Germany waters down its climate protection law

On 26 April, the Bundestag passed an amendment to the Climate Change Act (German: Klimaschutzgesetz), which sets out the objectives and mechanisms of Germany’s climate policy; the ruling SPD-Green-FDP coalition voted in favour of it. According to this document, Germany will reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 65% by 2030 relative to 1990, by 88% by 2040, and achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. The law’s previous version set the annual emission caps for individual sectors of the economy (energy, industry, transport, construction, agriculture and waste management) to 2030, and the relevant ministries were responsible for enforcing these caps. If the Council of Experts on Climate Change found that the statutory limits had been exceeded, the ministry in charge of that particular area was obliged within three months to prepare a recovery plan identifying the measures that would ensure a rapid reduction in emissions.

The amendment removes the provisions making individual ministries responsible for progress in decarbonising their respective sectors, in favour of the collective responsibility of the government as a whole. In addition, from now on the council of experts will change its approach to evaluating progress in cutting emissions: instead of assessing the previous year’s data retrospectively, it will prepare an annual, multi-year cumulative forecast for reducing emissions across all the sectors of the economy (first by 2030, then by 2040 and 2045). Only if the analysis finds that the pace of reductions is too slow in relation to the adopted targets for two consecutive years will the government as a whole be obliged to adopt a recovery plan. The Bundesrat must still approve the amendment, which is likely to happen on 17 May.

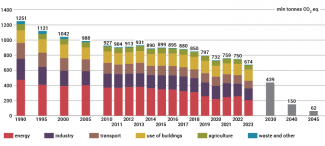

According to the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 stood at 674 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent; this was 46% lower than the figure for 1990, the baseline year for climate policy (see Chart).

Commentary

- The new provisions do not change the medium- and long-term targets for reducing emissions, but they do effectively water down the existing regulations. The law’s previous version, which set rigid emission limits for individual sectors of the economy, put the responsible ministers under pressure from public opinion when these caps were exceeded, and forced them to come up with additional solutions in their areas of responsibility. The shift to the cross-sectoral and collective approach removes responsibility from the heads of individual ministries, which will weaken their determination to take less popular measures aimed at speeding up emission cuts. On the other hand, proponents of this shift have emphasised that a flexible, cross-sectoral approach is more advisable due to the different nature of the individual areas of the economy and the varying availability of technological solutions to reduce emission levels.

- The amendment was adopted as a result of the FDP’s pressure on its coalition partners. Only two sectors of the German economy (use of buildings and transport) have failed to meet their targets for reducing emissions in recent years. In the former case, the annual limits were exceeded only slightly and the trend was positive; in the latter, however, the gap between real emissions and the statutory targets kept growing year by year, reaching 13 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent in 2023. As a result, transport minister Volker Wissing (FDP) has come under fire from the media since the start of his term, especially as he resisted measures that some experts and environmental organisations had suggested, such as introducing a general speed limit on motorways and scrapping tax breaks for cars with internal combustion engines. At the request of the Liberals, the proposal to reform the 2019 law was included in the coalition agreement at the beginning of the government’s term, but the reform was bogged down for months in cross-party consultations due to opposition from the Greens, who criticised it as a measure that would weaken the mechanisms of climate policy. In mid-April this year, Wissing publicly threatened that if the amendment was not adopted quickly, he would be forced to introduce drastic measures such as a ban on driving at weekends in order to meet his statutory obligations. He insisted that the Greens would be responsible for such a scenario. The public outcry caused by this prospect produced the expected result: after a few days of talks, the coalition partners agreed on a final version of the amendment that met the FDP’s expectations.

- The new legislation is highly controversial especially among the Greens and environmental organisations, who have criticised it as a step backwards in climate policy-making. Several influential organisations such as Greenpeace, Deutsche Umwelthilfe, Fridays for Future, Germanwatch, NABU and BUND have issued a joint appeal calling on the Greens to reject the draft and harshly criticising them for making further concessions to the Liberals. Moreover, according to German environmentalists, the new regulations violate Germany’s constitution because they mean that efforts to reduce emissions will be delayed at the expense of future generations. In 2021 the Federal Constitutional Court, citing the same arguments, forced the then CDU/CSU-SPD coalition to tighten the law on climate protection (for more details, see ‘Orzeczenie w sprawie polityki klimatycznej – prezent dla Zielonych’). The BUND organisation, which was the winning plaintiff in that case, has announced that it will commission the same lawyers to explore the possibility of filing another constitutional complaint.

Chart. Greenhouse gas emissions in Germany by sector, and current targets for emission cuts

Source: the author’s own compilation based on data from the Federal Ministry for the Environment.