a buffer zone in northern Syria, of 100 km in length and around 33 km in depth. At the same time the Turkish Air Force was put on a state of heightened alert, and tanks and heavy military equipment began to assemble on the borders with Syria. According to press reports, the buffer zone could be created in the area where IS is fighting the anti-Assad rebels (mainly the Free Syrian Army), between the Kurdish-controlled towns of Kobane and Afrin. Creating the buffer zone would involve supporting the Free Syrian Army by shelling IS positions, and possibly those of the Kurds (if they entered the area), the deployment of air support, and – in the extreme scenario, if necessary – the intervention of Turkish land forces.

It is difficult to give an unambiguous interpretation of Turkey’s signals of its intention to carry out military intervention. Such a scenario could give Ankara a chance to take the initiative in the conflict in northern Syria, and to halt the expansion of the Kurds and Islamic State. This could also strengthen the anti-Assad rebels supported by Ankara. A military intervention could also be a factor in the AKP’s calculations to consolidate the electorate before possible early elections, which would help it obtain a majority and form a government.

However, all of the factors that have determined Ankara’s lack of direct involvement in the armed struggle in Syria so far still militate against any intervention: the fear of large losses of its own troops, and of getting entangled in the conflict without a clear perspective of a strategic goal (removing the Assad regime, stabilising the country); public resistance to getting involved in the Syrian war; the prospect of internal conflict with the Kurds; the risk of open confrontation with IS; the high risk of tensions with external actors, including Iran and Russia, but also the USA.

Conclusions

Turkey’s Syria policy is currently in crisis. So far, Ankara has failed to have any significant influence on the course of events or the alignment of forces in the conflict zones. On the contrary; Assad’s regime has defended itself effectively, the Kurds have significantly strengthened their position; and the threat from Islamic state seems to be rising. The domestic situation, including the weakening of the AKP’s position since the June parliamentary elections, further limits Ankara’s room for manoeuvre in its policy towards Syria.

Turkey periodically announces military interventions in order to improve its position in relation to the other regional actors. So far, the high cost and serious risks associated with such activities have prevented Ankara from getting directly involved in the combat. This time too, these signals of Turkey’s intention to create a buffer zone are probably not a sign of any real plans, but they do serve as a warning to the PYD and IS to refrain from further expansion in northern Syria, and that they should not ignore Turkish interests. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of limited military action, resembling operations already undertaken (such as sporadic and limited artillery shelling of Assad’s forces, IS, or possibly the Kurds).

Signalling a readiness to intervene has also demonstrated to the Turkish domestic audience that the AKP retains control over policy and national security, despite its weaker showing in the last parliamentary elections.

Map

Map. Control of regions in northern Syria (as of 30 June)

Based on: http://iswsyria.blogspot.com