Norway: centre-left takes the helm

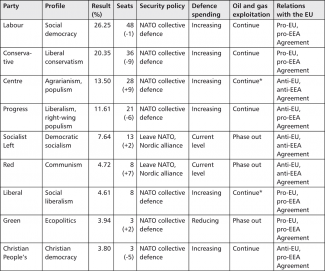

The centre-left won a majority in Norway’s parliamentary election held on 13 September. This marks the end of the centre-right governments led by the Conservative Party (Høyre) with Erna Solberg as prime minister (2013–2021). The winning social-democratic Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) is set to face difficult coalition talks with the populist and rural-focused Centre Party (Senterpartiet) and the Socialists (Sosialistisk Venstreparti).

As a result of the election, Labour Party leader Jonas Gahr Støre (born 1960) will become prime minister. He took over the leadership of the party in 2014 after Jens Stoltenberg became NATO Secretary General. Støre is a politician with extensive government and international experience, representing the section of the Labour Party closer to the centre of the political scene. After receiving his education at the Sciences Po in Paris, he was a high-level official in the Prime Minister’s Office under three prime ministers in the 1990s. Following a break to work for the WHO, Støre headed the Prime Minister's Office in Stoltenberg's first government (2000–2001) and held the posts of foreign minister (2005–2012) and health minister (2012–2013) in his second cabinet. Støre is a naval officer. His family owns a large fortune and he personally is a millionaire.

Commentary

- The Labour Party winning the highest share of the vote and the Centre Party and left-wing party’s good performance added up to victory for the centre-left block (see Appendix). The centre-right block's weaker result is due to voter fatigue with the two terms of Prime Minister Solberg, disputes between the Conservatives and the right-wing Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet), which left government in 2020, and the dilution of the "pandemic dividend" related to public support for the government's handling of the emergency during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Støre now faces a dilemma regarding the choice of coalition partners. The two most likely scenarios are a majority cabinet with the Centre Party and the Socialists, or a minority cabinet with the Centre Party. The first option would bring frequent coalition tension, and the second would mean having to seek broader support in parliament among the left-wing parties or the centre-right opposition. Norway has a strong tradition of minority governments and decision-making based on political consensus. Far-reaching changes should not be expected in the strategic areas of foreign and security policy, oil and gas extraction, or relations with the EU, where there is cross-bloc agreement between the two largest parties – the Labour Party and the Conservatives. However, the course correction may affect tax changes in the oil and gas sector, halting further extraction projects in Norway’s High North, or balancing the close military ties with the US with a greater emphasis on dialogue and cooperation with Russia.

- The future of the oil and gas industry was of key importance during the election campaign. The active campaigning of the Green Party, a new report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and protests by Norwegian environmental groups in August (including blockading the Sture oil export terminal and the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy), have all contributed to this. However, the main political stakeholders – Labour, the Conservatives, the Centre Party and the Progress Party – reject calls to phase out hydrocarbons. The largest parties are in favour of continuing exploitation (as is the majority of society) and modernising the oil and gas industry. This includes technologies to reduce emissions, the electrification of offshore platforms, and investments in renewables. The oil and gas sector is set to generate 14% of Norway’s GDP and 41% of its exports this year. In Norway, with a population of 5.3 million, this industry employs around 200,000 people, directly and indirectly. Therefore, it is unlikely that Norway’s centre-left will follow Denmark in stopping new oil and gas licensing and halting extraction by 2050. Some tax changes unfavourable to the industry and the banning of further extraction projects in the northern part of the country and in the Arctic are possible instead. Nevertheless, this may be one of the last such 'pro-oil and gas' parliaments, due to a generational change in Norway’s politics. Most party youth organisations prioritise the fight against climate change and are increasingly opposed to hydrocarbons.

- Labour will uphold Norway’s foreign and security policy baseline consisting of NATO membership, cooperation with the US, and the continued modernisation of the armed forces. These are areas contested by the Socialists. They oppose increasing defence spending, want NATO membership to be replaced by a Nordic alliance, and criticise what they see as the excessive US military involvement in Norwegian defence, which puts Oslo at odds with Moscow. However, the framework for foreign and security policy will mostly be set by the Labour Party, which has endorsed the allocation of 2% of GDP to defence and expanding the armed forces. Labour will continue Solberg's policy of tightening military cooperation with the US in response to the threat from Russia. This has involved the rotational presence of US forces in the country and the intensification of military exercises (in 2022, roughly 40,000 Norwegian and allied soldiers will participate in the Cold Response exercise in northern Norway). At the same time, in addition to deterrence, the Labour Party will approach relations with Russia placing a stronger emphasis on dialogue, cross-border cooperation, confidence building measures and contacts between both societies, which will receive support from the left-wing parties. The first test for the new government will come this autumn with the parliamentary debate on consent for the new Supplementary Defense Cooperation Agreement with the US, signed by the outgoing government in April. It provides US forces with access to military infrastructure in southern and northern Norway. It is very likely that the agreement will come into force due to the support of the Labour, the Centre Party and the centre-right parties, but it will face fierce criticism from the left-wing. This is likely to reveal tension in the new government regarding the course of defence policy.

- Another debate will relate to Norway's relations with the EU. The Agreement on the European Economic Area, in force since 1994, made it a part of the single market which means implementing the EU’s single market legislation. The Centre Party and the Socialists want to develop a more sovereign relationship with the EU, looking for possible alternatives to the EEA Agreement. Particular criticism is levelled at the free movement of people, the 4th Energy Package, the oversight of the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators, and the 4th Railway Package. Arguments have also been raised that Norway's main trading partner, the UK, has left the EU, which reduces Norway’s exports to the single market and opens up the opportunity for Oslo to negotiate a trade agreement with the EU (similar to the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement).

Appendix. Norwegian parliamentary election results and party stances in key areas

* Phase out after 2050.