The local government elections in Ukraine

On 25 October, elections to local authorities at all levels were held in Ukraine. The voting itself may be assessed positively, although the subsequent procedures have been progressing sluggishly, and some parties have accused the authorities of falsifying the results. According to still incomplete results, the Petro Poroshenko Bloc won in the majority of oblasts and regional capitals; it will be able to create majority coalitions, and even govern alone in some places. The results for the Opposition Bloc have not significantly improved the party’s presence on the political scene. There have been unexpected successes for the two parties now controlled by Ihor Kolomoyskiy, currently the most powerful oligarch in the country. Good results were also recorded by the Batkivshchyna (Fatherland) and Samopomich (Self-Reliance) parties.

The election results have significantly changed the political map of Ukraine. Kolomoyskiy has become one of the most important political players and – with the support of some other parties – may push for early elections. Batkivshchyna’s radical, populist program has helped it return to the first rank of Ukrainian politics. Svoboda (Freedom) has regained strength, while the Opposition Bloc has failed to become the sole focus for the pro-Russian and oligarchic electorate.

Problematic elections

As of 3 November, the complete election results were not known at any level of administrative division in the country. A complicated voting system had been adopted a few months earlier, including numerous innovations which were introduced without adequate preparation for the members of the electoral commissions (see Appendix); this led to many errors in determining the outcome of the elections, a need to correct the protocols, and sometimes to recounts of the votes. This sparked allegations that the election results had been falsified, expressed openly both by representatives of the Opposition Bloc, and by Samopomich and Batkivshchyna, which are members of the coalition. It is quite possible that some of these allegations are justified.

The credibility of the election results could be undermined by the fact that the Central Electoral Commission does not have a valid quorum: only four of its fifteen-member composition have served less than their statutory seven-year terms. Seven members (including the Chairman) are still serving although their term of office expired some years ago, and four seats are still vacant. The Chairman of the CEC, Mykhailo Okhendovskiy, was elected to the post in 2013, two years after the formal end of his term. President Poroshenko has prevented the revision of the CEC but has not presented any suitable candidates to parliament, despite repeated requests by some of the coalition parties.

Elections were also held in those areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts controlled by Kyiv (no attempt to organise them was made in areas controlled by the separatists). However in Mariupol, the temporary capital of the Donetsk oblast, and three other cities the local electoral commissions halted the elections on dubious pretexts (in Mariupol, there were allegations that unregistered ballots has been printed in excessive numbers). All indications are that this step was taken to prevent a good result for the Opposition Bloc in these localities; it remains open as to whether this decision was taken at a local level or in Kyiv. It remains unclear as to when the elections will be held in these places.

Unofficial election results

The official results of the elections to regional councils (oblasts), regional capital cities and the mayors of these cities are not fully known. The following data is based on information about the results of parallel vote counts conducted by the party centres and NGOs. These reports do not vary significantly, and those concerning city councils and mayors do not differ greatly from the exit poll results (although such studies were not carried out for the elections to regional councils). There is no such data for the parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts controlled by Kyiv.

According to official information, the turnout was 46.62% (compared with 52.4% in last year’s parliamentary elections and 52% in the local elections in 2010). So far, there is no data on the number of spoilt ballots, but this could probably reach as high as 5-10%.

Preliminary elections results, according to the Slovo i Dilo institute, based on unofficial data on the results of elections to regional councils; and compared to the official results of the 2014 parliamentary elections, and an opinion poll for the parliamentary elections conducted by the Rating Agency in September 2015.

|

Party |

Support in elections |

Support in 2014 |

Poll result |

|

Petro Poroshenko Bloc/Solidarity |

19.3% |

21.8% |

13% |

|

Opposition Bloc |

13.6% |

9.3% |

11% |

|

Batkyvshchina |

13.2% |

5.7% |

11% |

|

Vidrodzhennya (Revival) |

12.5% |

0.2% |

1% |

|

Svoboda |

9.8% |

4.7% |

5% |

|

UKROP |

8.9% |

– |

1% |

|

Oleh Lyashko’s Radical Party |

8.5% |

7.4% |

7% |

|

Samopomich |

7.2% |

10.9% |

11% |

These figures are only indicative. The UKROP party was founded in 2015.

The Petro Poroshenko Bloc won the elections, taking first place in 14 and second in 6 of the 23 oblasts for which data are available; it won from 11% to 29% of the vote in individual districts. The Bloc also won the council elections in 13 regional cities (including Kyiv and Odessa).

Batkivshchyna, Yulia Tymoshenko’s party, did not win the elections in any of the oblasts, despite seeing a significant increase in popularity in recent months; however it came second in eleven oblasts and won elections to the city council in Sumy. Samopomich clearly won the elections in Lviv city (32%) and came second in the Lviv oblast; it won places on the councils of 14 oblasts and 21 regional cities, thus confirming that it has become a national party. The Radical Party, which recently left the ruling coalition, will be represented on the councils of 14 oblasts and 6 cities. Svoboda, which has no parliamentary seats, won seats on the councils of 12 oblasts and 15 cities, including Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil, although it lost definitively in Lviv, giving way to Samopomich and the Poroshenko Bloc.

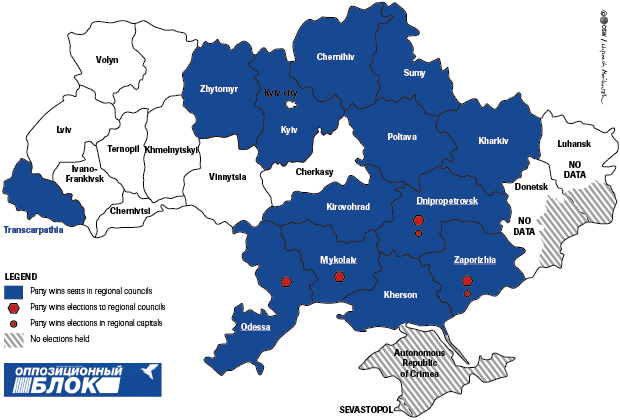

The Opposition Bloc, the main force identified with the ‘old order’, won the elections in four districts (Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhia, Mykolaiv and Odessa, winning around 20-32% support), and took second place in Kherson. The Bloc also won elections to city councils in Zaporizhia and Dnipropetrovsk, and will take seats in six more.

There was surprising success for two parties linked to the oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskiy: the right-wing patriotic UKROP and the centrist-oligarchic Vidrodzhennya (Revival). The former won elections in the Volyn region and in Lutsk, and came second in the Dnipropetrovsk oblast (as well as Dnipropetrovsk city); it will also join 11 more regional councils and 7 city councils. The latter party won elections in the Kharkiv oblast (32%) and Kharkiv city (53%), and will enter five more regional councils and one city council (Uzhhorod).

The mayoral elections in regional cities saw first-round victories only in Kharkiv, Odessa and Ternopil; the incumbents won in each case. The second round of mayoral elections will be held on 15 November; the incumbents here also have good chances of victory.

Winners and losers

These election results mean success for the Petro Poroshenko Bloc, which more or less maintained its level of support from last year’s parliamentary elections. However, this is a serious defeat for the ruling camp as a whole, because the Bloc’s main ally, the Popular Front (the party of Prime Minister Yatsenyuk), did not take part in the elections; its support has fallen from 22% in the 2010 parliamentary elections to 1% in a poll from August this year, and its previous electorate did not switch its support to the Poroshenko Bloc.

In many regional city councils the Poroshenko Bloc will be able to govern alone (as a large number of votes were cast for parties that did not cross the electoral threshold, the Bloc’s advantage is expected to rise significantly), and in the others it will be able to initiate the creation of a majority coalition. Even in those districts where the Opposition Bloc won (apart from Dnipropetrovsk), coalitions without its participation are possible.

Batkivshchyna clearly increased its electorate, which is further confirmation that the party is on the way back to join the major players in Ukrainian politics. Samopomich suffered some losses, but enjoyed major success by pushing Svoboda out of power in Lviv. Nevertheless, support for Svoboda turned out to be higher than expected; the party has strengthened its position in the centre of the country, and obtained good results in new regions (including Zaporizhia and Kharkiv). The support for the Radical Party, which was slightly higher than its results in the parliamentary elections and recent polls, suggests that this party’s electorate is stable, but expanding it any further seems unlikely.

The Opposition Bloc won strong positions in the Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhia, Mykolaiv and Odessa oblasts (and, as might be guessed, in the Kyiv-controlled areas of Donbas), but lost badly in Kharkiv; and on a national scale, its support was only slightly higher than seen in the poll results. This party has not managed to become the sole focus for oligarchic and pro-Russian forces, and particularly it failed to win the electorate of the Communists, who were forbidden to participate in these elections. Some of the Party of Regions’ members joined Vidrodzhennya or the newly-formed Our Country party, which was created by local elites who have decided to support Poroshenko (this latter group entered seven regional councils); others co-founded local parties which sometimes won seats on regional and / or city councils (such as the mayor of Odessa’s party Doviray spravam [Trust in deeds]). The Party of Regions’ electorate has become similarly scattered. On the other hand, much of the Communists’ electorate lived in Crimea and Donbas, and was thus unable to participate in the elections (which is why the Communists did not enter parliament after last year’s elections); however, neither the Opposition Bloc nor any other national party could make an attractive offer to this electorate in these elections.

The elections’ political consequences

The elimination of the People’s Front from the political scene without any substantial increase in support for the Poroshenko Bloc is an alarm call for the ruling camp. But its main opponents (both within the coalition and outside it) can also expect that in any early elections – such as Kyiv has been considering for several months at least – they will see a certain rise in their support, but not any decisive breakthrough. Early elections are in the interest of Batkivshchyna and Kolomoyskiy, who is behind two parties with different electorates, and also has considerable influence within the Radical Party, and probably also in Svoboda. In this new situation, he has become one of the key political players in Ukraine, and the arrest on 1 November of one of his closest associates, Hennadiy Korban, speaks for the fact that concern in the President’s circle at the rise of his influence is increasing.

If Poroshenko is able to form coalitions with his current allies in most of the regional and city councils (which should also strengthen his coalition in parliament), and succeed in pushing through a constitutional amendment concerning the decentralisation of the country in December, we need not expect further elections in spring. However, if these moves fail, the President of Ukraine may have no other choice than to call early elections.

Maps

Petro Poroshenko Bloc

Opposition Bloc

Baktivshchyna (Fatherland)

UKROP / Vidrodzhennya (Revival)

Appendix

The regulations for local elections in Ukraine

Local elections are held in order to determine the composition of 10,500 councils at all levels (village , settlement, city, raion (county), city district and oblast (region; made up of a total of 158,000 councillors), and separately, the chairmen of village, settlement and city councils (a total of 10,000). In these elections, candidates may stand as members of parties or as individual (non-party) candidates.

Council elections at the lowest level (village, settlement, new type communities established in the process of consolidating village councils), and for their chairmen, are held on the basis of a majority vote in single-member constituencies and are decided by a plurality. The same rules apply for the elections for chairmen of cities (mayors) with fewer than 90,000 residents.

The elections of municipal, raion, city district and regional councils are held on the basis of a proportional vote for parties’ electoral lists (the participation of groups which are not registered as parties was not permitted). Mandates are awarded to parties which win more than 5% of the votes in any given administrative unit.

Elections in cities with more than 90,000 residents (the population of the smallest regional city, Uzhhorod) hold a majority vote, (with a second round if needed). Here, too, non-party candidates may stand. This solution was first introduced in 2015.

In proportional elections, parties may (but do not have to) designate their recommended candidate in a given constituency. In this case his name is printed on the ballot; in the absence of any such designation, the name of the first candidate from the party’s list is printed. This procedure was first introduced in 2015.

The ballots, which can often be up to 150 cm/4’11” in length (in some oblasts as many as 25-30 party candidates were standing, and some majority elections had dozens of candidates), are placed into six separate ballot boxes for each separate vote.