Dispute over funding refugees’ residence in Germany

During a meeting between Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the prime ministers of the Bundesländer in Berlin on 10 May, it was agreed to raise the earmarked subsidy to cover part of the expenses related to refugee policy by €1 billion, to €3.75 billion. However, no agreement was reached on a permanent mechanism for sharing these costs between the states and the federation. The states are demanding that the central budget support be adjusted to the number of asylum seekers in Germany on a per capita subsidy basis.

In the German federal system, most of the costs of housing and integrating refugees are borne by the individual states. However, the federal budget co-funds social benefits (to the tune of €8 billion in 2022), integration courses (€2.3 billion) and combating the causes of migration (€12 billion).

The meeting announced measures to curb illegal migration on two levels, the European and the German federal. In the first case, the German government advocates sealing the EU’s external borders and establishing centres to register refugees there. Some asylum applications would be processed on the spot, and those without the right to stay in the EU would be deported to their countries of origin. This procedure is to be complemented by a ‘solidarity mechanism’, allowing refugees to be distributed among member states. Other elements intended to reduce the number of illegals entering Germany include their more effective deportation from the country and the expansion of the list of so-called safe countries of origin to include Moldova and Georgia (which has hitherto been impossible due to opposition from the Greens). The announced digitisation of the administration’s workflow is also expected to speed up the asylum procedure; at present, a single application takes about seven months on average to process.

Support for accepting refugees from war remains very high in Germany (84%, according to a survey by Infratest dimap for ARD TV on 4 May). At the same time, the vast majority of Germans (77%, regardless of party sympathies) believe that politicians take too little interest in the problems caused by immigration. In addition, 54% are convinced that the phenomenon has more negative than positive consequences for their country. This position is most often represented by supporters of the AfD (95%) and the CDU/CSU (59%), whereas supporters of the Greens primarily see migration as having positive results (68%). At the same time, 41% of respondents would like to see an increase in labour migration to Germany, while 28% would like to see it maintained at its current level.

Commentary

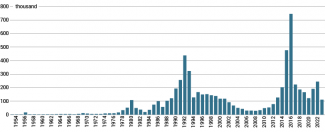

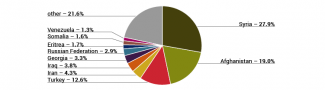

- The burden on local governments caused by the surge in asylum applications and the influx of refugees from Ukraine is the highest since the 2015 migration crisis, and it will only continue to grow. More than 100,000 such applications have been filed in Germany since the beginning of the year, 78% more than in 2022. The most frequent asylum seekers come from Syria (28,000, up 73% y/y), Afghanistan (19,000, 83% up) and Turkey, from where the number of applications is rising fastest (12,000, up 259%). A significant number of these people arrive from Greece and Italy. However, Germany does not send refugees back to these countries (as the Dublin III regulation would theoretically allow them to). This is due to Italy’s refusal to accept them due to the overcrowding of the centres and the state of emergency there, as well as the rulings by German courts, which consider the living conditions in the centres in Greece to be substandard.

- It will be very difficult to implement most of the proposed changes to curb migration, and so there will not be a rapid and sustained reduction in the number of people entering Germany illegally. Many of these demands (such as speeding up the deportations and processing a certain percentage of the applications at the EU’s borders) have been debated for many years; however, past experience both in Germany and at the EU level indicates the difficulty of pushing them through. In addition, the increase in targeted funding for the Länder, while desirable, will not solve a number of the systemic problems local governments have been experiencing related to refugee care. These increasingly concern the overcrowding of refugee centres and of schools, as well as the shortage of teachers, and problems connected with integrating the new arrivals. The issues of paying for the refugees and curbing illegal immigration to Germany will be the topics of Chancellor Scholz’s further meetings with the prime ministers of the Länder: the next one is scheduled for June.

- There is an ongoing dispute within the ruling coalition over what specific solutions for Germany’s migration policy can be found; hence some of the proposals have been formulated in more general terms, and will need to be clarified in the coming months. The SPD, and especially the FDP, have advocated a more restrictive approach to the protection of the EU’s external borders and the deportation of people without the right to stay in Germany. The Greens lean toward more liberal solutions, including refusing to classify some North African countries as safe countries of origin. However, given the very difficult situation which the local governments governed by the Greens also find themselves in, an internal party debate about tightening migration policy is also taking place; for example, chairman Omid Nouripour has called for a strict defence of the EU’s external borders. Meanwhile, however, every member party of the coalition has advocated increased labour migration to Germany to narrow the labour market gap. The Institute for Employment Research (IAB) estimates that due to demographic changes, the demand for workers in Germany will increase to 7 million people by 2035.

- Prior to the meeting, the state interior ministers of Brandenburg and Saxony (both from the CDU) had demanded the establishment of points on the borders with Poland and the Czech Republic to carry out random checks, similar to those on the border with Austria, which have been in place since 2015. The findings after the summit indicated that such additional controls could be introduced, depending on how the border situation develops. So far, such steps have been opposed by the federal interior minister Nancy Faeser. However, this decision may be forced to change out of fear of a rise in support for the anti-immigrant AfD. Limiting migration is the most important topic for this party, and voters believe that it has the highest competence in this area after the CDU and SPD (as shown in the above-mentioned Infratest dimap poll for ARD). In recent weeks, the party’s popularity has stabilised at 16% (it won 10% in the Bundestag elections), and in some polls it places third behind the CDU and SPD. The AfD is particularly strong in the eastern states (Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia), where elections for state parliaments will be held next year. According to the survey, it is currently in the lead in these states, with support of 23% and 28% (in Saxony and Thuringia) each respectively. This will push the Christian Democrats (their main rivals in the region) to ramp up their anti-immigrant rhetoric, in the hope of retaining power in Saxony and winning in Brandenburg and Thuringia.

Chart 1. Number of asylum applications in Germany since 1953

Source: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

Chart 2. Origin country of asylum seekers in Germany between January and April 2023

Source: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).