Russian missile terror. Day 678 of the war

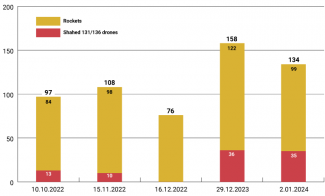

Between 29 December and 2 January, Russia launched numerous missile strikes on targets across Ukrainian territory. 29 December saw the largest missile and kamikaze drone attack since February 2022 (see Appendix). According to the Ukrainian army’s Commander-in-Chief General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the invaders used at least 158 means of aerial attack that day: 122 ballistic and cruise missiles (the Ukrainian General Staff report increased this number to 150 on 30 December) and 36 Shahed drones. The defenders claimed to have shot down 87 Kh-101/Kh-555/Kh-55 cruise missiles, out of at least 90 which the Russians launched, as well as 27 Shahed 131/136 drones. The invaders also used eight Kh-22/Kh-32 cruise missiles, at least 14 Iskander-M and 9M82/9M83 ballistic missiles fired from S-300 systems, five Kh-47M2 Kinzhal hypersonic missiles, four Kh-31P anti-radiation missiles and one Kh-59 air-to-ground missile. Zaluzhnyi said critical infrastructure, industrial and military facilities were targeted. There were also many civilian casualties (53 people were killed and 170 injured) and damage to residential, health and education facilities.

The capital Kyiv was particularly seriously affected: one of the targets was most likely the Artem factory near Lukyanivska metro station, the damage to which was widely publicised by Ukrainian media. Destruction was also reported in four other districts of the city. By 3 January, the death toll from the attack in Kyiv had risen to 30, making it the bloodiest Russian strike on the Ukrainian capital since the launch of this phase of the war in February 2022. In addition, attacks were launched on Odesa (five fatalities), where the main target was the port infrastructure; Lviv (one civilian killed), where weapons repair facilities were hit; Kharkiv (three fatalities), where the Russian missiles’ targets included the Malyshev armour repair plant; Konotop in Sumy oblast; the city of Dnipro where (seven civilians killed) and the neighbouring town of Novomoskovsk; and Zaporizhzhia city (nine fatalities), where the targets included the Iskra factory. Infrastructure facilities were also reported to have been hit in Selydove in Donetsk oblast, and Drohobych near Lviv. The Russians launched another attack in the afternoon of 29 December, hitting targets with rockets in Sumy city and Cherkasy oblast (one person was killed in the latter area).

During the night of 30 December, Russian kamikaze drones struck Kherson and Khmelnytskyi oblasts (the Ukrainian General Staff reported that five of the 10 Shaheds used by the invaders had been shot down); Iskander-M and Kh-59 missiles struck Zaporizhzhia and Odesa cities during the daytime. The Ukrainian side also claimed to have downed one Kh-59 missile fired at Dnipro city. In the evening, at least six rockets (depending on sources, they were either Iskanders or fired from S-300 systems) hit Kharkiv, including the Kharkiv Palace hotel often used by foreign visitors. Twenty-two people were injured. Selydove in Donetsk oblast was also targeted again. According to the General Staff, the invaders used a total of nine missiles.

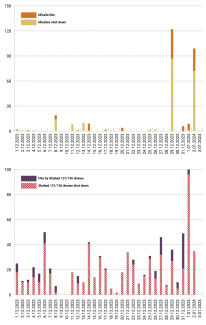

On 31 December, the Russians used the largest number of kamikaze drones to date: according to a communiqué from the Ukrainian General Staff, 96 during the day, and 49 in one night attack alone, as reported by the Air Force Command. The defenders claimed to have shot down a total of 66 Shaheds (21 during the night attack). Russian drones hit Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv cities, and the Mykolaiv, Odesa, Kyiv and Khmelnytskyi oblasts in turn. Meanwhile 13 missiles targeted Kropyvnytskyi (here, most likely hypersonic Kinzhal missiles) and Chuhuiv in Kharkiv oblast.

Another major kamikaze drone attack occurred on the night of 1 January, although the number of drones used is far from clear. According to the Ukrainian General Staff, the Russians used 26 drones of which 21 were shot down, while the Air Force Command claims as many as 90 drones were used, of which the defenders destroyed 87. It cannot be ruled out that the second source combined the information about the attacks on the evening of 31 December and the night of 1 January; but even then there would be a discrepancy, as the total number according to the General Staff’s statements would be 73 (of which 66 were reportedly shot down). On the other hand, according to the head of the press centre of the so-called ‘Defence Forces of the South’, Natalia Humeniuk, in the attack on southern Ukraine from 31 December to 1 January, the defenders destroyed 50 of the 60 Shaheds used by the aggressor (including 30 in Odesa oblast). Damage as a result of the drone strikes was reported from Odesa (the port infrastructure was hit and one person was killed), Lviv (the shockwave led to damage to buildings in Dublany; the local authorities reported the destruction of the UPA commander Roman Shukhevych’s museum in the Bilohorshcha district of Lviv) and Dnipro (where an industrial facility was hit). In turn, the attacks reported in Khmelnytskyi and Kyiv oblasts were repulsed. In the afternoon, the Air Force Command reported another strike using 10 Shahed 131/136 drones, nine of which the defenders shot down.

On 2 January, the Russians launched another massive attack in which they used 99 ballistic and cruise missiles and 35 kamikaze drones, according to General Zaluzhnyi. According to the Air Force Command’s communiqué, 72 missiles were shot down: 59 of the 70 Kh-101/Kh-555/Kh-55 cruise missiles and all three of the Kalibrs used by the invaders, all 10 Kinzhals and all 35 Shahed 131/136 drones. In addition, the Russians used 12 ballistic missiles from Iskander-M and S-300 systems, and four Kh-31P anti-radiation missiles. Zaluzhnyi resorted to a different kind of messaging compared to 29 December; this time he reported that civilian and critical infrastructure facilities as well as industrial and military facilities had been attacked. These strikes left five civilians dead and 127 injured.

The main target was once again Kyiv, where significant damage was caused to the Mayak, Radiovyzmiruvach and Kvazar industrial plants. Damage of varying degrees was reported in nine areas of the city, with two civilians killed and 50 injured. Unlike previous attacks, there was widespread damage to the power grid in Kyiv and the oblast, resulting in 259,000 users being cut off from electricity in the city and a further 184,000 in the region as a whole. However, major energy infrastructure facilities were not attacked (most of the damage was caused by falling debris), allowing power supplies to be restored in less than a day. In addition to Kyiv, Russian missiles struck Kropyvnytskyi and Kharkiv. In the latter, one person was killed and 50 injured, and missiles from S-300 systems struck Kharkiv again late in the evening of 2 January.

On 30 December, Ukrainian forces carried out a massive attack on Russian territory and facilities in the occupied part of Ukraine, which was described as retaliation for the Russian strike 24 hours earlier. The Russian side reported that it had downed 32 kamikaze drones over the Bryansk, Kursk, Moscow and Oryol oblasts, as well as a surface drone off the Sevastopol roadstead. According to some Ukrainian media, the defenders used a total of 70 drones in the attack, but there are no reports on the results. In the early afternoon the city of Belgorod, located 30–40 km from the border (depending on the measurement point), was attacked from multiple rocket launchers (according to Russian sources, these were Ukrainian Vilkhas, based on the Soviet BM-30 Smerch, and RM-70 Vampires received from the Czech Republic). Military facilities were the most likely target, although the Ukrainian missiles also struck the civilian centre of the city. According to Russian data from 1 January, 25 people were killed and 131 wounded. Civilian casualties (four dead and 13 wounded) were also reported as a result of the Ukrainian shelling of Russian-occupied Donetsk city. The strikes on Belgorod were repeated on 2 and 3 January. Sevastopol and the Kursk oblast, where a power substation was damaged, were also to be targets of attacks on 3 January.

The Russians made slight advances to the north and south-west of Bakhmut (the main combat zone is Bohdanivka, which flanks Chasiv Yar from the north-east), to the south-east of Siversk (according to some sources, the invading troops have outflanked the defenders in the village of Vesele) and to the north and north-west of Avdiivka. The situation in the other directions has not significantly changed. The intensity of the fighting decreased over the New Year period, but according to the Ukrainian General Staff, the Russians are still launching over 50 assaults a day on Ukrainian positions. On 3 January the commander of the Ukrainian Land Forces, General Oleksandr Syrskyi, said that Kupyansk and Bakhmut were the areas with the highest intensity of fighting.

On 2 January the head of the Ukrainian foreign ministry, Dmytro Kuleba, stated that he was waiting for decisive action from Western countries after another massive Russian missile attack. As he put it, there are five steps that Ukraine’s partners could take at the moment: accelerate the delivery of additional air defence systems and ammunition; ensure the continued delivery of combat drones of all types; hand over missiles with a range of more than 300 km; agree to use frozen Russian financial assets to help Ukraine; and isolate Russian diplomats in Western capitals and international organisations.

On 29 December, the Ukrainian General Staff confirmed that hackers working for the army had attacked the servers of 53 Russian companies which support the invasion. Among their targets were the companies Metal Express (which specialises in the production of metal structures for the military-industrial complex) and TransAmur (which provides transportation for the armed forces).

On 29 December, the press service of Ukraine’s military intelligence service warned that the Russian special services were planning hybrid campaigns of sabotage and disinformation to discredit the military-political leadership. They will undermine the need for mobilisation, and encourage men to leave the country and avoid being drafted.

On 30 December, Ukrainian border service spokesman Andriy Demchenko admitted that checks on certificates allowing men to leave the country had been tightened. He stated that falsification of documents, e.g. confirming care of large families, was now widespread. In order to verify this, a system has been introduced whereby a military commission must issue an additional certificate allowing men to travel abroad.

On 31 December the head of the Kyiv City Military Administration, General Serhiy Popko, stated that although Kyiv is not part of the war zone, the strengthening of the capital’s defence capabilities has not been abandoned. In cooperation with the local authorities, military units stationed around Kyiv are systematically conducting training on how to prepare and conduct a possible defensive operation in the event of an enemy attack. Several defence lines of about 1000 km equipped with engineering barriers have been established around the city. Anti-aircraft and anti-tank defence positions are being prepared.

Commentary

- Contrary to the predictions of the Ukrainian government and the Western states supporting Kyiv, the main target of the Russians’ renewed missile attacks is not – at least so far – the energy infrastructure. It remains unclear whether Moscow has deemed the 2022 campaign to destroy Ukraine’s energy sector ineffective and abandoned it, or whether it will return to it in the future. The key targets of the recent strikes – which were the largest since the start of the war, in terms of the number of missiles and drones used simultaneously – have been Ukrainian army facilities. However, it is currently impossible to assess the impact of the attacks, let alone their effect on Ukraine’s defence capabilities. The main limitation is Kyiv’s information policy, according to which reporting the effects of hostile attacks is illegal and has been criminalised (despite this, the information blockade is not entirely airtight, as evidenced by the material available online which has confirmed the strikes on Kyiv’s arms industry facilities). The reports from the Russian side constitute a dubious alternative; even if they are true, they are undoubtedly part of Moscow’s wider information war.

- Despite the large scale of the Russian attacks during recent days, Ukrainian reports on the number of missiles and drones used by the enemy and the shootdowns claimed are questionable. Never before has there been such a wide discrepancy in Kyiv’s coverage as in its presentation of the impact of the attacks on the night of 31 December-1 January. It must be assumed each time that the number of shootdowns reported by the Air Force Command is inflated; this is a manifestation of the information policy of a state at war, especially one that is defending itself. Another problem is the reporting of the neutralisation of missiles, the destruction of which – even with the relatively modern Patriot systems – raises questions of a strictly technical nature. It cannot be ruled out that – as was the case with the Iskander-M ballistic missiles, the missiles from S-300 systems and the Kh-22/Kh-32 cruise missiles – the Ukrainian command will soon start reporting the shooting down of hypersonic Kinzhals (these reports have not been commented on by the American manufacturer of the Patriots). It should be emphasised that the reports of the Patriot systems’ extraordinary effectiveness is playing a significant role in boosting the morale of Ukrainian society. It also forms part of Kyiv’s pressure on its partners to provide more of the modern air defence systems which it needs for defence.

The text refers to the situation as of 6pm Central European time on 3 January.

APPENDIX

Chart 1. Top five Russian missile and drone attacks on Ukraine since 24 February 2022

Chart 2. Missile and drone attacks since 1 December 2023, and the effectiveness of Ukraine’s air defences

Source: authors’ own research based on communiqués from the Commander-in-Chief of the Ukrainian Army, the Air Force Command (DSP) and the General Staff (SG).

The chart shows the number of Shahed 131/136 strike drones used by the Russians, as well as cruise missiles (Kh-101/Kh-555/Kh-55, Kh-22/Kh-32, Kalibr, Iskander-K) and ballistic missiles (Iskander-Ms, 9M82/9M83s from S-300 systems, hypersonic Kh-47M2 Kinzhals). The invaders have also used small numbers of other air-to-ground missiles, mainly Kh-31P anti-radiation missiles, as part of its attack cover. In some cases, as the DSP and SG have updated data on the number of missiles used by the Russians, the number of missiles actually used by them may differ from the data reported in earlier war analyses given by us at the OSW.