Germany: a chance to overcome the economic crisis

The continuing stagnation in Germany raises concerns about a permanent weakening of the economy’s competitiveness and erosion of the prosperity that has been achieved over the past few decades. However, it is not a foregone conclusion that these pessimistic scenarios will materialise. The factors that have led to the current crisis, such as the surge in energy prices, the global economic downturn and rising inflation, are receding, so a gradual return to an upward trend is possible. German industry may also help in the process of the country’s economic recovery, as it still has significant resources to trigger innovation development. However, hopes for a sustainable and faster economic recovery may be thwarted by politicians struggling to formulate a recipe for stimulating growth and implementing the necessary structural reforms.

The situation in Germany is concerning. By the end of 2022, the growth engine stalled, and in subsequent quarters, a minor but persistent recession set in (-0.3% GDP). A recovery was expected in 2024, but the latest forecasts are far from optimistic: instead of the previously assumed 1–1.5% growth, most analytical centres now predict at best a 0.2–0.5% stagnation (see table).

Complex structural problems are also standing in the way of a return to growth. Germany is grappling with increasing problems caused by demographics, an excessive dependence on the global economy, expensive energy and the need to adapt to new technologies. The situation has been further worsened due to errors in economic policy, such as insufficient public investment, excessive bureaucracy and higher corporate taxes than other countries. The German economy is also facing greater pressure from competitors than in previous years. China has begun flooding the global markets with more advanced products, such as electric cars (see ‘Fear of retaliation: Germany's concerns about punitive tariffs on electric cars from China’), and the US has been attracting companies with cheap electricity and generous subsidies.

These data and conditions cannot be ignored, but talk of a decline in Germany’s economic power is definitely exaggerated. The county is not experiencing a crash with a significant drop in GDP, nor is it faced with a risk of skyrocketing unemployment or the collapse of public finances. Amid the flood of pessimistic forecasts regarding Germany’s economic condition, two important issues often escape attention: the diminishing impact of the external circumstances that exacerbated the crisis, and the fact that the German economy still has genuine advantages.

Table. GDP and inflation in Germany and the European Union in 2023–2025 (in %)

Source: European Commission.

The temporary factors

A significant part of the downturn can still be attributed to the pandemic, which disrupted international supply chains and suppressed demand in the global economy. This was a painful blow for Germany’s export-oriented companies, and its effects are still being felt, even though some time has already passed since the pandemic. Another blow came with the war in Ukraine; above all, it led to an increase in energy prices, followed by a level of inflation unseen in decades. The revival after the pandemic crisis quickly fizzled out.

However, there are indications that Germany’s external environment will improve in 2024. Many forecasts predict a gradual recovery inside the EU (with GDP growth of 0.9% in 2024 and 1.7% in 2025), which is still the main destination for German exports. The global economy is also stabilising; analysts at the International Monetary Fund believe it will grow at a rate of over 3% annually, and traditional trade orientation may still help Germany.

The next good news concerns the energy market. According to data from the Federal Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW), the average electricity price for small and medium-sized enterprises (consuming between 160,000 and 20 million kWh of energy) in new contracts dropped from 24.46 eurocents/kWh in mid-2023 to 17.65 eurocents/kWh in early 2024 – a decrease of nearly 30%. In 2022, it topped 43.20 eurocents/kWh. Customers are likely to continue to pay more for electricity than before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, but it ceases to be a risk factor in companies’ investment plans. According to a report from the German Economic Institute in Cologne, energy prices should no longer affect the competitiveness of the most ‘sensitive’ consumers by no later than 2030. However, this requires continued investment in energy and market interventions.

This is also true for inflation. In 2022, it was close to 9% (average index), and in February this year, it dropped to 2.5% (Destatis data) – this being the lowest rate since mid-2021, only slightly higher than the European Central Bank’s monetary policy target. Similar trends can be observed in most eurozone countries, so interest rates may soon fall, and loans for businesses and individuals may become more accessible. A decrease in inflation will promote real wage growth, encouraging consumers to increase spending.

The structural advantages

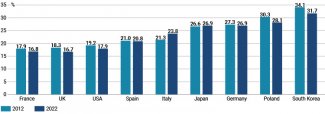

Industry is a major contributor to Germany’s GDP. According to the World Bank, it makes up 27% of GDP, which is much higher than in most developed EU economies (see chart). The pandemic and the energy shock were an exceptionally difficult period for this sector. However, challenges had already begun to accumulate several years earlier. Around 2018, manufacturing companies were already feeling the effects of growing competition from other countries (mainly China), as well as the costs of the energy transformation, digital backwardness, the development of electromobility and problems with workforce availability. Industry was thus hit by stagnation.

The current situation in industry can be interpreted in two ways. The first speaks of a deep existential crisis questioning Germany’s previous competitive advantages and the traditional role of this sector. The second sees the current weakness as a structural change that, given industry’s exceptionally large share in German GDP, would have been inevitable anyway. This may lead to the disappearance of some industries but also, in the optimistic scenario, the emergence of new products, entities and areas of expansion. Since Germany has several significant advantages, the latter scenario is more likely.

Its first advantage is a solid innovation base. In 2021, Germany had the highest share of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) graduates among university graduates worldwide and is still able to file close to 60,000 patents (in 2022), placing it among the top global economies, just behind the USA. This is largely due to significant spending on research and development, exceeding 3% of GDP. According to the ‘innovation capability’ (Innovationsindikator 2023) study conducted by employers’ organisations and leading research institutes, Germany ranked 10th among 35 developed economies, far ahead of France (18th) and Italy (25th), and even the United States (14th). It was found that over the past two decades, Germany had maintained a fairly high and stable position among the world’s most innovative economies.

In addition, German companies are beginning to make up for the time they lost in the previous decade. A lot is happening in the German automotive industry, which is introducing new electric engines and battery models into production. In areas where the gap with competitors has become too large (one example being digital technologies), they are forming partnerships with foreign corporations, especially with American big tech companies. It cannot be ruled out that it will be Mercedes and BMW – not Tesla – that will lead the way in the development of autonomous vehicles and the implementation of artificial intelligence in control systems.

The Mittelstand sector of medium-sized firms, typical of German capitalism, still has a lot to offer. This sector has experienced problems in recent years, not only due to the downturn, increasing competition and labour shortages, but also because of difficulties with succession planning for retiring owners. However, it is worth keeping in mind that these companies typically have low debts and are quite flexible, which makes it easier for them to change course in rapidly changing markets. Many of them continue to dominate in small product niches in the global economy, which still gives them an edge over their rivals.

Chart. Industry’s share in the GDP of selected countries in 2012 and 2022 (by added value)

Source: World Bank.

The weak point: politics

Germany could probably have returned to the path of growth sooner, if it were not for the political challenges. The federal government has a difficult task because it is now dealing with a complex structural crisis – essentially a multi-crisis. Unlike under Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s administration, which overhauled the labour market two decades ago (the Peter Hartz reforms as part of the Agenda 2010 programme), today it must find solutions that simultaneously address issues related to demographics, energy, technological progress, social security and access to capital. Further factors hindering the development of these solutions are: the permanent election campaigns for local parliaments, a lengthy legislative process and a complicated distribution of competencies between the federal states and the centre, inherent in the German political system. Individual breakthroughs, such as quickly shifting gas supplies from Russian imports to LNG, are rather exceptions that prove the rule.

The fiscal regime is another source of difficulties. The constitutional ‘debt brake’ introduced after the financial crisis (2007–9) severely restricts the government’s freedom to take on new debt, and thus to increase investment expenditures. Attempts by Olaf Scholz’s cabinet to circumvent this regulation ended in a crushing judgment by the Federal Constitutional Court in November 2023, forcing the coalition into painful budget cuts (see ‘Germany: the budget crisis has been resolved’), which certainly does not make stimulating growth any easier.

The situation within the government coalition is also a challenge for the economy. Disputes between the FDP (advocating tax cuts) and the SPD and Greens (who want to increase spending and state intervention) generate a lot of uncertainty in the economy. A struggle has been underway inside the coalition for many months regarding the ‘Growth Opportunities Act’ (Wachstumschancengesetz), which was supposed to contain favourable tax solutions. This has not helped businesses make investment decisions. The problem is that easy compromises just ahead of the election campaign are unlikely. Therefore, if Germany manages to return to the path of growth, it will not be because of the politicians but rather in spite of their actions.