Presidential election in Slovakia: a full house for the left-nationalists?

The first round of the presidential election scheduled for 23 March will primarily be a clash between the candidate of the predominant section of the government camp, the Parliamentary Speaker Peter Pellegrini, and the former minister of foreign affairs Ivan Korčok, who represents the liberals and the centre-right. Polls from the major agencies unequivocally indicate that these two candidates will face each other in the runoff two weeks later. Pellegrini, who tops the polls for public trust in political leaders, promises ‘peace’ to Slovaks, assuring them of harmonious cooperation between the head of state and the government. On the other hand, Korčok, who has been endorsed by the incumbent president Zuzana Čaputová, whose term will end in June, argues that he is the last hope for blocking, or at least slowing down, the processes of state capture pursued by the ruling left-nationalist camp. Even though the president has modest legislative prerogatives, the two most recent presidents of Slovakia have played significant roles during government crises and served as important points of reference in public debate, while also having an influence on crucial nominations in the state administration.

What is at stake in the election?

The election comes at one of the most pivotal moments in Slovakia’s post-Czechoslovak history. The government Robert Fico formed in autumn 2023 has announced or implemented a series of measures which could result in Slovakia becoming isolated in the international and European community, although the prime minister’s sharp rhetoric in this regard is accompanied by mitigating gestures (see ‘Fico meets Shmyhal: Slovakia's two-track Ukraine policy’). The situation is different in domestic politics, where, in addition to controversial proposals to change the criminal law, actions are being taken to curb the activity of those NGOs that are hostile to the government, and the government is likely to take over the public media soon (see ‘Slovakia: the Fico government has presented its platform and won a vote of confidence’). Leading private media outlets (especially the most popular television station, TV Markíza) have reported that pressure has been put on them and that their owners have been blackmailed, proof of which seems to be seen in their criticism of the government in recent weeks. The Special Prosecutor’s Office is a body that has contributed to revealing the abuses of subsequent cabinets, and its liquidation (on 20 March) was approved. A similar function was performed by the so-called National Criminal Agency (NAKA); its top investigators have been taken off their cases.

If Pellegrini wins the election, the left-national camp, which has been in power since autumn 2023, will effectively hold all the power in the country. The only major institution beyond its reach would be the Constitutional Court, where judges will also be gradually replaced by those appointed by the president from the individuals elected by the parliament.

On the one hand, the head of state has relatively narrow powers in the legislative process – the president has no legislative initiative, and his/her veto can be rejected by any majority coalition. On the other hand, even the recent disputes between Fico and Čaputová over changes in the criminal law have shown that the president does not always lose (see ‘Slovakia: controversial changes to the criminal law, and a dispute with Brussels on the horizon’). As a result of her well-argued motion, the Constitutional Court suspended most of the controversial reforms which would have led to many of the ongoing trials against influential people with close links to the current government being closed. It is reasonably presumed that Pellegrini, who has approved the draft amendments as the leader of the coalition centre-left Hlas party, would not raise any major objections to them as the president. As to those who have already been convicted, he could use the right of pardon (in individual cases) and amnesty (a one-time collective leniency or remission of penalties for crimes or offenses of a given type) as his presidential prerogative. The latter in particular evokes extremely bad associations in Slovakia due to the decision made in 1998 by Vladimír Mečiar, who as the acting president practically guaranteed impunity to those involved in the abuse of power of his government (he was also serving as prime minister at the time). This act was only invalidated in 2017 by the National Council and the annulment was subsequently confirmed by the Constitutional Court.

The campaign and the candidates

Slovakia has seen a relatively calm campaign in which the two frontrunners have been particularly visible in the public space, with Pellegrini predominant. Its intensity was significantly different than what was seen ahead of the parliamentary elections. From the outset, some of the contenders have not attempted to conceal that their participation in the presidential race has been aimed at achieving goals other than the presidency, such as strengthening the position of their parties ahead of the June elections to the European Parliament (EP) or, more broadly, in the current political competition. With minimal spending on billboards and posters (those of the less popular candidates are virtually invisible), they have received much more media coverage than they could have otherwise expected. This applies, for example, to the former prime minister Igor Matovič, who is currently the leader of the anti-corruption and conservative party Slovakia (formerly OĽaNO). He had been marginalised on the opposition scene (he was not invited to anti-government protests), as a result of which his party lost support in the polls. As with another contender, the historian Patrik Dubovský, he will run in the European Parliament elections from the joint list of Slovakia and For the People. In turn, Andrej Danko, the leader of the nationalists who are part of the government coalition declared he himself would take part in the presidential race. This was after unsuccessful negotiations with Pellegrini in which he tried to secure the position of parliamentary speaker or economy minister for his party in exchange for his support. When it became clear that his participation could end in embarrassment, he chose to transfer his votes to the leading candidate of the anti-establishment scene, the pro-Russian ex-chief justice of the Supreme Court and former Minister of Justice Štefan Harabin, who stands a fair chance of achieving a support level similar to that five years ago (around 15%). This time, he is no longer under real threat from Marian Kotleba in this part of the political scene: after a group of leading activists left his grouping and then founded a party of their own named Republika (around 5% support, according to polls), the popularity of both his extremist formation ĽSNS and Kotleba himself dropped dramatically. Danko and Kotleba are number one on their parties’ lists in the European elections.

The support for Pellegrini’s campaign from Prime Minister Fico’s Smer party, which is leading in the polls (with around 23%), may prove decisive for the outcome of the presidential race. After his own unsuccessful participation in the presidential election in 2014 and the defeat of Smer’s candidate (current Vice-President of the European Commission Maroš Šefčovič), five years later Fico chose to bet on his former political protégé, Pellegrini. Before that, Fico had promoted him to the positions of speaker of parliament, deputy prime minister and prime minister. Although Pellegrini later left Smer to found his own party (Hlas) and distanced himself from his former boss for a long time, their political pragmatism has brought them together. It is possible that Fico’s endorsement was an important aspect of what ultimately proved to be successful talks on the new coalition government.

In the campaign, Fico is primarily mobilising the anti-establishment electorate, who are now an important section of Smer’s supporters. This is achieved by emphasising the intention to prevent Slovakia’s involvement in the war on its eastern border at all costs, which has also been suggested by Pellegrini himself in a more subtle way. This rhetoric is accompanied by mass leaflet campaigns that play on the anti-American sentiments widespread among the Slovak public. Korčok is branded in them ‘more American than the Americans’ or a ‘figurehead’, while Pellegrini is presented as ‘not a servant of the US, unlike Korčok’. The disinformation campaign has even included false claims that Korčok is a US citizen. What he really has in common with the United States is the fact that he used to serve as an ambassador in Washington. However, the fact that Korčok was sent there by the government led by Pellegrini, who was then a member of Fico’s party, has somehow escaped the attention of his critics.

Fico and Pellegrini have also taken care to ensure the support from the large (8.5% of the population) Hungarian minority. 40% of its representatives intend to vote for the latter in the first round, only slightly less than for Krisztián Forró, who is of a Hungarian ethnic background (Focus agency survey). Pellegrini has an overwhelming advantage over Korčok in this group in a possible runoff (83%–17%). During the last weeks of the campaign, Pellegrini in his capacity as the parliamentary speaker was also received with honours in Budapest (on 11 March). Apart from his counterpart, he also met PM Viktor Orbán, which was an expression of his support for Pellegrini.

While Pellegrini confirmed he would run for the presidency as late as January, Korčok, who is less recognisable, did it much earlier, on the occasion of the anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising last August. Even though Korčok has put a lot of effort into his campaign and has taken care it receives a good assessment in terms of spending transparency (the campaigns of these two contenders are poles apart in the rankings of the local branch of Transparency International), he has not yet managed to find a topic that would resonate more strongly with the majority of Slovaks. For some time, the controversial changes to the criminal law seemed to offer this potential, but since the Constitutional Court suspended their application, the dispute has paradoxically lost intensity, slowing down the dynamics of Korčok’s campaign. Korčok, who has extensive experience in diplomacy but much less in politics, also made several unpopular statements and then attempted to back-pedal. For example, he announced that he was in favour of abolishing the right of veto in relation to EU foreign policy, and then added that he just wanted to start a discussion on this matter. Over time, he also softened his liberal declarations in highly emotional disputes on moral and ethical issues, and thus gained the support of the conservative Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) before the first round.

Prospects

Opinion polls have so far been clearly favouring Pellegrini and Korčok; in recent weeks, not a single poll from a major agency has been published that would predict a winner of the election in the first round or different contenders in the runoff. However, Korčok’s supporters may be concerned that neither of the polls gives him any hope of winning the election; he loses it by a margin of 4.5–12 percentage points (see Appendix). Therefore, his most important task will be to convince a larger share of the two groups that may still constitute a source of additional electorate: conservative residents of the northern part of the country (perhaps thanks to a stronger involvement of KDH activists) and the Hungarian minority. The latter group has been typically quite passive during elections, and in recent years Fidesz, which rules in Budapest, has been gaining influence among them. It is expected that Korčok, before the runoff, will try to demobilise Harabin’s voters, whom Fico will in turn want to attract to Pellegrini. As usual, the ‘last emotion’ voting factor, which has a great impact in Slovakia, will also play an important role – according to local experts, it influences up to 20% of Slovakian citizens eligible to vote in their final decision about whether to vote and for whom.

Pre-election debates are unlikely to change the fate of the campaign. Pellegrini, who is leading in the polls, consistently avoids direct clashes to minimise the risk of mistakes. In the first (and probably the only) discussion between the two frontrunners before the first round, he made no mistakes and even scored points with his rhetorical skills, which are a well-known asset. It seems that only possible moral scandals could somehow shake support for him by demobilising part of his conservative electorate. Matovič has announced that such scandals could be disclosed at the final stage of the campaign.

APPENDIX

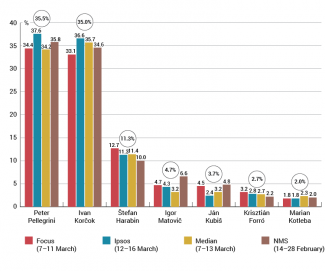

Chart 1. Support for key candidates (latest polls)

The remaining presidential candidates are Patrik Dubovský, Róbert Švec and Milan Náhlik. Andrej Danko (around 1.5–3% of support) withdrew from the race on 18 March and asked his supporters to vote for Harabin.

Source: author’s own estimates based on election models/polls.

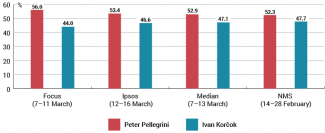

Chart 2. Results of a potential runoff (latest polls)

Source: author’s own estimates based on election models/polls.