Germany: green light for the hydrogen network

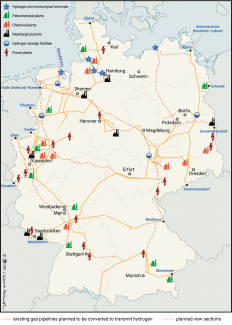

On 22 October, Germany’s regulatory authority, the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur, BNetzA), granted final approval for the draft of the proposed hydrogen core network (Wasserstoff-Kernnetz). This network will establish the backbone of a nationwide infrastructure connecting domestic hydrogen production sites and import facilities, including pipelines and ports, with industrial consumers and storage facilities. According to the approved draft, the network will cover 9,040 km, 56% of which will utilise existing pipelines adapted for hydrogen transport, with the remaining 44% consisting of newly constructed pipelines. The injection capacity at entry points is expected to reach 101 GWth, with extrusion capacity of 87 GWth. The network will be capable of transporting 279 TWh of hydrogen annually.

The network is scheduled for completion by 2032, although the commissioning of individual sections may be delayed until 2037. The project’s estimated cost is €18.9 billion. Additionally, nearly €2 billion will be allocated to the gas network to separate individual pipelines, allowing their conversion for hydrogen transport without compromising the operational stability of the gas system.

According to the criteria established in law, the Association of Gas Transmission System Operators (FNB Gas) was tasked with designing the Wasserstoff-Kernnetz (see ‘Germany: the next steps in designing the hydrogen network’). The final version of the core network is the outcome of extensive consultations involving officials from the BNetzA, federal and state governments, and relevant industries.

In developing the country’s hydrogen infrastructure, the German government has implemented a two-stage approach. The Wasserstoff-Kernnetz, agreed upon extensive consultations, represents the first stage. The core network will be gradually expanded with additional sections based on ‘Network Development Plans’ which FNB Gas will prepare and the BNetzA will approve every two years, mirroring the approach applied to the gas and electricity networks. The first such document, covering both the gas and hydrogen networks, is scheduled for adoption in 2026 (with a draft to be submitted by mid-2025).

A shrinking network

During the nearly two-year planning process, the Wasserstoff-Kernnetz project has been significantly scaled back. The initial plans by gas transmission system operators, based on market modelling and non-binding hydrogen investment declarations, initially envisioned a network extending up to 11,200 km by 2032. However, following the first round of extensive consultations, a preliminary draft presented in autumn 2023 proposed a reduced network of 9,700 km. This draft, with only minor adjustments, was submitted to the regulator for evaluation last July.

In the final planning stage, the network was further reduced by over 600 km, following requests from the BNetzA (for example, to eliminate duplicate sections) and due to investors independently withdrawing certain segments. This decision was primarily influenced by two factors: the need to accommodate the expected slowdown in hydrogen economy growth and the desire to reduce the project’s costs, which future users will ultimately cover through a network fee. To maintain this fee at an affordable initial rate (to be set by the BNetzA in late 2024 or early 2025) and to support the profitability of hydrogen investments, the German government has established a special financial mechanism known as an ‘amortisation account’. This account will be used to temporarily lower the network fee charged to users during the early phase (for further details, see ‘Germany: the Hydrogen Core Network Financing Act’).

Potential adjustments as the hydrogen economy evolves

The BNetzA’s approval of the Wasserstoff-Kernnetz project has authorised network operators to commence the implementation of submitted projects. The commissioning of individual sections, nearly 300 in total, will occur gradually. According to the schedule, the initial sections are anticipated to be operational by mid-2025; with the network expected to span approximately 2,000 km by the close of 2027.

Priority will initially be given to projects granted special financial support under the EU’s Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) mechanism, with €4.6 billion in funding allocated from federal and state government budgets. These projects are mostly located in north-western Germany (Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, and Hamburg) as well as in central and north-eastern regions (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Brandenburg, and Saxony-Anhalt). Among the first pipelines scheduled for conversion in 2025 is an OPAL line, which previously transported Russian gas from the Nord Stream pipeline. Meanwhile, the Leuna refinery will be one of the first industrial plants connected to the network.

Investments slated for completion by 2027 are regarded as secure, with work already in progress for some. For other projects, further modifications remain possible, depending on the pace of development within Germany’s hydrogen economy. Potential adjustments may be incorporated into future network development plans.

A key component of the Energiewende

Developing hydrogen infrastructure is a vital element of Germany’s energy transition strategy (Energiewende). This network is primarily designed to serve industrial consumers in sectors such as chemicals, petrochemicals, steel, paper, and glass, all of which aim to transition to hydrogen-based production processes as part of decarbonisation efforts, replacing fossil fuels. The energy sector is also anticipated to be a major consumer, with hydrogen-fired power plants and cogeneration facilities expected to complement renewable sources in the German system. At this stage, the German government has placed lower priority on hydrogen applications in transport and heating.

Launching the transmission network’s development is also intended to encourage relevant industries to accelerate the hydrogen economy in Germany. To date, the absence of infrastructure has been recognised as a primary obstacle deterring investment in both hydrogen production facilities and hydrogen-based technologies.

A number of uncertainties

The future of Germany’s hydrogen economy remains uncertain. For instance, it is unclear how many of the planned hydrogen production projects will actually come to fruition, as the vast majority still await final investment decisions. Similarly, there is uncertainty regarding how many industrial plants will adopt hydrogen technologies, as well as when and to what extent. It is also challenging to project how hydrogen prices and availability will evolve over time. Furthermore, there are no definitive plans for imports, which, according to government estimates, are expected to fulfil over 50% of projected domestic demand. The government’s hydrogen import strategy, released last summer, failed to address the questions posed by stakeholders (for more, see ‘Germany: the government’s import strategy for hydrogen and its derivatives’). Given these uncertainties, many experts have warned of the risk that the network, which already exceeds anticipated demand (projected to reach 95–130 TWh by 2030), may experience limited utilisation, particularly in its early years.

In recent months, several adverse developments have affected Germany’s hydrogen plans. Following months of behind-the-scenes negotiations, Norway withdrew from plans to construct an undersea pipeline for transporting hydrogen to Germany, while Denmark postponed the completion of a cross-border interconnector at Ellund from 2028 to 2031. Furthermore, one of the largest prospective hydrogen consumers, Thyssenkrupp Steel, is contemplating withdrawing from a project to utilise hydrogen for steel production at its Duisburg plant.

Although enthusiasm for developing the hydrogen economy in Germany has diminished since the early 2020s, Germany’s political and business elites remain resolute in their commitment to hydrogen and are politically determined to pursue this course. Legislative efforts on a specific law aimed at streamlining investments in hydrogen technology and reducing bureaucratic obstacles are now in their final stages.

The government is also anticipated to adopt a hydrogen storage strategy later this year. Finally, it is expected to approve a mechanism (already agreed with the European Commission) to subsidise the construction of gas-fired power plants, which will transition from natural gas to hydrogen following a transitional period of eight years.

Map. The approved draft of Germany’s hydrogen core network includes potential locations for industrial hydrogen consumers, import terminals, and storage facilities

Source: the author’s own compilation, The Association of Gas Transmission System Operators (FNB Gas), The Federal Network Agency (BNetzA).