Germany is making concessions over the reform of the EU’s fiscal rules

Shortly before the Christmas break, EU finance ministers agreed on the general guidelines for the reform of fiscal rules. First of all, more flexibility in reducing debt and the introduction of investment incentives is envisaged. This is a step towards making EU regulations more realistic and enhancing member states’ capabilities to better deal with the economic crisis and strategic challenges. The compromise became possible thanks to concessions by Germany. Olaf Scholz’s government had long been blocking progress in the negotiations because it was concerned about the consequences of loosening fiscal discipline and the politicisation of the fiscal sphere. However, its position has been weakening due to economic stagnation in the EU, as well as its own problems with maintaining budget discipline.

The framework of the member states’ budgetary policy has been determined for almost three decades by the so-called macroeconomic convergence criteria enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty and the Stability & Growth Pact (SGP). Despite numerous amendments to the system and its increasing complexity, its essence is still the EU countries’ obligation not to exceed the debt limit of 60% of GDP and the public deficit limit at 3% of GDP. If any of these limits is breached, the European Commission could initiate the so-called excessive deficit procedure and provide recommendations on fiscal policy. If a eurozone member state consistently fails to comply with the rules, it may (at least in theory) face financial sanctions.

In 2020, the restrictions were suspended due to the need to increase spending to fight the pandemic, and the suspension was further extended until 2024 due to the war in Ukraine and the energy shock. The break in the SGP has provoked a discussion on the purpose of retaining the present formula of the fiscal rules, and has mobilised advocates of reforms.

The fiscal deadlock

The dispute over the SGP has been ongoing for years. The ‘southern’ European countries and France have criticised it for being too rigorous, blocking necessary investments and its pro-cyclical nature, which forces savings in times of crisis and thus slows down economic recovery. Moreover, the disagreement within the EU over the creation of a large common fund to ensure ‘strategic sovereignty’ and investments, mainly due to resistance from Berlin, means that member states must have greater spending freedom.

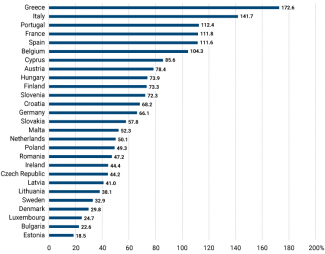

In turn, Germany and the ‘northern’ countries (including the ‘Frugal Four’, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden) have often complained about the discretionary nature of the Commission’s actions and the politicisation of the SGP, which actually prevented the imposition of financial sanctions on budget ‘sinners’ (see Back to discipline: How Germany views the reform of EU budgetary rules). As a consequence, as the critics of the current rules argue, only 14 of the EU’s 27 member states did not violate the debt criterion in 2022 (see chart).

In an attempt to break the deadlock, in April 2023 the European Commission came up with a proposal that provided for the relaxation of the nominal convergence criteria and the establishment of individual debt reduction paths for each country. This was clearly a move in favour of the supporters of greater flexibility, of which Germany did not approve. Berlin believed that the reform in its proposed shape would ultimately destroy the idea of sustainable public finances in the EU. However, the German government’s resistance weakened as the European economies were plunging deeper into stagnation: this ultimately came to include Germany itself, whose GDP shrunk last year. Germany’s arguments for maintaining restrictions were also defeated by demands to increase strategic spending on climate protection, new technologies and defence. The decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of November 2023 turned out to be a painful blow to Berlin, as it accused the government of bypassing its own ‘debt brake’ (see Germany: Constitutional Court deprives the government of €60 billion earmarked for transformation). All this made it more difficult for Germany to act as the defender of the ‘culture of stability’ within the EU, and the advocates of change did not miss the chance to capitalise on this.

The deadlock, which had been ongoing for many months, was finally overcome at the end of 2023 thanks to direct negotiations between the finance ministers of Germany and France, Christian Lindner and Bruno Le Maire (Italy’s significant participation has also been mentioned). Their joint proposal was submitted at the emergency meeting of the EU Council on 21 December, and was supported by all the other member states.

Chart. General government debt in EU countries in 2022 (% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat.

Reforms to the SGP

The most important change is the introduction of individual debt reduction plans. Governments will have more time to put their public finances in order, but this will require negotiating four-year plans with the European Commission. The details of each plan will depend on many factors: expected GDP growth, market capital prices, demographic conditions, the state of the labour market, etc.

These plans may be extended by three years if a given country carries out major reforms during this time and allocates significant funds to improve infrastructure, education and competitiveness (investments, broadly understood). This criterion will also include expenditure on strategic public goods such as national defence. The agreement also states that the budget deficit in 2025–7 will not include the costs of servicing the debt incurred under the pandemic recovery fund, which will offer heavier-indebted countries a little more space to increase pending.

The reform also includes some proposals which conform to the German demands for maintaining fiscal discipline. One of its key principles is that countries whose debt exceeds 60% of GDP must reduce it by at least 0.5 percentage points every year. If the debt is higher than 90%, the annual reduction should be at least 1 percentage point. This changes the previous rule requiring the part of debt above 60% of GDP to be reduced by 1/20 per year, which was more restrictive but in practice was not realistic. If the old rules still applied, the countries with 100% or higher debt (Greece, Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, Belgium) would have been forced to make drastic cuts.

Another way to strengthen discipline is the guideline that in the long term EU member states should maintain a ‘safe distance’ from the permitted 3% limit. It should now be 1.5 percentage points, which shows that the rules have clearly been tightened.

The final element of the reform is more effective enforcement of SGP regulations. Under the new regime, the Commission will be able to launch an excessive deficit procedure not only when its value exceeds 3%, but also when a member state fails to respect the agreed path for debt reduction. A government in breach of these rules will face a fine of up to 0.05% of GDP, calculated every six months until the breach ends.

Something for everyone

The proposed reform offers the opportunity for all participants to announce success in the political dispute over the shape of the fiscal rules. The idea of ‘making the SGP more realistic’, which is necessary in times of the polycrises and strategic challenges facing Europe, has led to the creation of a formula that meets all of the surprisingly numerous expectations.

France and the ‘southern’ countries have the most reasons to be satisfied, as individual debt reduction paths and investment exceptions are to be introduced. This is also a victory for the Commission, which is additionally pleased to have greater influence on the economic policies of EU countries by negotiating multi-annual economic plans and more easily accessible sanctions. Even Germany can say that the outcome of the negotiations is satisfactory: it managed to defend its nominal criteria, and even fortify them with additional safeguards and a restriction mechanism.

The proposed changes favour those countries which are planning to increase public spending in strategic areas, such as the members of NATO’s eastern flank which have been forced to expand their defence budgets in the face of the war in Ukraine. This applies especially to Poland, which intends to allocate 3.1% of GDP on defence in 2024. The new regulations take into account the opportunity to conclude agreements on debt reduction paths, which also gives the Polish government more freedom in planning other investment expenditures and the option of avoiding the excessive deficit procedure. It is also worth emphasising that, since Poland is outside the eurozone, it will probably be subject to a slightly less restrictive sanctions regime.

Expert opinions are more nuanced. Incentives to undertake reforms that may result in reductions of budget deficits in the long run (such as the liberalisation of the labour market and increases in the retirement age) merit a positive assessment. Moving away from a short-term fiscal perspective towards building financial stability in the longer term and finding a better balance between incentives and restrictions are also considered steps in the right direction. However, there have been some critical voices as well. The complexity of the detailed rules and exceptions, which leave a lot of room for interpretation (including political interpretation), is still a weakness of the SGP. This is also true of the planned agreements on ‘debt reduction paths’ to be agreed between Brussels and individual governments. Concerns that the primacy of sustainable finance will be washed out of the EU system by vague investment definitions and weak sanctions are difficult to deny.

All this will certainly be discussed in the course of the negotiations, which will begin after the Commission has prepared the required legislation. The discussions between the European Parliament and the EU Council will be crucial. If they proceed without disruptions or major controversies, the new regulation will come into force before the European Parliament elections in June 2024.