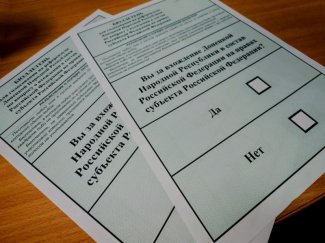

Sham Russian ‘referendums’ in Ukraine

On 23–27 September, ‘referendums’ on the annexation of four Ukrainian regions to Russia were held in the occupied territories in Ukraine. They were organised in the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (Donetsk oblast; DPR), the Luhansk People’s Republic (Luhansk oblast; LPR) and the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts of Ukraine, as well as in the Russian Federation. According to the ‘results’ reported by the Russian authorities on 28 September, the overwhelming majority of those eligible took part and voted for annexation. On the same day the leaders of the puppet para-states, the DRP’s Denis Pushilin and the LPR’s Leonid Pasichnyk, travelled to Moscow to conclude ‘agreements’ on their annexation to Russia.

The conduct of voting in Ukraine

The Russians could not ensure the smooth functioning of polling stations during the sham vote in those areas covered by the military and covert activities of the Ukrainian forces. The pseudo-referendums could be held in the larger towns (such as Kherson, Berdiansk and Melitopol), although even there the use of mobile ballot boxes was preferred. Multiple ballots were cast by the same people, and others were forced to vote on behalf of absentees. The fraudulent character of the ‘plebiscite’ is also confirmed by the fact that the organisers had no voter registers prepared, nor data on how many inhabitants remained in the temporarily occupied territories. The occupation authorities declared the ‘referendums’ to be valid as early as the second day, as allegedly more than 50% of those ‘eligible’ had participated. They also maintained that the majority of voters were in favour of joining Russia, and that the results were a foregone conclusion. Several incidents of sabotage by Ukrainians (explosions near facilities controlled by the occupiers) were reported.

Voting in Russia

The falsification of ‘referendums’ was made easier by opening over 600 polling stations in Russia and occupied Crimea, where temporarily ‘displaced’ (in fact forcibly deported) residents of the occupied territories could vote. Voting took place both inside and outside polling stations, ostensibly to facilitate the process. However, online voting was not employed, despite having been previously announced. According to the official (unverifiable) data, the following numbers allegedly voted in favour of annexation at polling stations in Russia: for Kherson oblast, 32,135 people (96.75%); Zaporizhzhia oblast, 38,762 (97.81%); Donetsk oblast, 441,485 (98.69%); and Luhansk oblast, 394,250 (97.93%).

Propaganda setting

Russian propaganda reported extensively and in great detail on the course of the pseudo-referendums, which were one of the leading topics on television. They were presented as a final ‘act of historical justice’ and the ‘return home’ for a population suffering repression by the ‘Nazi regime in Kyiv’. The coverage consistently failed to cast doubt on the results, which were described as obvious and predictable, and would naturally lead to the regions’ swift incorporation into Russia. Much attention was paid to quoting the opinions of foreign ‘observers’ (some 130 of whom from 40 countries were present; most of them were activists from pro-Russian organisations operating abroad). They fervently argued that the vote had been widely supported, spontaneous and without coercion, lending credence to the alleged fairness of the ‘referendums’. Moreover, the focus was on emotional, detailed and direct accounts of voters expressing their joy at ‘returning to the Russian homeland’.

Ukrainian reactions

The pseudo-referendums were condemned by both Ukraine and Western organisations and states, as well as by many other countries. In response to the announcement of their ‘results’, Kyiv took a firm yet calm stance, declaring them invalid and stressing that they would not have any legal consequences for the Ukrainian state. President Volodymyr Zelensky stated that the annexation precluded any peace talks with Russia. Kyiv also rejected the Kremlin’s attempt at blackmail: the Kremlin has stated that the Ukrainians’ continued fight to liberate the annexed regions would be treated as a direct attack on Russia, which could escalate the conflict. The Ukrainian government has also stated that the hasty decision to hold ‘referendums’ was an ‘asymmetrical’ response to the successful Ukrainian counter-offensive in the Kharkiv region, and a manipulation serving to mask Moscow’s own failures. The authorities in Kyiv have initiated criminal proceedings against those involved in organising the illegal ‘plebiscites’, declaring their activities to be a crime against the integrity of Ukraine.

International reactions

In a communiqué published on 23 September, the G7 leaders announced that they would not recognise the pseudo-referendums, and declared their readiness to introduce further sanctions against Russia. The US stated that it was monitoring the voting situation, and would take concrete action if Russia decided to annex the regions. A NATO communiqué also announced its intention not to recognise the results of the vote, and also offered unequivocal criticism of the possible annexation of the occupied territories. At the same time, its member states declared their willingness to continue to support Ukraine politically and practically in its war of defence. A similar stance was adopted by the institutions and individual states of the European Union. On 27 September, the vast majority of UN Security Council members (apart from Russia, China and India) expressed an unequivocally critical stance towards the so-called referendums. In doing so, they emphasised the need to respect the principles of the UN Charter, including the territorial integrity of Ukraine within internationally recognised borders. Unambiguous declarations on non-recognition of the results of the ‘plebiscite’ also came from the governments of Turkey, Serbia and Kazakhstan, among others.

In response to the pseudo-referendums and the expected further escalation of hostilities, Western states are extending sanctions on Russia, or have announced such steps. On 26 September, the UK placed further restrictions on officials (33 persons, including representatives of the self-proclaimed authorities) and legal entities (including Goznak, the monopoly producer of state documents including internal passports) involved in organising the ‘plebiscites’. Among others, Iskander Makhmudov, an oligarch with assets in the metallurgy sector, was added to the British list. Meanwhile, Japan has sanctioned selected Russian research institutes and banned the export of goods and materials which could be used to produce chemical weapons to the country.

The EU and the US have also announced an extension of restrictions against Russia. More individuals and legal entities, including those in the occupied regions of Ukraine, will be subjected to restrictions. The US Department of Justice has asked Congress for legislative changes to allow frozen Russian financial assets to be used to support Ukraine. Meanwhile the EU is considering a range of options including a ban on sending civilian technology used in the IT or cyber-security sectors to Russia among other trade restrictions (assessed at €7 billion), as well as enhancing financial restrictions. At the same time, on 19 September the European Commission issued guidelines easing some previously-imposed sanctions; these include allowing EU entities to transfer Russian coal and fertilisers to third countries (including via the EU), in order to ensure global food and energy security.

Commentary

- The pseudo-referendums on annexation were a complete sham, and had the character of a political demonstration supervised by Russian security forces. The voting process itself was organised to ensure preconceived ‘results’ that bore no relation to reality or the mood of the local population, which has been terrorised by the occupying forces. The ‘referendums’ were made into a propaganda spectacle to convince the Russian public that the inhabitants of the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine ‘genuinely wished to be incorporated into Russia’, and that the ‘special military operation’ had been launched by Moscow for humanitarian reasons, and had ended in success.

- The formal annexation to Russia of the territories covered by the ‘referendums’ is expected in the coming days. The documents on this matter (the so-called international agreements and the federal constitutional law increasing the number of subjects of the Russian Federation) must be approved by both houses of parliament (the National Assembly). This can be fast-tracked at any time. Statements by Federation Council head Valentina Matviyenko and State Duma chairman Vyacheslav Volodin indicate that parliament is expected to meet on 3 and/or 4 October. Media reports suggest that the Kremlin may establish a new, ninth federal district covering the annexed areas including Crimea.

- In Moscow’s intention, the annexation of the occupied areas will allow it to promote the thesis that Ukraine is attacking territory which comes under Russia’s ‘nuclear umbrella’, so Kyiv should be forced to cease its offensive actions. So far, however, the Ukrainian military has remained unaffected by the threat to escalate the conflict. The Russian forces are now in defensive positions, and will not be able to quickly adjust the front line in their favour in the near future. Moreover, annexation does not guarantee the stabilisation of the situation in the occupied territories. The obedience of the local population will be enforced by repression, and its morale will further deteriorate with the start of mobilisation for the Russian army. This process is expected to begin in the occupied territories once the procedures for their annexation to the Russian Federation have been completed.

- The annexation will further radicalise anti-Russian attitudes in Ukraine. It will not have any negative impact on the motivation of the troops there to continue fighting, and it will stiffen Kyiv’s position regarding any possible peace talks. The annexed areas will continue to be hit by acts of sabotage. The annexation will make it easier for Kyiv to intensify its accusations that Russia is a waging a war of aggression, to lobby for its recognition as a terrorist state, and to seek further arms supplies and the imposition of further sanctions from the international community.

- It is to be expected that the vast majority of the Russian public will welcome the ‘reunification’ of the occupied lands with Russia. According to a poll by the independent Levada Centre published at the beginning of September (which, under conditions of war and wartime censorship, should be treated with due caution), 45% of Russians supported the entry of the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts into the Russian Federation, 21% thought they should be independent states, and only 14% said they should be left within Ukraine’s borders. In February this year (before the invasion began), 33% of Russians were in favour of the independence of the so-called DPR and LPR, 25% in favour of their entry into the Russian Federation and 17% in favour of autonomy within Ukraine.

- By holding these pseudo-referendums, the Russian Federation has brutally violated the principles of international law. Both the West’s refusal to recognise the impending annexation of the occupied territories to Russia and the announcement of new sanctions are in line with its previous actions in support of Ukraine. The unequivocal declarations by countries hitherto perceived as being pro-Moscow (such as Serbia and Kazakhstan) not to accept the results of the ‘plebiscite’, and the failure of any country to announce recognition of the Kremlin’s planned annexation, will further deepen Russia’s isolation.

- The initial announcements of new restrictions against Russia suggest a rather limited response from the West. During the seven months of the war, Western countries have already managed to impose sanctions on most sectors of the Russian economy. However, the bans on iron and coal imports to the EU only came into force in the summer, and a significant part of the restrictions (such as the ban on technology exports to Russia) will affect Russia gradually, and their effects will only become apparent in the long term. Moreover, the sanctions that are crucial from the perspective of the Russian budget – the embargo on imports of oil and petroleum products to the EU – will take effect in late 2022 and early 2023. In turn, the easing of some restrictions may reinforce the Kremlin’s belief that the West is losing its ability to take concerted steps to harm Russia. In particular, the European Commission’s decision to limit sanctions on the supply of Russian coal to third countries will make it much easier for Russian exporters to reach alternative customers. At the same time, it poses the risk of circumventing the restrictions, as the coal destined for third countries might be transferred via EU territory.

Map. Pseudo-referendums in the occupied territories

Source: authors’ own research.