Germany: the Hydrogen Core Network Financing Act

On 26 April, the Bundesrat approved the amendment to the Energy Industry Act (Energiewirtschaftsgesetz), which the Bundestag had adopted two weeks earlier. The main part of this amendment was the regulation for financing the establishment of the so-called ‘hydrogen core network’ (Wasserstoff-Kernnetz) in Germany.

According to the adopted concept, the costs associated with the construction and maintenance of the infrastructure will generally be incurred by its users, who will be charged a network fee set by the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA), as is done with natural gas. At the initial stage, the number of users will be small and the costs will be very high. Normally, this would have entailed the need to set an accordingly high fee, which would have made transitioning to hydrogen-based technologies less profitable. To avoid this, a special mechanism will be implemented in order to artificially lower the network fee at the initial stage of the network’s operation. The resulting loss incurred by the network operators will be recorded on a special amortisation account which will be managed by Trading Hub Europe, Germany’s current gas market operator. The account will be funded by loans from the state-owned KfW bank. Over time, as the German hydrogen economy develops, the number of network users is expected to increase, and the costs will be distributed on increasingly favourable terms.

At a certain point, depending on the pace of market development, the revenues from the network fees should begin to exceed the actual current costs. In this way, the initial loss recorded on the amortisation account should gradually decrease. The new act envisages that the account will be closed no later than 2055, and it should also be balanced by that time. If there is still a loss on the account at the time of its closure, the state will cover 76% of the loss (the remaining 24% will be incurred by the network operators). The regulations also provide for the possibility of early closure of the depreciation account at the initiative of the state in case the hydrogen network development proves unsuccessful: the government will not be able to use this option before the end of 2038.

Commentary

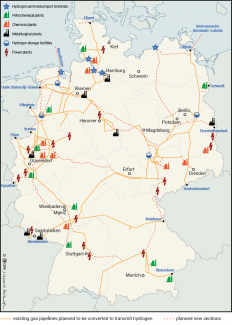

- The hydrogen core network is expected to be the nucleus of the national hydrogen grid, and should connect hydrogen production sites within Germany, as well as import routes (both through pipelines and via seaports), with domestic industrial hydrogen consumers and storage facilities (see map). The Association of Gas Transmission System Operators (FNB Gas) has been tasked with designing the network based on the criteria specified in the act. According to the initial draft presented by FNB Gas last November, the network will be 9700 km-long; almost 60% of it will be based on the existing gas transmission network and will cost a total of €19.8 billion (for more detail see ‘Germany: the next steps in designing the hydrogen network’). The version of the act from November envisioned that the network construction would be completed by 2032: the recent amendment extends this deadline to 2037. In later stages, more sections are planned to be added to the Wasserstoff-Kernnetz based on ‘Network Development Plans’, analogous to those used in gas and electricity infrastructure, which are to be prepared every two years. The first such plan is set to be adopted in 2026.

- The mechanism for financing the hydrogen core network in Germany as outlined in the act has received mixed reactions from the companies that make up the FNB Gas association, who are tasked with building the infrastructure. The network operators do support the amortisation account concept that was initially developed by the German Energy Agency (DENA) in mid-2022, but during the legislative process they raised concerns about some parameters. They argued that these parameters increased the investment risk and made it uncertain as to whether they would be able to secure external financing for individual projects. Their primary demands included changing the level of equity contribution in the final settlement of the account (from 24% to 15%) and raising the return on capital (currently set at 6.69%), to make the model more appealing to investors. After the act was passed, representatives of individual companies reiterated their doubts and announced a reassessment of the investment conditions. Despite these concerns, media reports suggest that politicians from the government coalition do not expect the network operators to withdraw from implementing the hydrogen network, given the fact that they have participated so actively in its planning. According to the act, FNB Gas must make any necessary adjustments to the initial draft, which was presented last November, and submit its final version for approval to BNetzA by 21 May. The agency will then have two months to respond to the application (and may request amendments). Following the agreed schedule and statements from network operators, the first investments could begin by the end of 2024. If FNB Gas fails to submit the application on time, the task of designing the Hydrogen Core Network and finding contractors will automatically fall to the regulator.

- During the legislative process, the size of the planned infrastructure was called into serious question. According to an expert opinion presented by the Fraunhofer Institute, the scale of the network designed by FNB Gas (which was originally envisaged to reach a length of 9700 km by 2032) significantly and unnecessarily exceeds the initially expected demand, which will result in low utilisation rates. These doubts were further compounded by the government’s decision to delay the transition of gas-fired power plants to hydrogen usage from 2035 to the period between 2035 and 2040 (see ‘Key to the future of the Energiewende: support for building new power plants’). In light of these findings, researchers recommended spreading out the infrastructure development over time, a recommendation that was ultimately heeded partly because the network operators themselves had suggested the same. Consequently, the completion date for the Wasserstoff-Kernnetz has been shifted from 2032 to 2037. The authors of the analysis assessed various financing scenarios for the network based on the adopted model of the depreciation account. Their research indicates that in most cases, the network usage fee for infrastructure users should range from 15 to 20 €/kWh/h/a in order to balance the account by 2055. Only under certain adverse conditions (such as very slow market development with higher-than-expected network creation costs) would it need to be raised to 35 €/kWh/h/a.

- The federal government has shown great political determination in preparing the legal framework for establishing a hydrogen network in Germany. One of the main reasons behind the government’s engagement are the interests of the various industrial sectors which are ready to invest in hydrogen technologies. It is also motivated by the model of energy transformation adopted by Germany, where hydrogen is set to play a major role as a backup for renewable energy sources. In addition to regulations regarding the creation of the hydrogen network, in mid-April the economy ministry presented a bill for review under which investments in facilities for hydrogen production, import, transmission and storage are to be given the status of projects of overriding public interest (similar to the provisions adopted for LNG terminals in 2022). This change fundamentally accelerates the resolution of any lawsuits brought against the investments by elevating their legal status compared to other public interests (for example, environmental arguments). Furthermore, Berlin has already been incentivising hydrogen projects in the industry through numerous subsidies (including the use of contracts for difference, the IPCEI mechanism and separate grant programmes for sectors such as metallurgy).

- The pace of development of the German hydrogen sector still raises numerous questions. For example, it remains unclear how many of Germany’s planned hydrogen production projects will actually be implemented, as final investment decisions have not been made for the vast majority of them. Similarly, it is uncertain how many industrial plants will opt for investing in hydrogen technologies; even if they do, it is still an open question as to when and to what extent they will become involved. Predicting the future prices and availability of hydrogen over time is also challenging. Furthermore, there is still a lack of specifics regarding hydrogen imports which, according to government estimates, would cover up to three-quarters of the expected domestic demand. The German government has announced plans to adopt a special strategy for importing hydrogen and its derivatives (such as ammonia) this year. From the industry’s perspective, the lack of clarity on these issues, along with uncertainties surrounding the final shape and timeline for the construction of the transmission infrastructure, is one of the primary barriers to investment. This means that entrepreneurs are still waiting to see how the market will evolve before they decide to implement any projects.

Map. Draft hydrogen core network in Germany, including examples of potential locations of industrial recipients of hydrogen, import terminals and storage facilities

Source: author’s own estimates, Association of Gas Transmission System Operators (FNB Gas).