Russia’s new large-scale attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure: losses and challenges

Over the past three weeks, Russia has employed a new tactic: targeting Ukraine’s critical infrastructure facilities by aiming to destroy its power plants. This has proved more effective and devastating than the tactics it used in late 2022 and early 2023, when it mainly struck power distribution substations and transmission lines. As a result, Ukraine has lost most of its power generation capacity from thermal power plants and about half from hydroelectric power plants. This has reduced the stability of its power supply, and will probably lead to scheduled outages in the coming weeks. The country’s economic situation, especially the operations of its energy-intensive industrial plants, will also be adversely affected. To address the problem of this energy deficit, the Ukrainian government is considering a plan to create a dispersed power generation network based on small-scale power plants that would provide electricity as well as heat. However, this would require an enormous effort in terms of both planning and carrying out construction work.

The results of the strikes...

On 22 March, Russia resumed its large-scale attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure (see ‘Ukraine: a major blow to the energy sector’). However, compared to the autumn/winter of 2022/23, it changed its tactics: instead of scattered strikes all over Ukraine that mainly targeted parts of its transmission networks, it launched pinpoint, large-scale attacks aimed at destroying facilities that produce electricity and heating: power plants and combined heat and power (CHP) plants. As a result, five large thermal power plants and three hydroelectric plants have been destroyed or severely damaged. The most recent strike on 11 April wrecked the Trypilska Thermal Power Plant, which supplied around 50% of Kyiv’s electricity. Consequently, all the three large units of the state-owned Centrenergo company have either been completely destroyed or are under Russian control. The facilities of DTEK, a company owned by the oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, have also been severely affected. All the units of the Burshtyn and Ladyzhyn power plants have been damaged; the Dobrotvir power plant has also come under attack. On 2 April, DTEK announced that it had lost 80% of its power generation capacity as a result of the Russian strikes.

Map. Ukraine’s largest power plants

Source: the authors’ own compilation based on open access information.

The consequences of the Russian attacks on CHP plants over the past few months have been equally severe. Large urban centres in Ukraine use a centralised heating system which consists of one or several (in the biggest cities) facilities of this kind. The Russian strikes have destroyed CHP plant No. 5 in Kharkiv, which accounted for about half of the city’s heat supply. It will be impossible to rebuild such a large-scale facility before the next heating season starts in the autumn. This will pose a huge challenge for the 1.3 million people currently living in this city. In recent weeks, attacks on such facilities have also occurred in other cities, including Sumy. In the near future, we are likely to see attacks on the remaining CHP plants in Kharkiv and other major cities, with the possible exception of Kyiv, which has more effective missile defences.

...and their consequences

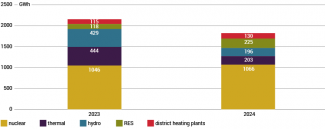

According to the most pessimistic assessments, Ukraine has lost up to 85% of the generation capacity of its thermal power plants and up to 50% of the generation capacity of its hydroelectric power plants as a result of the Russian strikes in March and April. The lost power generation capacity is not the only problem for the government (nuclear power plants still generate more than half of the country’s electricity); the attacks have also damaged the facilities that are responsible for balancing the grid depending on consumption throughout the day. So far this has not resulted in any nationwide power outages, but all the indications are that these will occur in the coming weeks and continue for a long time. Restrictions for the industry have now been put in place in the Kryvyi Rih region and in Kharkiv, which is still struggling to cope with the effects of the attack on 22 March. Two factors have helped to stabilise the situation: record high imports from the neighbouring countries (13,100 MWh on 16 April) and good weather, which has allowed the country to produce more energy from renewable sources. Although up-to-date figures are not available, the attacks in March alone caused a significant drop in power generation by the country’s thermal and hydroelectric plants compared to the previous year (see Chart).

Chart. Ukraine’s electricity production in the first week of April in 2023 and 2024

Source: DTEK.

The situation will deteriorate when the nuclear power plants start shutting down their units for scheduled seasonal maintenance. According to some assessments, Ukraine will then face a power deficit of around 3 GW, even if imports from its neighbours reach their maximum level. It is worth noting that so far the Russian forces have refrained from direct attacks on nuclear power plants, with the exception of incidents at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, which has been under Russian control since March 2022.

Unlike the situation in late 2022/early 2023, rebuilding most of the destroyed facilities will now take between one and several years. Russia’s earlier strikes mainly targeted power distribution substations and transmission lines, while power generation came under fire only sporadically. Russia was attempting to completely destabilise Ukraine’s electricity system in this way; it nearly succeeded on several occasions, but repairing this kind of damage is relatively easy and takes only a few days or weeks if a sufficient stock of spare parts is available. As a result, despite frequent power cuts throughout the country, the system managed to withstand the Russian assault.

Because of Ukraine’s limited missile defence capabilities, Russia’s new focus on its individual power plants has proven to be much more effective. A heated debate has erupted in Ukraine over the effort to defend the country’s electricity system from anticipated Russian attacks. In particular, the government has come under increasing criticism after Russian missiles destroyed the Trypilska Thermal Power Plant (unusually, videos and photos showing the results of the strikes have been posted online). However, these accusations do not appear to be entirely justified, as the fortifications under construction were primarily designed to protect parts of the transmission networks from drone attacks and shrapnel. Putting up defences to effectively protect buildings as large as power plants from the consequences of direct ballistic missile strikes would appear to be an extremely difficult task, if feasible at all.

Prospects

If the Russian attacks cease or become less effective, it may be possible to repair some units of the DTEK-owned power plants. According to some estimates, Ukraine could restore up to 2 GW of capacity in this way before the onset of winter. However, all indications are that it will be impossible to rebuild Centrenergo’s destroyed power and CHP plants before the heating season. There is also the question of whether this would even be reasonable given the new Russian tactics. Increased imports from the EU will not be able to cover the full demand for electricity, as these are limited to a maximum of 1.7 GW; moreover the oblasts located further east, such as Kharkiv and Dnipropetrovsk, cannot be supplied in this way for technical reasons. It is also unclear whether the neighbouring countries will have such large energy surpluses at their disposal, especially in winter.

The government could solve the problem by decentralising production, which would involve the installation of a large number of small-scale (up to 50 MW) gas-fired power plants and generators with capacities of a few megawatts. These have the advantage of being able to cogenerate both electricity and heat, which could fill the gap that Russia’s destruction of Ukrainian CHP plants has left. It remains unclear whether Ukraine could implement such a model on a large scale within a few months, especially as it is unclear who would finance the purchase of such units and then operate them.