Dispute over the justice system in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Since January 2024 the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has been functioning without any judges from Republika Srpska (RS; for the specific features of the political system in BiH, see Appendix). This is because the RS government has been blocking all efforts to fill these vacancies and demanding the removal of foreign judges from the Court, which is composed of nine judges, including four elected by the Parliament of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, two elected by the Parliament of Republika Srpska, and three foreigners appointed by the European Court of Human Rights.

At the root of the dispute are the rulings by the Constitutional Court which Republika Srpska’s political elite views as unfavourable. In June 2023, RS deputies adopted laws under which the Court’s verdicts will not apply on the territory of this entity, while decisions by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina will not be published. The High Representative Christian Schmidt has waded into the dispute over the country’s judicial system by repealing the regulations passed by Serbian deputies and amending Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Criminal Code. In light of these amendments, failure to implement the High Representative’s decisions is punishable by up to five years’ imprisonment.

Commentary

- The dispute over the Constitutional Court is a sign of the deepening institutional crisis in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik has repeatedly challenged the state institutions, called for the office of High Representative to be terminated; he has also demanded that the international judges be removed from BiH, while threatening that Republika Srpska would secede. The Court has issued a number of rulings contrary to Dodik’s interests, for example on the seizure of property and on the celebration of Republika Srpska’s state holiday (see ‘Bośnia i Hercegowina – gry separatyzmem Republiki Serbskiej’). As a result of pressure from the government in Banja Luka, no one from Republika Srpska has sat on the Bosnian Court since January 2024: one of the judges ceased to hold office due to old age and another was forced into early retirement, while Republika Srpska’s parliament has deliberately failed to appoint anyone to replace them. This situation has benefited the Bosnian Serb leader, who has used it to give credence to his narrative that the central institutions are ‘anti-Serb’, and that their decisions are taken by the Bosniaks in coalition with the judges appointed by the European Court of Human Rights. The leader of the largest party of Bosnian Croats, Dragan Čović (HDZ BiH), has also called for the foreign judges to be removed from the Constitutional Court, as he seeks greater influence over the appointments of Croatian judges by applying the principle of national parity.

- The central prosecutor’s office has opened proceedings against Dodik for his failure to implement the High Representative’s decisions. The Bosnian Serb leader has been using this fact to rally his electorate and justify the thesis that BiH is a dysfunctional state. Several protests have been held in his defence both across Republika Srpska and in front of the court in Sarajevo, accompanied by a wide-ranging propaganda campaign which has featured billboards with slogans calling for competences at the central level (BiH) to be transferred back to the entity level (RS). The ongoing proceedings have deepened political polarisation, undermined the authority of the Bosnian judiciary and hindered the work of the High Representative in BiH.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina was granted EU candidate status in December 2022, but it needs to fully implement the European Commission’s so-called fourteen conditions before accession negotiations can begin. One of these is the reform of the judiciary. According to a report the Commission published in November 2023, the state of the judiciary in BiH has deteriorated while the central government’s efforts to reform the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council have de facto failed. Thus, the prospects for accession negotiations with the EU to be opened this March are uncertain.

Appendix. The specific features of the political system in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is a multi-ethnic state whose current political system was defined in the 1995 Dayton Agreement, which ended three and a half years of bloody civil war. BiH’s constitution, which is one of the annexes to this agreement, provides for a specific system of government based on the principles of territorial autonomy, ethnic parity and veto powers that can be used to defend the interests of the country’s individual nations.

The political system

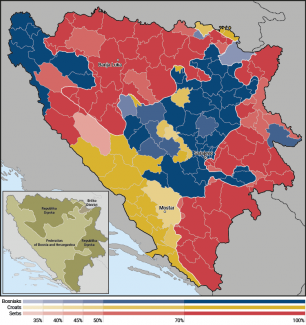

Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two parts, the so-called entities: The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), which is divided into 10 cantons, and the unitary and strongly centralised Republika Srpska (RS). The Brčko District is a separate, autonomous territorial unit due to its strategic location: it divides RS in half and borders Croatia.

There are three tiers of government in BiH: the centre (BiH), the entities (FBiH and RS) and the cantons (only in FBiH). At the central level, the highest office is the Presidency of BiH: this is the collective head of state, which consists of three representatives, one each for the Bosniaks, the Serbs and the Croats, who are elected for four-year terms in direct elections. At the central level, legislative power is vested in a bicameral parliament while executive power is exercised by the Council of Ministers, which has limited competences, mainly in foreign and security policy, fiscal and budgetary policy and the judiciary; it consists of nine ministries. Most of the powers relevant to the daily lives of people, that is those covering the areas of education, health care and infrastructure, are exercised at the entity level (RS and FBiH) or the cantonal level (in FBiH). Each of the two entities, FBiH and RS, also has its own president and a bicameral parliament; in the decentralised FBiH, assemblies and cantonal governments also exercise certain powers.

One of the pillars of the operation of consensual democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the so-called principle of protecting vital national interests. In theory, it was supposed to ensure the equality of all the three constituent peoples in the country, the Bosniaks, the Serbs and the Croats; but in practice it has been used to block political initiatives undertaken by any given group’s opponents.

The role of the international community

One of the distinct features of political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the office of the High Representative (OHR), who has broad legislative and executive powers. His task is to implement the civilian provisions of the Dayton Agreement, while the ‘Bonn powers’ that were established in 1997 give him almost unlimited legislative and executive competences, including the power to dismiss officials in the country, enact legislation and enforce its implementation. In addition, the Constitutional Court includes three foreign judges who are appointed by the European Court of Human Rights. The European Union’s EUFOR Althea military operation also operates on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the goal of ensuring internal security in the country.

The main areas of dispute

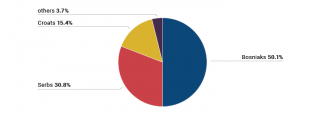

- The shape of Bosnia and Herzegovina: the Bosniaks (c. 50% of BiH’s population) support the idea of a centralised state (in the maximalist version, they call for the abolition of the territorial autonomy of RS and the cantons); the Bosnian Serbs (c. 31%) seek maximum self-governance for RS and have recently invoked the idea of the ‘original Dayton’, which guaranteed a high degree of independence for both entities, as they strive to maintain the broadest possible competences within RS: this has led to their boycotts of the central institutions and disputes over real estate; the Croats (c. 15%), for their part, demand the broadest possible representation at all levels of government, and in extreme cases, even the establishment of a third, Croatian entity.

- The role of the international community: the Bosnian Serbs call for an end to international oversight, including the removal of foreign judges from the Constitutional Court and the abolition of the OHR.

- Politics of memory: each of the three nations living in BiH nurtures its own attitude towards the events during the war of the 1990s, and often also towards World War II.

Chart. The ethnic structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Source: the 2013 census.

Map. Bosnia and Herzegovina: the dominant ethnic groups in individual municipalities

Source: the 2013 census.