Russia’s new government: managers of a transitional period?

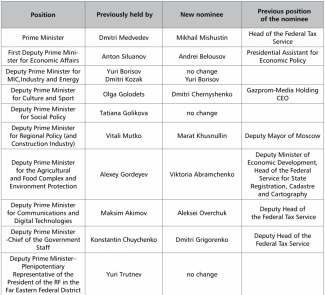

President Vladimir Putin, following his conversation with Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, signed a decree nominating the new government of the Russian Federation in the evening of 21 January. Unlike with the previous cabinet, which took almost two months to be formed (March–May 2018), this time it took less than a week. This proves that the reshuffle had been prepared in advance. The government has undergone a major change: only three deputy prime ministers (one-third of the total) have retained their positions, and almost half of the ministers have been replaced. Some structural changes have also been introduced: the Ministry of North Caucasus Affairs has been liquidated (the only ‘territorial’ ministry operating at present is the Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East), and its powers have been taken over by the Ministry of Economic Development. There has also been a shift between the competences of the Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of Finance.

Commentary

- The government has primarily been entrusted with the implementation of two Putin’s flagship initiatives aimed at boosting Russia’s socio-economic development during his fourth presidency. Firstly, it is expected to efficiently fulfil the social promises (including the ‘demographic package’) presented in Putin’s annual ‘State of the Nation’ address on 15 January. Secondly – to implement the ‘national projects’ launched in 2018. Among the latter,the government’s priority areas will be healthcare, social policy, development of digital economy, electronic budget and construction industry). It was problems with implementing these ‘national projects’ that served as the formal reason for Putin’s criticism of the previous government, led by Dmitri Medvedev. Putin has also tasked the new government with “strengthening Russia’s statehood and its position in the global system.”

- The latest major reshuffle in the Russian government is a response to citizens’ growing dissatisfaction with the condition of the state (above all, with the government’s social policy), and a follow-up to Putin’s January address, where he required to improve the quality of economic management. This reshuffle also reflects the gradual rejuvenation and ‘technocratisation’ of Russian ruling elite, a tendency which has been strengthening over the past few years.

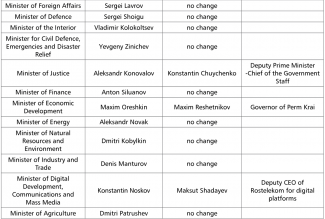

- The officials in charge of the so-called ‘presidential ministries’ (mainly tasked with law enforcement, which are directly supervised by Putin) have maintained their positions, with the exception of the minister of justice (Andrei Konovalov has been replaced by Konstantin Chuychenko, who until recently served as deputy prime minister and chief of the government staff). Contrary to rumours, minister of foreign affairs Sergei Lavrov has maintained his position (he has performed this function for almost 16 years and, according to unofficial information, has asked to be dismissed on numerous occasions). This is proof of the Kremlin’s intent to continue the previous foreign and security policy line.

- The make-up of the so-called ‘economic bloc’ has also been modified: the previous first deputy prime minister for economic affairs (Anton Siluanov) and the minister of economic development (Maxim Oreshkin) have lost their positions. Siluanov has been replaced by Andrei Belousov (so far Putin’s assistant for economic affairs), and Oreshkin by Maxim Reshetnikov (Oreshkin has been appointed as Putin’s assistant). The most conspicuous change is the lowered status of Anton Siluanov. Although he has maintained his position as the minister of finance (as such he will continue to supervise the Federal Tax Service, led until recently by the incumbent prime minister Mishustin), he will no longer be the person in charge of the government’s economic policy. It seems that this decision was made due to a change in priorities rather than Putin’s dissatisfaction with Siluanov’s work. Siluanov has successfully managed public finances and maintained budgetary discipline during a time of economic crisis and stagnation, which resulted in a significant budget surplus. However, from now on, the most important task will most likely be to stimulate economic growth and investments, and to implement the policy of social transfers. Hence, the new person in charge of the government’s economic policy is Andrei Belousov, the main author of the ‘national projects’. His role in the government will most likely be not only to control the implementation of the projects but also to monitor the work of the prime minister and his entire cabinet. This is expected to enable the president to focus on the strategic ‘succession of power’ project (finding a successor to the presidency) before 2024.

- The position of deputy prime minister Yuri Borisov has been strengthened ( Borisov is a retired military officer, and former deputy minister of defence). He has been entrusted with supervising not only the Military-Industrial Complex (Оборонно-промышленный комплекс, OPK) but also the entire industrial sphere and energy sector. Until recently, the latter were supervised by Dmitri Kozak, Putin’s trusted aide and his ‘hatchet man’, who has been appointed deputy chief of the Presidential Administration. This change may signal the intention to subordinate a major part of the real economy to the state’s defence needs.

- The ministers from the so-called ‘social bloc’ (healthcare, labour and social policy, education, science and higher education) have all been dismissed; however Tatiana Golikova, the deputy prime minister in charge of social affairs, has maintained her position. The dismissals of the unpopular ministers are proof of the desire to improve the government’s image and add credibility to Putin’s social promises (including combating poverty and improving the condition of healthcare, which has a very bad reputation in Russia).

- There has also been a reshuffle among the section of the government responsible for culture and sport. Deputy prime minister Olga Golodets, who had been in charge of this sphere, has been replaced by the CEO of the Gazprom-Media holding, Dmitry Chernyshenko. The minister of culture Vladimir Medinsky, a controversial figure due to his aggressive statements concerning politics of memory and his conflicts with some artists, has been replaced by his former subordinate Olga Lyubimova, who until recently served as the director of the cinematography department at the ministry of culture. This may signify a desire to make the state propaganda more effective, including by employing advanced mass communication technologies. The dismissal of the previous minister of sport was most likely the result of Russia’s spectacular failures due to doping scandals and sporting sanctions.

- The new nominations have potentially strengthened the position of Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin inside the government elite. According to some commentators, his political career is bound to lead him in the future to the highest positions in the federal government. As many as three of his former associates are presently members of the cabinet: Marat Khusnullin, Maxim Reshetnikov and Vladimir Yakushev.

- There is much evidence suggesting that Mishustin had a significant influence on the selection of the cabinet members (with the exception of the presidential ministries). Three out of the nine deputy prime ministers (Grigorenko, Overchuk and Abramchenko) are his former associates, and three other deputy prime ministers (Golikova, Khusnullin and Chernychenko) have had friendly relations with him. It seems that the new cabinet members have been selected in a manner that will minimise the risk of conflicts or power games that might adversely affect the cabinet’s work. This is probably one of the reasons why two strong political players, Aleksei Gordeyev and Dmitri Kozak, one of whom served as the deputy prime minister for agricultural affairs and the other as the deputy prime minister for energy in the previous cabinet, had to leave.

- However, this does not mean that the government’s political role will grow. Everything suggests that the Mishustin cabinet will be a technical government of experts expected to efficiently implement the presidential socio-economic projects and digitalisation of the state administration (as Mishustin did at the Federal Tax Service). In the Kremlin’s opinion, these two issues are vital elements in strengthening the legitimacy of Putin’s regime and providing a substitute for the real modernisation of the state in a situation of growing public discontent.

- The government reshuffle is part of the process of introducing deeper political changes in Russia announced by Putin in his address on 15 January. Their horizon is determined by the so-called ‘succession of power’; this means that someone will replace Putin as President, but Putin will maintain control of the key political processes in the country (for more details see the OSW analysis Putin’s address and the government’s resignation: the start of the succession process in Russia). It cannot be ruled out that Mishustin’s cabinet of technocrats will initially receive a credit of trust from the public, but the effect of this refreshed image may pass quickly. The government is unlikely to achieve any major successes in the socio-economic sphere, as the real reason for the economic stagnation and the deteriorating living standards of the Russian public is not the make-up of the cabinet but the logic of the Russian socio-economic model. This model serves above all the vested interests of the corrupt government elite, and is unable to generate sustainable economic growth. The poor quality of management at the various levels of the state administration is also caused by factors inherent in the system. They include an intentional ambiguity of legal regulations; the centralisation of the decision-making processes and their non-transparent nature; and – last but not least – the political and business infighting within the ruling elite, in which law enforcement structures are frequently involved.

- Therefore, Mishustin’s considerable management skills may bring only limited results. Hence, his government will most likely be a transitional one. Nevertheless, its individual members – provided that they prove their effectiveness and usefulness to the Kremlin – can earn a strong position in the gradually renewed ruling elite in the period before and after the so-called ‘succession of power’.

Additional research by Marek Menkiszak

APPENDIX

Members of the government of the Russian Federation led by Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin