Further restrictions on Russian oil exports

On 5 February 2023, the European Council decisions came into effect regarding the embargo on the import of Russian petroleum products to the EU and the introduction of a price cap on selling these products to third countries. The limit has been set at $100 per barrel in the case of lighter (more refined) types of products such as diesel and kerosene, which are sold at a premium to crude, and at $45 per barrel in the case of heavier types such as fuel oil. This means that European companies will continue to be allowed to carry out maritime transport of petroleum products from Russia to third countries at contract prices that do not exceed the price cap specified above, and to provide all types of services related to such transport (including technical assistance, brokering and financial services). These services should have been fully banned, in line with the sixth package of EU sanctions against Russia adopted in June 2022. Alongside this, a transitional period of 55 days during which the price cap will not be applicable was introduced for vessels carrying Russian petroleum products which have been purchased and loaded prior to 5 February 2023 and will be unloaded by 1 April 2023.

The price cap has been agreed in close cooperation with all the G7 states and Australia. Similar restrictions, including a ban on imports and a price cap, have been in place since 5 December 2022 in relation to Russian crude oil. The Price Cap Coalition has announced that it will review the current price cap for crude oil (which at present stands at $60 per barrel) in mid-March 2023.

Commentary

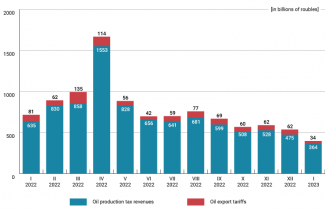

- The decision to set the price cap on Russian crude oil and petroleum products was intended to prevent the global market from destabilising and to avoid a sudden increase in the prices of these products in connection with the EU embargo. As a consequence, Russia’s budget revenues were expected to shrink. The first economic reports since the introduction of the embargo and the price cap indicate that these initial goals have been attained. Since the beginning of December 2022, global oil prices have remained unchanged (a barrel of Brent oil costs $80–85, around $20 less than in August 2022), while according to the Russian finance ministry in January 2023 the average price of Russian Urals oil was less than $50 per barrel, more than 40% lower than in January 2022, and the lowest price since December 2020. As a result, in January 2023 Russia’s oil revenues shrank by almost 44% y/y (see Chart), and the government had to use the reserves of the National Welfare Fund (NWF) to offset a budget gap of nearly $55 billion. According to Russian forecasts, in February 2023 the oil and gas revenues earned by the state budget may be lower by another 108 billion roubles. If the price of Urals oil continues at $50 per barrel, the deficit may rise by 2 trillion roubles up to 5 trillion roubles (the equivalent of $70 billion at the current exchange rate), because it was calculated on the assumption that the average oil price would be $70 per barrel.

- Despite Russia’s shrinking budget revenues (in January 2023 the total revenue was less than 1.4 trillion roubles, 35% less than in January 2022), the government is still dynamically boosting spending. In January 2023 it spent more than 3.1 trillion roubles, almost 60% more than in January 2022; that is more than 10% of the expenditure planned for 2023 as a whole. This suggests that the deficit may further increase. Although the current reserves and the petrodollars earned in 2022 should enable the Kremlin to cover the state’s expenditure in 2023, maintaining such a high spending level in the coming years will pose a major challenge to Russia. For example, at the end of December 2022 the value of the NWF’s liquid assets stood at 6.1 trillion roubles. Moreover, the burden placed on business, and in particular the energy sector, has been on the rise. The government has also announced that starting from 1 March 2023 it will change the methodology for defining the average price of Urals oil, which forms the basis for taxing oil companies. Reports suggest that the government intends to regulate this price to a large degree (at present it is based on market calculation made by the Argus agency). This, in turn, may further increase the costs borne by the oil sector.

- So far, Russian oil companies have not experienced the full impact of the Western restrictions imposed on them. Most importantly, oil supplies carried out via pipelines are still excluded from the EU’s embargo on oil imports (as this is how oil is supplied to Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary). The same applies to the maritime transport of oil to Bulgaria. Furthermore, because of the high oil prices recorded in the first half of 2022 Russian oil companies made major profits, and that in turn offset the lower price levels recorded at the end of the year. For the time being, Russia is maintaining its high oil production level (which actually increased by 2% in 2022, up to 535 million tonnes). Its crude oil was mainly transported to India, China and Turkey. Prior to 5 February 2023, Russian petroleum products (mainly diesel) were mainly sold in large amounts to EU member states, which then attempted to stockpile them ahead of the sanctions coming into effect. In addition, Russian companies increased their supplies of these products to African states and Turkey.

- According to Russian statistics, in 2021 Russia exported more than 144 million tonnes of petroleum products (“premium-to-crude” products accounted for around 60% of this volume), around 60% of which were sent to the EU (less than 15% of the bloc’s demand). The ban on supplies of Russian petroleum products to the EU market may pose a serious problem to Russia because there are numerous barriers to finding alternative markets to sell them on. Most importantly, the logistics involved is complicated (many small tankers need to be used, because light products must not be loaded onto vessels which previously transported fuel oil due to the risk of contamination etc.), and that makes transporting them long distances hardly profitable. Another challenge will involve finding new customers. The Asian market, on which the Kremlin is pinning its hopes, is characterised by strong competition, so it is unlikely that its biggest actors (China and India) will permit Russia to sell its diesel and gasoline on it, and supplying fuel oil to this market may prove unprofitable. Africa and Turkey will most likely be unable to buy all the Russian exports. This means that Russia will make attempts to increase its crude oil supplies to non-Western states, from which petroleum products will be sold to Europe. This is how oil companies will try to reduce their production decline (which is forecast at 5–7% in 2023). However, this will affect Russian refineries: for example it is estimated that the production of diesel will shrink by around 12%. In addition, most of these facilities have not been modernised, and continue to produce large amounts of low-quality products which will be difficult to sell.

- There is no doubt that Russian companies will attempt to circumvent Western sanctions. Numerous journalistic investigations have revealed that they are using a ‘shadow’ tanker fleet for this purpose (its owners are not known); they conceal the products’ origin by hiring numerous middlemen, blend various types of oil, and trans-ship it on the open sea. It is likely that as a result of this practice a portion of Russian oil does reach Western states, or it is trans-shipped in collaboration with European companies even if the price cap is exceeded. The Russian budget statistics indicate that the sanctions are not being evaded on a large scale, because these mechanisms increase the cost of supplies and result in customers demanding bigger discounts. That in turn reduces Moscow’s revenues, but generates profits for the middlemen.

Chart. Russian state budget’s oil revenues

Source: Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation.