The game has new rules. Amendment to the electoral law for the Bundestag

On 17 March, the Bundestag passed an amendment to the electoral law which provides for a reduction in the number of its deputies, from 736 at present to 630 after the 2025 elections. The main element of the reform will lead to the abandonment of the allocation of so-called surplus and compensatory seats. The number of these seats varies; it currently stands at 138 (see ‘Za duży Bundestag: spór o reformę prawa wyborczego’). The second element of the amendment is the abolition of the basic mandate clause, which entitles a party that has not crossed the 5 percent electoral threshold but has won at least three direct seats to enter the Bundestag. In the current term this clause was used by Die Linke, which won only 4.9 percent of the vote in the federal elections, but was able to form a parliamentary grouping of 39 members in the Bundestag as it won three direct seats. A simple majority in the Bundestag is sufficient to change the electoral law, and the Bundesrat has no veto power over the issue. In reaction to the adoption of the amendment, the CDU/CSU and Die Linke announced that they would file a complaint with the Federal Constitutional Court (FTK).

The Bundestag is the largest democratically elected parliament in the world, employing some 7000 people in its service. Its annual expenditures amount to €1 billion (2020), and have risen by around 32% since 2016. The accommodation for the parliament is becoming increasingly challenging: it is getting harder to provide offices for parliamentarians, rooms for committee meetings, and expand the size of the plenary chamber.

Commentary

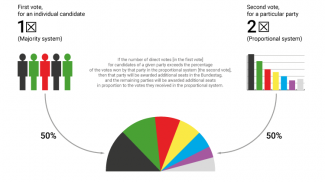

- Under both the existing (see chart) and the new systems, each German voter has two votes in federal elections. The first vote goes to the candidate from the voter’s regional district (of which there are 299 in total); the candidate who receives the most support in a district enters the Bundestag. A further 299 MPs are elected by voting for party lists in the individual state (this is the second vote). This determines the strength of the parties represented in the Bundestag, as the votes received are converted into seats in parliament. Since some parties win more seats under the first vote than the second would have given them, in the present system additional deputies are allocated to them, to maintain the correct ratio of seats each party has won. This practice brought about the increase in the Bundestag’s size. The new amendment to the law changes this; under the new rules, not all the candidates elected under the first vote will enter the Bundestag if their party won fewer seats under the second vote.

- Changing the ordinance was one of the current coalition’s most important domestic election promises, and it was planned for in the coalition agreement. Its passage and implementation are intended to demonstrate the effectiveness and unity of the ruling parties, especially in the light of their increasingly apparent internal disputes and the decline in their popular support. The determination to carry out this reform indicates that even in the face of war and the consequent focus on foreign and defence policy, domestic issues remain important to the SPD, Greens and FDP.

- The reform was necessitated by the increase in the number of deputies over successive terms, and has been the subject of fierce political dispute over recent years. Until now, initiatives to reduce the number have met resistance, especially from the CSU, which has benefited most from the current rules. This party, which runs exclusively in Bavaria, wins the direct seats in an overwhelming number of districts. So far, this has guaranteed the CSU’s presence in the Bundestag regardless of the party’s declining support (it won only 5.2% of the vote in 2021).

- The amendment in its current form threatens the two smallest groups, Die Linke and the CSU. At the federal level, both parties are balancing on the verge of the electoral threshold, and could find themselves outside parliament after the new law is introduced. In an extreme situation, this would mean that only four parties would enter the Bundestag: the CDU, SPD, the Greens and AfD (the FDP is also hovering around 5% support in the polls, and has not entered the regional parliaments in the last two elections). This would permanently weaken the position of the Christian Democrats, whose support would drop by several percentage points (as they form a joint parliamentary club with the CSU). It would also likely force the CDU, SPD and Greens to build a coalition against the only opposition party, the AfD. One way to avoid such a scenario could be the creation of a joint CDU/CSU list in Bavaria, but neither the current nor the amended law provides for this possibility. In the long term, this would result in the CSU being marginalised to a regional grouping, becoming just one of the CDU’s sixteen regional structure – a scenario that the CSU has always wanted to avoid (see The free state of Bavaria: The end of the CSU’s sovereign duchy?).

- The amendment was passed solely with the votes of the coalition members, who did not seek to come to an agreement with the opposition. This undermines the specificity of the German political system, which has been built up over many years on the basis of a culture of compromise. The need to seek consensus between the parties has so far been treated as a sine qua non for any far-reaching reform of the law (hence its earlier failure, due to the veto of the CSU). There had been no mention in earlier plans of such a radical change which would remove the basic mandate clause, striking directly at the coalition's political opponents. It is not clear to what extent this amendment represents a form of ‘payback’ for the years of obstructionism in parliamentary work on the issue, and to what extent it is a way for the ruling coalition to put pressure on the Christian Democrats to engage in further reform talks. This is evidenced by the proposals which coalition politicians have put forward to the CSU for further changes which would allow the formation of joint party lists with the CDU.

- The electoral law reform raises fundamental constitutional questions. These primarily concern the abolition of the principle of automatic entry into the Bundestag for deputies elected from a direct list, thereby undermining the principle of equal voting. In addition, a 1997 judgement by the FTK confirmed the constitutionality of the basic mandate clause. Nor has it yet been determined which law will be the basis for the elections to be held in 2025; that depends on the final decision of the Court, and it is not yet clear when it will make its final judgement. The debate also raises the political argument of failing to take the country’s traditional regional differences into account, by making it more difficult for the CSU and Die Linke (which is represented more strongly in Germany’s east) to enter the Bundestag. Both parties will use the amendment as an argument to hit back at the federal government during their campaigns in regional elections – the CSU in Bavaria this October, and Die Linke in Thuringia (where the party is in power), Brandenburg and Saxony in the autumn of 2024.

Chart. The existing electoral system – the national list and direct seats

Source: author’s research, based on Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, bpb.de.