Gazprom in 2023: exports to Europe stabilise, China’s importance grows

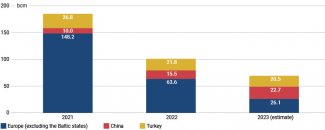

According to estimates published by the Argus agency, in 2023 Gazprom sold 69.3 bcm of natural gas to the so-called ‘far abroad’ countries (Europe excluding the Baltic States, plus Turkey and China). This represents a decrease of nearly 33% compared to 2022, when the company exported almost 101 bcm of gas to these countries. 2023 was the second year in a row when the Russian monopoly reported falling sales in this direction: in 2021, it shipped 185 bcm of gas to the ‘far abroad’.

Pipeline exports fell in the two main directions: towards Europe and Turkey. 26.1 bcm of gas flowed to Europe, about 59% less than in 2022. According to the quoted data, Turkey received 20.5 bcm of pipeline gas, compared to 22 bcm in 2022. In contrast, Gazprom reported an increase in its sales to China: it shipped 22.7 bcm of gas there via the Power of Siberia-1 pipeline, a 47% increase from 2022. As a result, China became the largest single importer of Russian pipeline gas; in the western direction, this fuel is shipped to different European countries, including Hungary and Austria.

Chart. Gazprom’s exports to the so-called ‘far abroad’ countries in 2021–2023

Source: author’s own compilation based on data from Gazprom and Argus.

Last December, Gazprom’s Board of Directors approved funding for the company’s 2024 investment programme totalling 1.574 trillion roubles ($17.8 billion), over 20% less than a year earlier. These funds will be used to finance projects which are priorities for the company’s further development, such as expanding extraction fields, building new gas pipelines and increasing the capacity of the existing ones, and also domestic gasification.

Commentary

- Taking into account the volumes of Gazprom’s supplies to Europe that have been reported in recent weeks, Europe’s imports of Russian gas may rise this year compared to 2023. After last year’s record-low Q1, Gazprom’s supplies to Europe gradually increased. In Q4, their volume stood at 8.3 bcm, 50% more than in January-March and the highest figure since the Nord Stream gas pipelines exploded in September 2022, which rendered this route unusable. The current level of shipments indicates that Russian gas exports to the West have stabilised after Russia started deliberately reducing its shipments back in 2021 as part of its policy of using gas supplies to further its political aims. It is possible that, at this stage, the Kremlin has allowed Gazprom to increase its shipments in the hope of strengthening its own position in order to subsequently take advantage of it to extract concessions in the context of continued gas transit through Ukraine.

- Russian gas sales to the European market could increase in 2024, but maintaining this trend may prove difficult next year. The current transit agreement between Gazprom and Ukraine’s Naftogaz expires at the end of 2024. At present, around half of Russian pipeline gas exports to Europe are shipped via Ukraine’s transmission system: in the second half of last year, it accounted for 48% of Russian gas shipments to Europe while the remaining 52% went through TurkStream, but the former route saw faster growth. Ukraine has been signalling its reluctance to extend this contract for political reasons. Without the route through Ukraine’s territory, the only available path for direct gas transfers to the West will be the Bulgarian section of TurkStream, which has a relatively small capacity of 15.75 bcm/y.

- Further supplies through Ukraine depend on a political decision: Gazprom has expressed its willingness to fulfil the existing contracts, but the attitude of the EU remains uncertain, as it has set the goal of phasing out Russian gas by 2027. Discontinuing or limiting the use of the route via Ukraine as early as in 2025 would bring the EU closer to achieving this goal and also lead to a reduction in Gazprom’s overall exports as it is impossible to build new gas pipelines in such a short period of time. However, pressure from certain companies in some EU member states may push this prospect back – should Ukraine implement the EU’s network regulations, those who remain interested in receiving Russian gas could reserve capacity in the Ukrainian system through auctions. A transit agreement between the two countries would then be redundant.

- Offsetting the volumes Russia has ‘lost’ in Europe with increased exports to other markets is still a distant prospect. Contrary to the statements coming from Moscow, China’s rise to become the most important customer for Russian gas does not bring the Kremlin significantly closer to realising its plans to redirect sales from Europe to China. In fact, this rise is the result of a scheduled increase in the capacity of the existing Power of Siberia-1 pipeline, which is expected to reach its maximum capacity of 38 bcm/y in 2025. Combined with the so-called Far Eastern Route, which is currently under construction, pipeline exports to China could reach a maximum of almost 50 bcm/y by 2027, but this will still fall far short of the volumes that were shipped to the West before 2022 (up to around 180 bcm/y). Moreover, despite Russian efforts throughout last year, no progress has been made in talks on the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline with a planned capacity of 50 bcm/y that could allow Russia to divert its gas to China from the resource base which supplies Europe (see ‘The Power of Siberia-2 gas pipeline remains in the design stage’). According to recent media reports, the project has faced delays as a result of disagreements between Russia and China over its terms of use, including the pricing formula.

- Turkey is another export direction with growth potential. In this context, Russian decision-makers have been making a lot of Turkey’s idea of building a gas hub as an alternative option to the defunct Nord Stream pipelines. According to the Kremlin, gas supplied by Russia would be re-exported from Turkey to other markets, including European ones. However, this concept has not been given any concrete form yet. There are also clear differences between the interests of both sides as Turkey seeks to re-export gas from many directions. Moreover, the sheer ambition of Russia’s stated goal, which is to replace the Nord Stream pipelines, suggests that it will be necessary to significantly increase the capacity of the existing connections between the two countries or to build new sections. This, in turn, even if it proves feasible, will extend the timeframe for implementing Russia’s plans to re-export its gas. The current routes for transporting gas to Turkey, one branch of TurkStream and BlueStream, have a maximum capacity of around 31 bcm/y. For comparison, Nord Stream’s four branches had a total nominal capacity of 110 bcm/y.

- Gazprom’s signals that it will reduce its investment expenditure are a direct result of its export problems illustrated by falling supplies to the ‘far abroad’. Dwindling foreign sales and lower global hydrocarbon prices in 2023 have forced it to scale back its investment policy. The vague prospects for a tangible improvement in Gazprom’s financial position in the short to medium term suggest that the company will find it difficult to create the new gas pipeline connections that it needs to rebuild its position on the international market. Furthermore, its situation may be exacerbated by the fact that the Russian government appears to be banking on LNG exports (see ‘Russia: liberalisation of LNG exports’). If the pressure to develop this sector continues, the state may well shift its involvement and resources to LNG production at the expense of gas pipeline projects.