The Russian operation in Syria: an offer or a blackmail?

Cooperation: Krzysztof Strachota, Andrzej Wilk

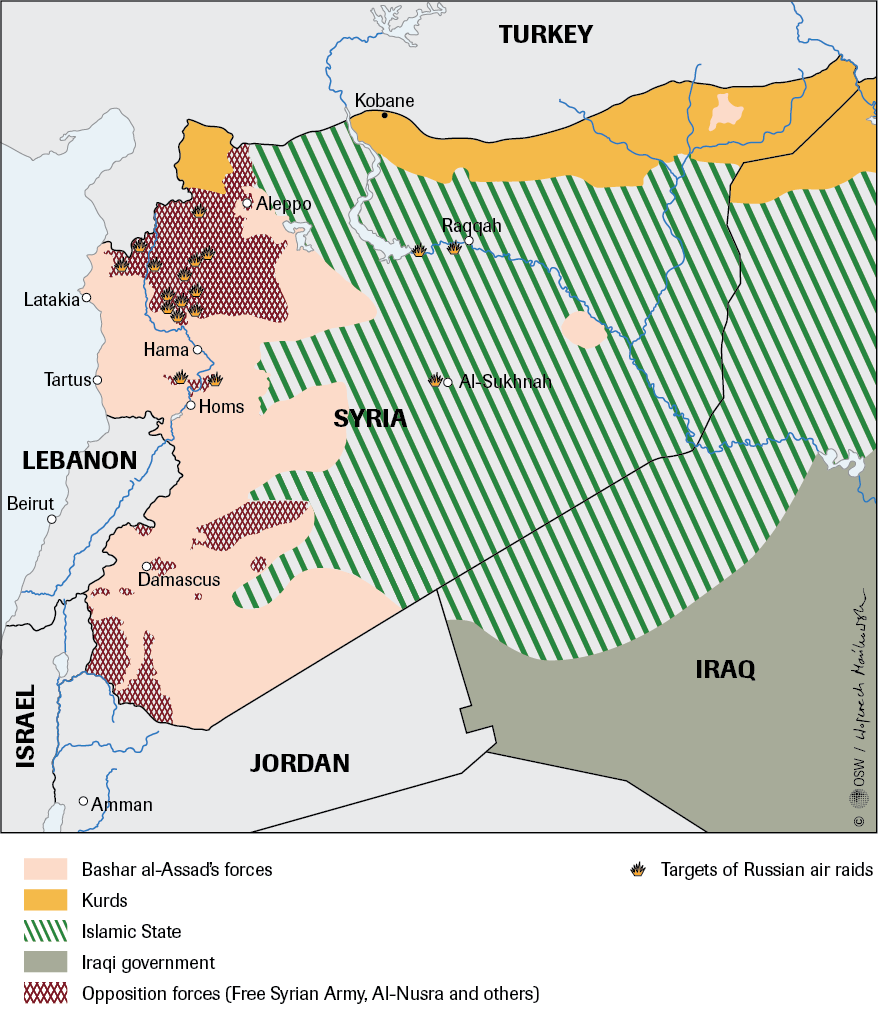

From 30 September to 5 October, a Russian air force group based at Heymim airport, near the port city of Latakia in Syria, has made over a hundred sorties, almost exclusively attacking groups supported by the United States or the Arab states and Turkey, at least twice violating Turkish airspace. The choice of targets clearly indicates that Moscow’s primary objectives are to strengthen the position of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and to demonstrate the powerlessness of the armed anti-Assad opposition’s foreign sponsors – primarily the US, but also Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The Russian air strikes seem to be a preparation for a ground offensive by the Syrian army, the aim of which would be to extend and consolidate the territory controlled by the government forces in the north-western part of the country. The Russian air operation is part of an ad hoc coalition of Russia, the Syrian government and Iran (competing with the coalition led by the US), which has been created under the banner of the fight against terrorism in Syria, and the declared objective of which is to stabilise that country and the region. On 1 October Moscow ruled out joining the US-led coalition against the Islamic State (IS) in its current form.

The operation in Syria is the first open military intervention by the Russian Federation outside the area of the former Soviet Union, and is being presented in Russia as a sign of its rise from the position of a regional power to that of a global power, a move which temporarily strengthens the internal legitimacy of Putin’s regime.

OSW analysis about the consequences of Russian operation in Syria for the region

The targets of the Russian attacks

In the period from 30 September to 5 October, Russian aircraft performed more than a hundred combat missions, almost exclusively in the north-western provinces of Syria. The targets of the raids were the Free Syrian Army, Jabhat an-Nusra and related organisations. Some of the targets are located on territory considered to be controlled by Assad’s forces. Only three of the Russian raids struck at targets located in the part of Syria dominated by Islamic State. No attacks on groupings of Islamic radicals originating from Russia and other post-Soviet states have been recorded, even though Russian propaganda has heavily emphasised that their liquidation is one of the main tasks of the Russian intervention (see Appendix). In addition, on 3 and 4 October Russian planes violated Turkish airspace, which provoked protests from Ankara and a warning from the Secretary-General of NATO. Apart from the activity by Russian forces based in Syria, on the morning of 7 October the action was joined by a team of missile ships from the Caspian Fleet, operating in the basin of the Caspian Sea. A total of one frigate and three corvettes fired 26 3M-14 Kalibr cruise missiles (with a range of 1500 km) at 11 targets in Syria.

This intervention was preceded by a significant strengthening of Russia’s military presence in Syria, mainly in the form of the air squadrons that appeared there in mid-September. The immediate pretext for this intervention was a request for help from the government in Damascus. Both countries have had close political and military relations since 1956. In the civil war which has been ongoing in Syria since 2011, Russia has always been the main source (along with Iran) of political, military and financial support for the regime of President Assad.

The international community’s reaction

The Russian campaign has been severely criticised by the United States, France, Britain, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar, and the United Kingdom. In a joint statement on 2 October, they expressed concern about the Russian air raids, which have incurred civilian casualties, and called for their cessation. Russia’s actions have been described as a mistake which will contribute to a further escalation of the conflict, and an incitement to extremism. However, this criticism of Russian policy has not been accompanied by any readiness to take real steps that could counterbalance Russia’s actions. At the same time, Western countries have signalled the possibility of entering into joint action with Russia against Islamic State and finding a compromise solution on the issue of Assad’s future. Two other important regional players, Israel and Egypt, have adopted a more restrained stance to Russia’s actions.

The official narrative and Russia’s real aims

The Russian authorities (including President Vladimir Putin) has consistently rejected accusations that it is avoiding combat with Islamic State, dismissing them as a part of the West’s information war against Russia. At the same time, Moscow suggests that in fact all the armed groups fighting the Syrian government forces should be regarded as terrorists, and insists on the need for the West to acknowledge Assad’s regime as a fully-fledged political partner in the fight against terrorism. The Russian narrative stresses that Assad is the only force capable of stabilising the situation in Syria, and that only the Russian forces have a legal basis to act in Syria due to an invitation from its legitimate authorities.

Russia’s main purpose is to use its involvement in Syria to overcome the limited international isolation in which Moscow found itself after its annexation of Crimea and its intervention in eastern Ukraine. Russia’s simultaneous de-escalation of the situation in Donbas is worthy of note here. It appears that Moscow wants to achieve two goals simultaneously by means of this two-pronged action. The first is to get the Western economic sanctions removed by January 2016 in due to its newly ‘constructive’ approach towards Kyiv. The second is to justify Moscow’s claim to superpower status by openly challenging the West in Syria. In this way, Russia, after having seen its superpower ambitions stymied in Ukraine, has tried to assert them elsewhere, where there is no risk of incurring any new sanctions.

Russia’s action also seems to be dictated by President Barack Obama’s rejection of a presumed offer by Moscow, most likely presented during talks on 28 September at the UN headquarters. This offer could have concerned a very limited Russian engagement in Syria against Islamic State, presented by Russia as being essential for the US, in exchange for Western concessions on other issues. In view of Obama’s probable disinterest, the Kremlin decided to make a ‘negative offer’, in what effectively amounted to a form of blackmail (a demonstration that Russia could harm the Americans by making it genuinely difficult for them to coordinate activities with their Syrian allies). In addition, Russia has demonstrated that it is capable of providing substantial and effective military aid to Assad.

However, Moscow has so far refrained from giving either a precise definition of the exact objectives of its Syrian operation (except for quite general declarations about the ‘war against terrorism’), or an unambiguous deadline for its conclusion. Although the head of the Duma Committee for International Affairs, Aleksei Pushkov, said on 2 October that Russia’s military operation in Syria would take three to four months, he then backtracked, stressing that the time of operation would be “limited”, and that a final decision on the matter would be taken by the military command “depending on the situation”. This indicates that Russia retains broad leeway for further action, and that its priority is to avoid tarnishing its image and getting militarily bogged down in Syria.

Moscow’s actions are mainly intended for international consumption, but they also have a domestic dimension. Although Russian society is very sceptical of the idea of direct military involvement in Syria (according to the Levada Centre, only 14% of those polled in late September supported the deployment of Russian troops to the area), the Kremlin’s decision is likely to have positive consequences for the legitimacy of Putin’s regime. Since the start of the air strikes, the conflict in Syria has dominated the official media, where Russian involvement is being presented as a strategy of “forward defence” against Islamic radicalism. The media’s consistent terrorising of audiences with the imminent threat of Islamic terrorism may, in a relatively short time, lead to a significant increase in support for the military operation, despite the persistence of the Afghanistan trauma in the collective consciousness of the Russian society. Moreover, it cannot be excluded that in the near future Russian authorities could resort to provocations aimed at making such a threat more credible. The Syrian intervention is also being portrayed as a demonstration of Russia’s rise from the status of a regional to that of a world power, which can challenge the United States and have a real influence on events on a global scale. At the same time, the Syrian theme allows the media to mask the furtive withdrawal from the ‘Novorossiya’ project in eastern Ukraine, which has not brought the Kremlin the strategic and political benefits it had expected.

Evaluation of Russia’s political effectiveness

So far, the intensity of the Russian military contingent’s activities in Syria (both the air strikes and their naval support) puts them in the same class as the medium-sized exercises regularly carried out on Russian Federation territory. In the perspective of the next few months (i.e. until the end of this year), the Syrian operation does not constitute a particular challenge for Russia from the technical, logistical or financial points of view. This could only change if their opponents employed a means of air defence capable of destroying Russian aircraft at high altitudes, or if the Russian Navy’s access to the Mediterranean Sea was cut off (first of all, by closing Turkey’s Black Sea Straits). At the moment, neither of these scenarios seems likely.

Although Russia’s actions have demonstrated its ability and determination to take military action in the Middle East, it is very unlikely that the Kremlin could rebuild a position in the region comparable to that which the Soviet Union once occupied – nor does it intend to. We can expect, however, that it will be able to save the Assad regime and (together with Iran) to enable it to carve out and consolidate a new political entity in the western and north-western parts of Syria. This will enhance Russia’s position as one of the essential players in the Middle East’s political arena.

The Russian military intervention in Syria will temporarily lead to a further cooling in its relations not only with Western powers, but also with the Arab states and Turkey. It will further deepen the distrust with which Moscow is viewed by Western capitals due to its annexation of Crimea and the military intervention in Ukraine. This will temporarily weaken Russia’s international position, and will probably make it harder to achieve its strategic objective, namely winning acknowledgement of Moscow’s importance for the stabilisation of international relations (i.e. a ‘reset’, but on Russia’s terms).

Map

Russian air raids in Syria (September 30 - October 6)

Appendix 1

The contingent of the Russian Aerospace Forces in Syria

The organisation of the base

The decision to deploy a contingent of the Russian Aerospace Forces in Syria was taken no later than early summer this year. Intensive modernisation of the Heymim base south of Latakia belonging to the Syrian Air Force was completed by mid-September. This included re-laying the runways’ surfaces and extending one of them (the eastern runway), thereby allowing heavy transport aircraft to use the airport. In addition to upgrading the existing infrastructure, the construction work included two new aprons for helicopters, a control tower, and the erection of modular homes as barracks (the residential infrastructure can house between 1500 and 2000 personnel). At the same time, equipment to modernise the base was imported from Russia via the Russian Navy’s material-technical support point in the Syrian port of Tartus (mainly by assault ships, whose increased traffic – three journeys a week – was noted by Turkey as of mid-August). Aside from the work at the Latakia airport, Russian construction brigades also modernised an airport near Tartus, from where equipment was transported to the base at Heymim, as well as the weapons storehouse in Istamo, located to the north of Latakia, and the reconnaissance station at as-Sanobar. Since the second week of September, equipment for the new base has also been supplied directly by air (including via the An-124, the heaviest transport aircraft, flying twice daily), via a route along Azerbaijan, the Caspian Sea, Iran and Iraq. The first helicopters (two Mi-24 attack helicopters and 2 Mi-8 combat support helicopters) were delivered – most likely on board transport aircraft – on 17 September. A day later, the first Russian combat aircraft (4 multirole Su-30SM planes) landed at the airport in Latakia. Most of the vehicles (the remaining helicopters and bombers and attack aircrafts) reached the Heymim base by 22 September. The last to arrive were the Su-34 bombers (29 September).

The equipment’s composition and numbers

The contingent of the Russian Aerospace Forces in Syria is equivalent to a reinforced regiment of the tactical air force (according to the Russian nomenclature) of a mixed nature, aimed at acting independently against ground targets (the bombers, assault and combat support) and in direct interaction with units operating on land (the assault planes and helicopters). The contingent’s composition includes:

- 12 Su-24M2 bombers (upgraded as part of the State Armament Programme for 2006-2015);

- 12 Su-25SM attack aircraft (as above, the contingent includes two variants of aircraft: the Su-25SM2 and Su-25SM3);

- 4 Su-30SM multirole combat aircraft (new aircraft, delivered after 2010; these serve as air cover for the base);

- 6 Su-34 bombers (new aircraft, delivered after 2008; the most technologically advanced aircraft);

- 1 Il-20 electronic signals intelligence (ELINT) aircraft (modernised aircraft, acts as an air command post);

- 10 Mi-24 / Mi-35 attack helicopters (modernised and new planes);

- 10 Mi-8 combat support helicopters (new planes).

In total, the contingent includes 34 warplanes and 10 helicopters, as well as 11 support aircraft.

The armaments for the airplanes and helicopters operating in Syria include a full spectrum of conventional weapons, including bombs and guided missiles (all the warplanes included on the list are designed to carry precision weapons). From the film footage and photos available, we can confirm that the aircraft stationed in Syria have the following types of precision weapons (laser-guided or using the GLONASS satellite navigation system):

- smart bombs: KAB-250, KAB-500, BETAB-500;

- guided missiles: Kh-25L, Kh-29L.

The most commonly used unguided weapons are the FAB-500 and OFAB-250 unguided aerial bombs.

The contingent is protected by the grouping of the Black Sea Fleet ships operating in the eastern part of the Mediterranean (the missile cruiser Moskva, the destroyer Smietlivy, the frigates Ladny and Pytlivy) and a reinforced battalion of the 810th Brigade of Marines from Sevastopol (equipped with 7 tanks, 35 armoured personnel carriers, and 15 artillery units, including 6 self-propelled howitzers and anti-aircraft rocket launchers). In late September, the base’s defences were supplemented by air by a sub-unit of the Airborne Forces, a battalion of the 7th Airborne Brigade from Novorossiysk. The sub-unit of the 336th Infantry Brigade Maritime from Baltiysk which has been mentioned in media reports is most likely intended to defend the naval base in Tartus.

The contingent’s radio-electronic defence is provided by the Vasily Tatishchev radio-electronic reconnaissance ship of Project 864, operating off the coast of Syria.

Fuel reserves for the contingent in the event of local supply problems will be provided by large Russian Navy tankers of Project 1599-B: the Ivan Bubnov (Black Sea Fleet), the Sergey Osipov and Gienrikh Gasanov (Northern Fleet) and the Lena (the Baltic Fleet). The contingent’s main supply base is Novorossiysk, and materials and ammunition will be supplied by the Black Sea Fleet’s assault ships, one arriving on average every two days (from the beginning of October, in order of their departure from Novorossiysk, these will be the Saratov, the Tsezar Kunikov and the Azov).

Andrzej Wilk

Appendix 2

The contingent’s activity in the period from 30 September to 6 October 2015

The contingent’s first flights took place on 25 September, and combat missions were launched on 30 September. So far only aircraft have been used in military actions (the helicopters remain in reserve, probably to be used as direct support to offensive action by the Syrian army). In the period from 30 September to 6 October, the bombers and attack aircraft performed over 120 flights, attacking more than 60 targets. Around a third of the missions took place at night. From sources independent of Russia, we can confirm that precision weapons were used on several occasions (see Table). In addition, several covering flights were made by Su-30SM multirole combat aircraft (on 3 October one of these planes, probably deliberately, violated Turkish airspace, provoking a reaction from Turkish air defence).

Table

The activity of the Russian contingent in Syria

|

Date

|

Number of planes |

Number of targets attacked |

Notes |

|

30 September |

20 |

6 |

|

|

1 October |

18 |

12 |

|

|

2 October |

24 |

13 |

Su-34s used guided bomb units (GBU) near the town of al-Latamna, most likely KAB-500s |

|

3 October |

20 |

9 |

Su-34s used BETAB-500 GBU near the town of Raqqa; Su-24M2s used KAB-500 GBU near Maaret-en-Nuuma |

|

4 October |

20 |

10 |

Su-34s used Kh-29L guided missiles near Jisr-ash-Shughur, and KAB-500 GBU near et-Tabka |

|

5 October |

15 |

10 |

|

|

6 October |

20 |

12 |

|

Andrzej Wilk

Read about the consequences of the Russian operation in Syria for the Middle East