Victory for the Christian Democrats and success for the AfD in Hesse and Bavaria

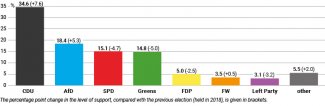

In the elections to the Landtags of the German federal states of Hesse and Bavaria, held on 8 October 2023, the Christian Democratic parties, that is the CDU and the CSU, came first. In Hesse, the ruling CDU won 34.6% of the votes (+7.6 percentage points compared with 2018), which translates into 52 seats in the 133-seat local parliament (see Chart 1). The turnout was 66%, slightly lower (by 1 percentage point) than in 2018. Minister-President Boris Rhein can now continue his coalition with the Greens or decide to form an alliance with the SPD. The former option is considered more likely, including due to a positive history of cooperation thus far.

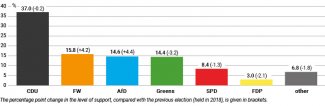

In Bavaria, the CSU, which has ruled this state since 1957, garnered 37% of the votes (-0.2 percentage points compared with the 2018 election), which will translate into 85 seats in the 203-seat Landtag. Its current coalition partner, the Free Voters (Freie Wähler, FW), has improved its result by 4.2 percentage points and won 15.8% of the votes, which will give it 37 seats (see Chart 2). The turnout was 73% (-1 percentage point). During the campaign, Bavaria’s minister-president and CSU head Markus Söder supported the plan to continue the coalition with the FW. Other possible options may include an alliance with the Greens (which the CSU chief previously ruled out) and with the SPD. Neither in Hesse, nor in Bavaria do the Christian Democrats intend to enter into coalition with the AfD.

Commentary

- The victory of the Christian Democrats in both federal states mainly results from voters’ opposition to the rule of Chancellor Olaf Scholz. The Christian Democratic parties openly encouraged the public to treat the recent elections as a referendum on the federal government, and the most important topics discussed during the campaign included migration and Germany’s declining economic situation (see ‘The Meseberg arrangements: the German government is tackling the crisis’). In both federal states, more than 50% of the respondents said that the election was an opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with the government in Berlin (the poll was conducted on 8 October by the Infratest dimap polling company for the ARD). In addition, the SPD’s campaign in Hesse was incoherent and contained numerous mistakes, and the main candidate, Germany’s interior minister Nancy Faeser, announced before the election that in case she is not elected, she will remain in Berlin as a member of the federal government, which the voters reacted to with little enthusiasm. Faeser’s electoral failure has weakened her position in the Scholz cabinet and, in the context of the negotiations within the coalition regarding changes to Berlin’s migration policy, she will be an increasing burden to Chancellor Scholz.

- Rhein’s very good result has boosted his position within the CDU and has transformed him into one of Friedrich Merz’s potential rivals in the competition for the Christian Democratic parties’ nominee as prospective chancellor candidate ahead of the federal elections in 2025. Merz’s other possible rivals include Hendrik Wüst, the minister-president of North Rhine-Westphalia, and Daniel Günther, the head of the state government of Schleswig-Holstein. Just like Wüst and Günther, Rhein supports a different vision of the CDU than the one endorsed by Merz. According to them, the party should be more liberal (for example as regards migration issues) and ready to form a ruling coalition with the Greens, modelled on the coalitions which govern their federal states, which they head. The result obtained by the CSU is viewed as moderate but at the same time as one that poses no threat to Söder. The Christian Democrats owe their high level of support to positive opinions regarding the rule of these federal states’ minister-presidents and to their popularity, especially against the backdrop of their rivals. In addition, for most voters migration was the most important topic of the campaign (in Bavaria 83% of respondents support the plan to curb it), and the minister-presidents of both federal states have blamed Chancellor Scholz for the migration crisis.

- The AfD’s success in Hesse and Bavaria has enabled it to distance itself from its image as a ‘party of protest from the east’. The party has now obtained the highest result in its history in the western German federal states (its previous highest result was 15% obtained in Baden-Württemberg back in 2016) and most likely will become the biggest opposition party in these two federal states. In Bavaria, the AfD’s voters included 80,000 former supporters of the CSU and 40,000 liberals. In addition, the party has managed to activate 80,000 non-voters (in Hesse 46,000 of its voters were former non-voters and 29,000 SPD supporters).

- The AfD’s result reflects its level of support in Germany as a whole, which is around 21–22%. Among the main reasons behind their decision to vote for the AfD, the respondents cited their support for this party’s platform (47%, +9 percentage points compared with 2018) and their positive assessment of the competences of the party’s activists. This mainly involves migration policy and domestic security, as well as various issues linked with social justice. The AfD’s opposition to the federal government in Berlin continues to be an important factor for their voters and many of them have pinned their hopes on this party to be an initiator of change (see ‘Too green, too fast, too dear. The AfD is gaining popularity in Germany’). Furthermore, 85% of Bavarians admit that instances of right extremism within the AfD are of no decisive importance to them, as long as “[the party] raises appropriate issues in the public debate”. The AfD’s rich vein of results will most likely continue in the elections to the European Parliament (EP) and in local elections in the eastern German states.

- The election was a success for the FW. Due to his decision to focus his campaign predominantly on the policy pursued by the government in Berlin and on demands calling for curbing migration, Hubert Aiwanger, the party’s charismatic leader in Bavaria, has managed to convince numerous former supporters of all parties except for the AfD (including 140,000 CDU supporters) to vote for him. The level of support for his party has not changed following the so-called ‘Aiwanger scandal’ in which he was accused of distributing anti-Semitic leaflets when he was 17 and of other irregularities. The FW has co-ruled Bavaria since 2018 and has been represented in the EP (two MEPs since 2014) and in the local parliament of Rhineland-Palatinate (it obtained 5.4% of the votes in the most recent election). In addition, in Saxony and Hesse the party’s level of support is around 3%. Following its electoral success in Bavaria, the party intends to enter politics at the federal level. Coordination of the party structures in specific federal states will pose a major challenge to the FW, as in each state the party has established an independent association of electoral committees. Due to divergent regional ambitions, this party has no nationwide structure. Some committees are grouped in the Federal Association of Free Voters’ Communities (Bundesverband der Freien Wählergemeinschaften), which is headed by Aiwanger. In the recent election to the Bundestag, the FW obtained 2.4% of the votes, which has enabled it to become the strongest non-parliamentary opposition party. Its basic platform focuses on local-level politics including the proposal to hold referendums on as many issues as possible, the defence of traditional agriculture (the FW enjoys a high level of support in rural areas), a conservative outlook on life and economic liberalism.

- The Greens have suffered a major defeat, especially as regards their aspirations to have their candidate assume the office of the minister-president of Hesse. Their electoral result, which in both states was below expectations, was mainly due to the general decline in the party’s level of support nationwide and to the federal dispute over migration policy. Other reasons included criticism of their poorly prepared and adopted heating law (see ‘Germany: a controversial heating law’). The largest group of voters who are disappointed with the Greens’ policy in Hesse this time supported the CDU (this group includes 57,000 individuals, who in previous elections voted for the Greens).

- For the FDP, their defeat in Bavaria means that they will not be represented in the third consecutive Landtagsince their entry to the government in Berlin as a ruling coalition partner. At present, the position of the party’s head Christian Lindner is not challenged (including due to the lack of clear rivals). However, the party’s likely poor result in the 2024 election and the prospect of federal elections in 2025 may spur the FDP to act more assertively within the coalition.

- The defeat of the parties which co-form the federal government will increase the already present tensions affecting it. Each party will attempt to emphasise its separate stance, especially in those areas in which their views are most divergent (for example in issues relating to migration, asylum and climate). These activities are likely to intensify ahead of the election to the EP in May 2024 and to the Landtags in autumn 2024. If the trends which are already evident in polls conducted in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg are maintained (the AfD is leading with more than 30% of voter support in each of these federal states), the coalition parties will suffer a series of major defeats. This, in turn, will amplify the voices calling for bringing Chancellor Scholz to account for his ineffective policy.

Chart 1. Results of the Landtag election in Hesse held on 8 October

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures published by the electoral committee in Hesse, wahlen.hessen.de.

Chart 2. Results of the Landtag election in Bavaria held on 8 October

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures published by the electoral committee in Bavaria, statistik.bayern.de.

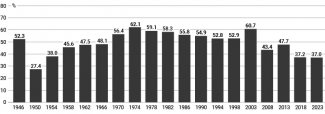

Chart 3. The CSU’s results obtained in Bavaria’s Landtag elections since 1946

Source: author’s own analysis based on wahlrecht.de.