Turkey on the brink of disaster in Syria

On 7 September a summit was held in Tehran attended by Presidents Hasan Rouhani, Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The subject of the talks was the Syrian army’s ongoing offensive in Idlib province which Russia and Iran are actively supporting. Located in north-western Syria, Idlib is the last major area controlled by the Syrian armed opposition, which is operating under a political umbrella provided by Turkey. Ankara’s goal was to convince Tehran and Moscow – Damascus’s patrons – to halt the offensive. The talks ended in failure, and on 9 September Turkey moved to increase its presence in the province by sending a convoy of around 300 military vehicles. Alongside this, President Erdoğan expressed his strong criticism of military action that may lead to a humanitarian disaster, and called on the international community to react in a decisive manner.

Commentary

- The aim of the offensive by the Syrian government forces, supported by Russian air forces, Iranian forces, Lebanon’s Hezbollah and the Syrian Kurds, which was launched on 4 September, is to eliminate the last stronghold of Syria’s Sunni opposition. Around fifty thousand rebel fighters from various organisations operate there, the largest of them being the extremist coalition Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra, which is considered a terrorist organisation by the EU). At present, Idlib’s population is estimated at around 3.5 million individuals, including one million people displaced from other provinces. Since the beginning of the conflict, Idlib has been a major opposition stronghold. In recent years, it has become a place to which fighters and their families were evacuated from areas regained by the Syrian government forces. If the regime forces and their allies regain Idlib, that would spell a final victory for Bashar al-Assad. Moreover, it would trigger a repeated scenario resembling the actions of the government forces in Aleppo, where the civilian population were forcibly displaced (mainly to Idlib and further on to the EU). The fall of Idlib will trigger a humanitarian disaster and a massive inflow of refugees to Turkey (the first groups of civilians heading for the Turkish border have already been spotted).

- For Turkey, the survival of Idlib is of fundamental importance. Since the beginning of the conflict in Syria (in 2011), Ankara has acted as a patron to the Sunni opposition and an advocate of the war’s civilian casualties – this is the basis the authorities have used to build their prestige at home and in the Islamic world as a whole. Moreover, Turkey is the guarantor of the so-called de-escalation zone in Idlib, pursuant to the Astana agreements made with Russia and Iran (it maintains military posts in the zone). The expected fall of Idlib would expose Turkey to the need to take in an accumulated wave of refugees, including frustrated rebel fighters. Ankara would be unable to manage this task, particularly in the situation of Turkey’s looming economic crisis. At the same time, combined with the controversy sparked by the recently introduced presidential system, any further crisis connected with the possible failure of Turkey’s policy towards Syria may trigger serious domestic problems.

- The ongoing crisis in Idlib has revealed the major limitations of Turkey’s foreign policy. Despite major political investments, Ankara has no effective allies in Syria or the Middle East. Moreover, it cannot count on support from the United States, its biggest ally; the relations between the two states are the worst in decades. The pro-Russian shift in Turkey’s politics, which has been in place since 2016, has brought no results. Moscow is targeting Ankara’s strategic interests by demonstrating the imbalance of its relations with Turkey. To some extent, Turkey can count on understanding from the EU (this has been confirmed, for example, during the German foreign minister’s visit to Turkey on 6–7 September). Although the EU is concerned at the possible new stage of the migration crisis, it has little to offer by way of genuine support. Regardless of the course and the reach of the offensive on Idlib (and of the future of Turkish-controlled Afrin in Syria, and the areas adjacent to it), Turkey has very little possibility of defending its own interests, let alone of regaining the political initiative.

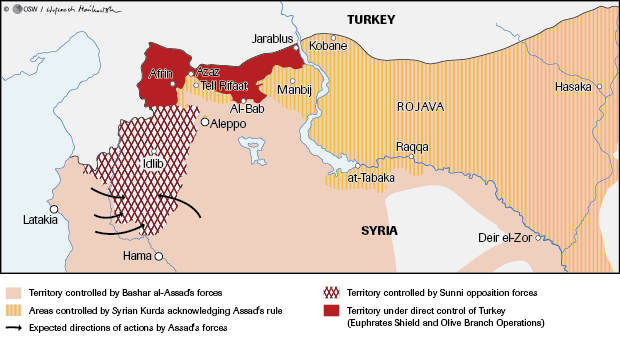

Map. The situation in north-western Syria, early September 2018