The parliamentary election in Russia: a demonstration of the Kremlin’s power

An election to the State Duma (the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia) combined with annual local elections in the regions (for example, elections of seven heads of federal subjects and 39 regional legislative assemblies) was held on 18 September 2016 in Russia. The vote ended in victory for the “party of power”, United Russia. The party has gained a constitutional majority as a result of an election to the State Duma which was characterised by the lowest voter turnout in history. Traditionally, there was no real competition during the election and this was furthermore most probably subject to massive scale electoral fraud. However, the government employed a number of PR measures to make the election seem transparent.

The Kremlin intends to use the unprecedented dominance of the “party of power” in the State Duma to demonstrate the consolidation of the governing camp and to lay bare the weakness of the opposition (including the sanctioned opposition). It also sends a clear message to the Russian public that there is no alternative to the present government system and that the Kremlin fully controls the political processes even during an economic recession. This will also offer it more opportunities to make any changes in Russian law and the institutional system in the period preceding the presidential election scheduled for 2018.

The systemic role of the parliament and elections in the Russian Federation

The formal tripartite division of powers in Russia serves only to mask the absolute and consistently strengthened dominance of Vladimir Putin and his inner circle in decision-making processes in the country. The parliament, a façade institution, is used as one of the key tools for maintaining stability in the political system and as one of the platforms for lobbying for the interests of particular groups inside the government elite. This is why the logic of the Kremlin places great emphasis on maintaining control of both the procedure of determining the makeup of the parliament and how the deputies work.

However, this does not mean that parliamentary elections in Russia are meaningless. They play several major functions, encompassing both purely image-building ones and practical ones. The fact that elections are held is intended to legitimise the government in the eyes of the public by creating the appearance that citizens have an influence on the functioning of the state and by offering a substitute of dialogue between the government and the public during the election campaign. The promises made by the governing party’s candidates before the election, in turn, are intended to create the appearance that the public and the government elite have common interests and that the state cares for its citizens. Elections also offer the opportunity to mobilise the state administration apparatus, verify its effectiveness and to select the ‘staff reserve’ for top positions in the central and regional apparatus. The purpose which elections serve probably to the least extent is in legitimising the Russian political system on the international arena, although the determination with which the government seeks a positive opinion from some foreign observers (representatives of the CIS or Western pro-Kremlin circles) means that this factor cannot be dismissed.

Characteristic features of the parliamentary election in 2016

The 2016 election to the State Duma was held in a special context. The economic crisis has been ongoing for almost two years and it will be most probably followed by at least few years’ stagnation. The government fears public dissatisfaction with their social and living conditions, there is a geopolitical confrontation with the West, and – last but not least –it will be necessary to skilfully hold the presidential election in 2018, which will be essential from the point of view of the system’s stability. All these factors decided on the shape of the strategy concerning the election which the Kremlin adopted. Another factor which affected this strategy was the government’s memory of the protests in 2011–2012 which were accompanied by the strongest degree of mobilisation of anti-Putin circles in years.

The government was thus interested in maintaining full control of the election process, while keeping the temperature of the campaign as low as possible. Preparations for the election this year moved in three directions. On the one hand, the government tried to keep up the appearance of pluralism, political competition and the transparency of the election. The measures taken to this effect included allowing twice as many political parties taking part in the election than in 2011, a reduction in the scale of ostentatious (easy to prove) forgeries and other abuses and, last but not least, the dismissal of the head of the Central Election Commission, who was discredited in the eyes of a section of the public, and the nomination of the former human rights envoy, Ella Pamfilova, to this position in March 2016. Ms Pamfilova is moderately liberal and has a good reputation among the greater part of the independent circles (according to polls, voter confidence in the Central Election Commission significantly rose ahead of the election as a result of Pamfilova’s statements and actions).

On the other hand, the practices of restricting real electoral competition used in the preceding years continued, for example, by impeding the registration of candidates put forward by the political parties remaining outside the parliament, media bias towards the “party of power” (United Russia), supporting its candidates through the so-called ‘administrative resource’ (the instruments of formal and informal influence on the course of the election witch the state apparatus has), intimidating the opposition’s candidates, restricting independent election monitoring (the observers encountered formal and real difficulties in their attempts to access the work of the election commissions). The actions taken by law enforcement agencies, politicised courts, regional and local election commissions and local governments, which were all working hard to ensure a sweeping victory for United Russia, strongly counterbalanced the ‘liberalising’ moves made by the new head of the Central Election Commission.

Another important goal for the government was to neutralise the potential for protests by dampening public interest in the election (the low voter turnout was especially important in big cities, where opposition sentiments are traditionally stronger than in the provinces). The moves that served this purpose included the unconstitutional shifting of the election from December to September and holding the election campaign during the summer holiday season. Contributing factors were: increasing public alienation from the government during the economic crisis, and the falling interest in politics among citizens due to their being focused on their difficult financial and living situation, choosing individual survival strategies rather than group mobilisation, their disbelief that they can have any influence on the government and, last but not least, fear of repressions.

The evaluation of the course and outcome of the election

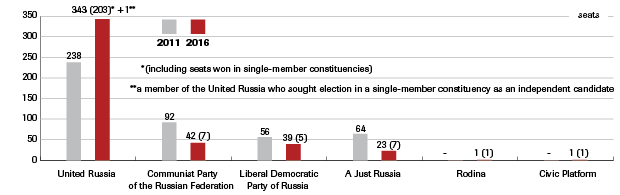

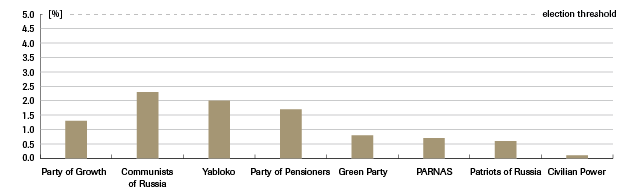

The election was a clear success for the government. Its components were: low voter turnout, the peaceful election process, and the surprisingly high result achieved by United Russia. The voter turnout officially reached 47.8% (25–28% in Moscow and Saint Petersburg) and was the lowest in the Russian Federation’s history (it usually exceeds 50%–60%). Even in occupied Crimea it was lower than the propaganda needs would suggest (49.1%, and thus only slightly higher than on the scale of the country as a whole). The official results after 99.9% of votes counted for party lists (the final results are expected to be announced on 23 September) are: 54.2% for United Russia, 13.3% for the Communist Party (CPRF), 13.1% for the nationalist Liberal-Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and 6.2% for A Just Russia. United Russia also achieved a sweeping victory in the regional election (the victory of its candidates in the first round of the gubernatorial elections in all the seven regions was accompanied by the party winning the highest number of seats in the elections to the 39 regional parliaments). Protest sentiments did not intensify during the election. Nor should demonstrations be expected after the election, especially given the fact that none of the opposition parties have criticised it especially strongly.

There is a large body of indirect evidence of large-scale electoral fraud during the parliamentary election. The result achieved by United Russia is clearly higher not only than the forecasts ahead of the election but even (by around 10 percentage points) the results of the exit polls conducted by the governmental research centre WCIOM (by comparison, WCIOM’s exit poll results in 2011 differed from the official results by less than 1 percentage point). The fact that as many as 35–40% of the respondents refused to reveal who they voted for in the exit polls may mean that at least part of them cast their votes for political parties other than United Russia. It is worth paying special attention to the scale of difference as regards the results achieved by Yabloko (as much as 3.5% support in exit polls against 2% according to official data). Furthermore, the official results mean that the party has been deprived of the right to be financed from the state budget which it had acquired in connection with its result in the election in 2011 (3.4%). The fraud may have reach a particularly large scale in some of the regions which, like most republics in the Northern Caucasus and Tatarstan, not only had unusually high voter turnout (from around 80% to over 90%) but also very high support for United Russia (70–90%, the highest being in Chechnya: over 96%). At the same time, the reduced number of noticeable, easy to denounce violations of the election procedure suggests that strong emphasis was placed during the September election on manipulations that are difficult to prove, in particular falsifying the reports compiled in polling stations.

What also helped United Russia was the mixed voting system, which allowed the “party of power” to achieve a sweeping victory in single-member constituencies owing to the employment of the so-called ‘administrative resource’. Another factor was the weakness and fragmentation of the political opposition resulting not only from the government’s repressions or manipulations but also from the lack of charismatic leaders and appealing manifestos, and also the opposition’s insufficient understanding of the mentality and needs of the public.

The fact that the government intentionally made citizens less interested in the vote and that the election results were most likely forged on a major scale also proves that the election shows held by the government require an audience to a decreasing extent: the centre of gravity is moving more and more from a government-public interaction to an interaction inside the government elite in the broad sense of the phrase. The election results lead to the conclusion that the government’s goal this time was not only to legitimise the election but also to achieve an ostentatious victory for the government party. The latter is important in two dimensions. In the symbolic dimension it manifests the ‘unity of the nation and the government’ at a time of crisis, and in the longer term may also mean further centralisation and personalisation of the government system (United Russia in its election campaign skilfully used the slogan of loyalty to the president whose support levels exceed 80%). In the purely pragmatic dimension this means that United Russia has gained a record-high majority in the State Duma (most likely 76%, which is clearly above the two thirds majority needed to amend the constitution). This means that a single political party may take full control of the legislative process and also an ostentatious withdrawal from the affected pluralism existing in the parliament so far – the opposition sanctioned by the system will now only play a purely decorative role.

The success in organising this election result at the same time proved that the system and the state administration staff (including the new head of the Presidential Administration, Anton Vaino, who was nominated for the post in August 2016) passed the test of effectiveness ahead of the presidential election. The fact that the State Duma has become fully dominated by United Russia also makes it possible to carry out a major institutional and staff reshuffle which requires a stable and dependable political base (this, then, serves as further proof of the Kremlin’s increasing distrust of the satellite parties at a time of crisis). Even constitutional amendments may be pushed through by a single party, if the Kremlin finds it necessary to keep control of the system in the conditions of the economic crisis (the possible amendments could concern, for example, the scope of the president’s competences or the procedure of electing the president).

APPENDIX

Preliminary official results of the parliamentary election in Russia provided by the Central Election Commission

Chart 1. Percentage of votes cast for party lists (5% election threshold)

Chart 2. Total seats won – forecast

Chart 3. Results achieved by other parties (they did not make it to the parliament)

Source: Central Election Commission