Germany: compromise on the departure from coal

On 26 January, the Commission for Growth, Structural Economic Change and Regional Development (also known as the coal commission commission) published its final report on Germany’s plan to give up the use of hard coal and brown coal as fuels. The commission had worked on the 336-page document since June 2018; the report is intended to serve the German government as a basis for the adoption of the relevant laws during 2019. According to the report, Germany will end the use of coal by 2038 at the latest, but coal power plants with a total capacity of 12.5 GW (of the 45.4 GW in use today) should be turned off by 2022. In 2032 the possibility of hastening the closure of all mines and lignite power plants by 2035 is to be examined. The federal provinces where these power plants are located are supposed to receive €40 billion from the federal budget over the next 20 years for restructuring. This money is intended to finance early retirement for workers in the lignite sector, as well as regional development in three provinces in the west (Lower Saxony, Rhineland-Palatinate and the Saarland) and east of the country (Brandenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt).

Reactions to the long-awaited decision have so far been mixed. Politicians from the ruling coalition have reacted positively to the commission’s recommendations, and opposition politicians from the Left and the Greens have reacted similarly. However, the compromise was criticised by politicians from the liberal FDP and the populist Alternative for Germany (AfD). The liberals’ criticism particularly relates to the methods for achieving the objectives of the proposed energy and climate policy. The FDP accuses the government of ‘manually steering’ business activity, and of making lavish promises of high subsidies from the state budget. For its part, AfD criticises the proposals to liquidate thriving industries and warns of the energy price rises which (according to the party) will result from quitting coal. AfD is the only party in the Bundestag which has called the fight against climate change into question.

For trade union representatives, the compromise is satisfactory. It both provides economic security to those people who choose early retirement, and guarantees funds for the development of the mining regions through investments in the transport and energy infrastructure and in tourism. Leftist circles welcomed the commission’s recommendation to suspend the plan to cut down the Hambach Forest in order to extend the open-cast mine. However, some conservation-centred NGOs have criticised the commission’s recommendations as being insufficiently ambitious. In their view, Germany can afford to turn off its coal power plants more quickly, even as early as 2030, which would greatly accelerate the reduction of CO2 emissions so the targets of the Paris climate agreement could be reached. Meanwhile, representatives from industry reacted with apprehension to a possible rise in the cost of electricity, especially as the brown coal power plants currently produce the cheapest energy of all the conventional fuel sources.

Commentary

- Although the majority of the German public supports the acceleration of the plan to close coal power plants (depending on the study, between 70% and 80% support the coal exit), the decision has been opposed by trade unions representing workers in heavy industry and mining, as well as the heavy industry lobby. In 2015, under pressure from protests by the trade unions, the government of the time abandoned the idea of imposing additional taxes on the most heavily polluting coal-fired plants. In 2016, the government’s ‘Climate Protection Plan to 2050’ strategy document included a recommendation to appoint a commission for the withdrawal from the use of coal. During the 2017 election campaign the subject was raised in the manifestoes of all parties, and was also one of the key issues in the initial coalition talks between the CDU/CSU, the FDP and the Greens in October 2017. Finally, the appointment of the coal commission was included in the coalition agreement between the CDU/CSU and the SPD which the parties entered into in March 2018. Negotiations in the coal commission proved to be difficult; the announcement of its report’s recommendations was postponed, and the talks were joined by Chancellor Angela Merkel herself, in order to ensure that a compromise was reached. The biggest controversy involved the amount of compensation for the regions affected by the closure of the mines and the lignite power stations; around 20,000 people work in this sector in Germany, but the sector indirectly provides employment to between 42,000 and 74,000 people in the country as a whole.

- The energy industry has been expecting the decision to quit coal for several years. Back in 2016 the largest German energy companies E.ON and RWE spun off companies to manage the declining power plants which run off fossil energy sources (coal and gas) from those which invest in producing energy from renewable sources and manage the electricity grids. The companies have learned from the rapid departure from atomic power which the CDU/CSU-FDP coalition announced without notice in 2011 and negatively affected the energy industry. Germany also has experience with phasing out hard coal mining, a process which began in the 1960s and ended in 2018 with the closure of the last two mines, but still generated very high subsidies – over €160 billion from the 1970s.

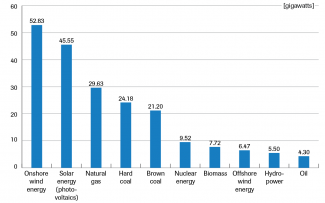

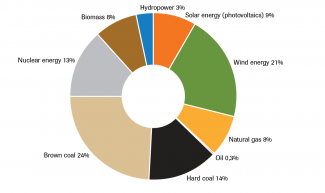

- The departure from coal should not jeopardise the security of Germany’s electricity supply. The energy from hard coal and brown coal (38% of production in 2018) is to be replaced by electricity from RESs and gas power plants. Under the current strategy, the share of renewables in German electricity production is expected to rise from 41% in 2018 to 55-60% in 2035 and 80% in 2050, but given the current pace at which renewable energy sources are being developed, this share may rise even higher. At the same time, the production of electricity from gas power plants is rising; this may meet up to 40% of demand by 2038 (8% in 2018). Moreover, the increase in the share of RESs will require the expansion of the transmission network in Germany along a north-south line in order to transfer electricity from the north of Germany and Europe to the industrial centres in the south of the country. The biggest challenge will be to balance the electricity system when the nuclear power network is switched off (in 2022), together with most of the coal plants. Germany will not be able to rely on imports of electricity from abroad during periods of increased demand while production from RESs is low (for example, if the weather is not appropriate), because the closing of coal-fired power stations is a pan-European trend (the installed capacity of coal-fired power in the EU is expected to fall by two-thirds in the period from 2016 to 2030).

- It is uncertain as to how the energy transformation will be financed. The final cost will likely be much higher than the €40 billion promised to the federal provinces, as higher energy bills for consumers should also be considered. So far, maintaining competitive prices for industry has been Germany’s priority, and it should be assumed that this will remain the case in future, even at the expense of rising energy bills for individual customers.

- The adoption of the coal commission’s recommendations has brought Germany closer to achieving the national target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 (the target for the energy sector is 62%). Due to problems with the reduction of CO2 emissions, last year Germany found itself in a group of countries which was blocking the European Union’s environmental ambitions. Berlin opposed the EU’s plan to raise the share of renewable energy consumption from 30% to 33% in 2030, and to raise the target for reducing CO2 emissions from 40% to 45% by 2030. The current compromise signals to the European Commission and the member states that in the area of electricity Germany will reduce its emissions as part of its domestic compromise, and in the future it may even work to push through anti-coal regulations at EU level, although Germany is still the biggest consumer of coal in the EU (before Poland and the Czech Republic).

- The coal commission’s recommendations have been accepted with equanimity by the Czech companies EPH and PPF, owners of the LEAG company operating lignite mines and power plants in the Lusatian coalfield in Brandenburg, which cover around 10% of demand for electricity in Germany. LEAG was created in 2016 from assets acquired from the Swedish company Vattenfall (which had suffered losses to both its business and its image) for a nominal amount. In addition, EPH and PPF took over €1.7 billion of funds from the previous owner which had been earmarked for land reclamation after the end of mining operations. The company generated a profit of €164 million in 2017. The Czech company EPH is pursuing a similar strategy in France, where it is negotiating with the German company Uniper to take over two coal-fired power plants, even though they are anticipated to close in 2022.

Additional research by Krzysztof Dębiec

Appendix