An increase in Russia’s agri-food exports

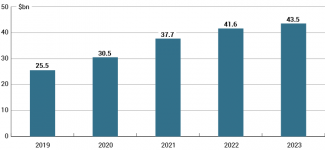

Despite the war and the sanctions, over the last two years the size of Russia’s agri-food exports has continuously risen, although the pace of this increase has now slowed down. In 2023, the value of supplies delivered to foreign markets stood at around $43.5 bn, which accounted for around 10% of the Russian Federation’s (RF) total export revenues. Alongside this, the importance of the European Union’s market has gradually decreased. At present, the EU member states receive around 6% of Russian agri-food exports, which accounts for 2% of the EU’s total imports in this category of goods. Poland imported agri-food products from Russia worth a mere €350 mn, or around 1% of its total imports in this category.

In the coming years, due to obstacles to cooperation with Western partners, modifications to the logistical operations resulting from the war and the restrictions imposed, it is expected that the pace of growth of Russia’s agricultural production will decline, and that will translate into a drop in export revenues.

Sanctions have bypassed the Russian agri-food market

In line with the G7’s decisions, agri-food products and mineral fertilisers have been exempted from the sanctions imposed on Russia by the West. This is due to the need to ensure global food security, especially as global agri-food prices saw a dynamic increase since the end of 2021 and in the first months of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which added to the destabilisation of the situation in the Global South. The RF’s agricultural sector has been indirectly hit by the Western companies’ decision to boycott the Russian market and to sever their cooperation with Russia in areas such as logistics, insurance and trade.

Development of production and exports

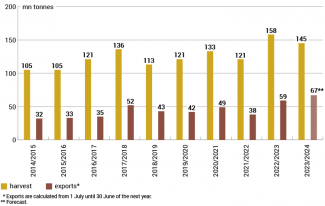

Russian agriculture has recorded dynamic growth for more than a decade. This concerns the cereals sector in particular, and has translated into increased production and exports (see Charts 1 and 2). In 2023, Russia’s harvest of various types of cereals amounted to 145 mn tonnes (including 100 mn tonnes of wheat), around 10% less than the bumper year of 2022. Russia’s important position on the global agri-food market is mainly due to its wheat exports (51 mn tonnes, around 20% of global trade) and sunflower oil exports (around 4 mn tonnes, around 30%), although its total share in international agri-food trade is just around 2%.

Cereals and oil crops together accounted for more than 50% of the value of Russia’s total agri-food exports, while fish and seafood accounted for another 25%. However, whereas prior to the invasion revenues from agri-food exports increased by around 20% annually, the pace of this growth slowed down following the invasion of Ukraine, and stood at 5% (y/y) in 2023.

It should be noted in this context that Russia has ceased to publish detailed statistics on its foreign trade since its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The Federal Customs Service and the ministry of agriculture only publish incomplete data regarding the performance of the Russian agricultural sector.

Chart 1. The value of Russia’s agri-food exports

Source: Federal Customs Service of the RF.

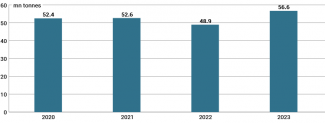

Chart 2. Russia’s cereal harvest and exports

Source: Ministry of Agriculture of the RF.

Despite its policy of import substitution, which has been in place since 2014 and aims to ensure food self-sufficiency for the Russian state, Russia continues to be a major importer of foreign agri-food products. In 2023, its imports in this category were worth around $35 bn, of which around $7 bn were accounted for by goods imported from the EU. Although over time Russia has reduced its purchases of finished products, it continues to rely on imports of agricultural equipment, vaccines, vitamins, animal feed, seedlings, fish fry etc., that is, goods and raw materials which are necessary for sustaining domestic agri-food production.

Re-direction of exports to ‘friendly’ states

Russia now exports the majority of its agricultural produce to non-Western states. In this context, the Kremlin has consistently attempted to increase Russian exports to new markets. In 2023, Russian agri-food exports to ‘friendly’ states, meaning those which did not join the sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine, rose by 20%. As a consequence, the total share of these states in Russia’s agri-food exports rose to around 90%. In 2023, the biggest importers of Russian agri-food products included China, Turkey, Egypt, Kazakhstan, Belarus, South Korea, India and Saudi Arabia.

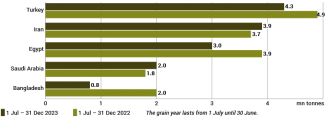

The biggest importers of cereals, which are Russia’s main export commodity, included Turkey, as well as African and Middle Eastern states. Interestingly, although China, which is the principal global importer of cereals, has begun to increase its trade with Russia, it continues to impose limits on agri-food imports from this country (on wheat in particular). In 2023, China imported a mere several hundred thousand tonnes of wheat from Russia (see ‘Russia seeks access to China’s agricultural market’).

Chart 3. Main importers of cereals from Russia

Source: the Russian Union of Grain Exporters.

Russia’s exports to the EU: greater volume, smaller revenues

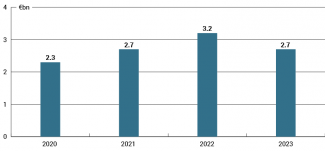

The role of the European Union in Russia’s agri-food exports has been on the wane. In 2023, the EU member states accounted for a mere around 6% of these exports, while prior to the invasion of Ukraine the figure was more than 12%. In 2022 and 2023, the EU imported agri-food products from Russia worth €3.2 bn and €2.7 bn respectively (see Chart 4), or less than 2% of its total imports in this category of goods.

Prices have had a major impact on the EU’s agri-food imports from Russia. In 2022, the global price hike translated into an increase in the value of these imports, even though their volume decreased. In 2023, as prices dropped and the volume increased, the value of EU’s imports from Russia fell (see Charts 4 and 5). It should be noted that an increase in the physical volume of imports was only recorded for several types of commodities. The biggest increase involved those categories of goods which are referred to using the following tariff codes:

- HS 07: vegetables and other products (including pulses), an increase of 6 mn tonnes to 9.7 mn tonnes,

- HS 10: cereals, up 5.5 mn tonnes to 15.3 mn tonnes,

- HS 03: fish and other products, up 2 mn tonnes (in 2022 their imports were insignificant),

- HS 12: seeds, oil crops and other products, up 2 mn tonnes to 5 mn tonnes.

The increase in imports of these products from Russia was most likely due to their attractive price. According to Russian estimates, in the second half of 2023 the price of a tonne of Russian cereals and pulses was around $14 lower than the price of their European counterparts.

In 2023, the main agri-food products the EU imported from Russia (in terms of value) included:

- fish (HS 03) – around 30% of the value of the EU’s agri-food imports from Russia,

- cereals (HS 10) – around 20% (including wheat – 10%, corn – 4%),

- oilseed cake (HS 23) – 15%,

- leguminous vegetables (HS 07) – 10%,

- linseed (HS 12) – 7.5%.

Chart 4. The value of the EU’s agri-food imports from Russia

Source: Eurostat.

Chart 5. The volume of the EU’s agri-food imports from Russia

Source: Eurostat.

Russia’s biggest export partners in the EU

In 2023, the main recipients of Russia’s agri-food exports in the EU included Latvia, the Netherlands, Spain and Germany. The value of the exports to each of these countries exceeded €300 mn, while an annual increase in this value was only recorded for Spain. This country has mainly boosted its imports of pulses from Russia (5 mn tonnes).

It transpires from an analysis of the statistics that as regards Latvia, the biggest increase in the volume of agri-food products imported from Russia compared with 2022 involved two types of goods, cereals and oilseed cake. As for the Netherlands, the vast majority of its imports from Russia involved fish. It has not increased its imports significantly y/y. Meanwhile Germany has reduced its imports of the main categories of Russian agri-food products, namely fish and oilseed cake.

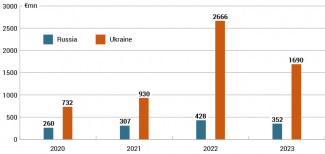

Poland has reduced its imports from Russia

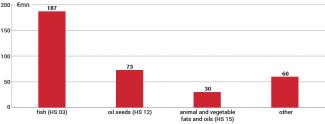

According to Statistics Poland, in 2023 Poland imported agri-food products worth more than €350 mn from Russia (compared to almost €430 mn in the previous year). For comparison, in these two years its imports of this category of goods from Ukraine stood at €1.69 bn and €2.67 bn respectively (see Chart 6). The total value of agri-food products imported by Polish companies in 2023 stood at €34 bn. The main types of agri-food products imported from Russia included fish, oil crops, as well as animal and vegetable fats and oils (see Chart 7), and cooking oil, oilseed cake, corn and wheat from Ukraine.

Since the data compiled by Statistics Poland as regards the volume of imported goods is incomplete (especially for 2022), it is difficult to find out which imports from Russia recorded an increase in 2023. No comparative base is available, especially as regards the three most important categories of goods already mentioned. The import of cereals, which are of little importance in these statistics, has doubled and reached 12,000 tonnes (for comparison the total imports in this category stood at 3.3 mn tonnes).

Chart 6. Poland’s agri-food imports from Russia and Ukraine

Source: Statistics Poland.

Chart 7. The commodity structure of Poland’s agri-food imports from Russia in 2023

Source: Statistics Poland.

The agricultural market in the Kremlin’s domestic and foreign policy

In domestic policy, the Kremlin is mainly using the agri-food sector to stabilise the social situation. By controlling this sector and regulating the market, it is attempting to ensure that Russian citizens retain access to basic foodstuffs at affordable prices. In addition, the rising export revenues are an important source of income for the Putinist elite. As a consequence, members of this elite have increased their involvement in the agri-food sector, which in turn has resulted in its consolidation around big companies linked with the Kremlin. In 2022, more than 70% of the grain Russia sold to foreign markets was controlled by the ten biggest exporters. At least two main grain traders are linked with the minister of agriculture Dmitry Patrushev (the son of Nikolai Patrushev, the Secretary of the Security Council of Russia), while another two are managed by the VTB bank, which is owned by Vladimir Putin’s aide Andrei Kostin. Aleksandr Vinokurov, foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s son-in-law, holds a stake in one of these companies. Until June 2023, around 15% of Russia’s grain exports was supervised by three international traders, Cargill, Viterra and Louis Dreyfus, which later withdrew from Russia.

The Kremlin has also consistently used the foodstuffs market as an instrument to step up pressure on the West, mainly to mitigate the sanctions imposed on Russia. Alongside this, it has used the agricultural sector as an important tool in its foreign policy towards the states of the Global South, as it is intensively seeking their support (including in the forum of the United Nations). In the first year of its full-scale war with Ukraine, it deliberately fuelled the global food crisis and thus contributed to a rise in the prices of cereals and mineral fertilisers. In an attempt to destabilise the global agri-food market, Russia blocked the main routes of Ukraine’s agri-food exports and damaged its farming infrastructure and harvest (see ‘Russia is weaponising food’). In addition, it introduced regulations to limit its own exports. From the beginning of the war, it also sabotaged the safe corridor for transporting Ukrainian agri-food products & mineral fertilisers from the Black Sea ports, which was launched in July 2022 in response to requests from the states of the Global South (in particular Turkey), and imposed limits on the volume of the goods exported. It withdrew from this initiative in July 2023. These actions mainly affected the poorest countries, particularly in Africa. However, the Kremlin consistently blamed the West for the price hikes and, in an attempt to demonstrate its alleged concern for the southern states, in 2023 it provided some of them (for example Somalia, Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe and Mali) with small volumes of grain (a total of 200,000 tonnes) free of charge.

Forecasts of a decline in export revenues

The negative consequences of the Western sanctions and the growing costs of the ongoing war are having an increasing impact on the Russian agricultural sector. Although the Kremlin’s attempts to make this sector become independent of Western imports following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 did result in an increase in domestic agri-food production, they have failed to push the sector into fully replacing foreign goods with domestically-produced ones. This particularly concerns those goods whose production requires significant financial outlays and advanced technology, such as agricultural machines, seedlings, vaccines etc. Following the launch of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the cost of their deliveries has increased significantly not only due to the devaluation of the rouble, but also due to modifications in logistical operations and difficulties with effecting international financial transactions. As a consequence, for example, in recent months Russia has seen a shortage of eggs and a hike in their price. Grain producers have also faced serious problems. However, these mainly result from the Kremlin’s policy which is causing a decline in production profitability. The government-imposed tariffs and export quotas have reduced the attractiveness of exports, which thus strips the business owners of a significant portion of their income. In addition, their profits are affected by internal market regulations which discourage them from making further investments in production. As a consequence, Russian farmers are facing the problem of overfilled storage facilities, as at the beginning of 2024 Russia’s domestic stockpile of wheat alone reached an unprecedented volume of 36 mn tonnes, up 15 mn tonnes compared with 2023.

The Russian ministry of agriculture has taken note of the mounting problems. In its amendments to their strategy for the sector’s development until 2030, it slashed its forecasts of an increase in agricultural production from 3% to 1.5% annually. By the end of the present decade, then, Russia’s revenues from agri-food exports are expected to shrink by 25% compared with the 2023 figures, to $36 bn. This drop will have a negative impact on the state’s policy of support for the agricultural sector because the subsidies and grants offered to farmers are partly funded from the tariffs imposed (for example) on grain exports.