The prospects for the EU-Ukraine free trade agreement

The European Union and Ukraine initialled the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area Agreement (DCFTA) on 19 July 2012. The scope of the agreement which the EU and Ukraine reached following their negotiations is much more extensive than that of a typical free trade agreement. It envisages not only the lifting of tariff and extra-tariff barriers but also, more importantly, Kyiv adopting EU legal solutions and standards in this area.

Whether the agreement will be signed and implemented is still an open question and depends on the existing political conditions. On the one hand, the repression imposed by the government in Kyiv on its political opponents (including the detention of the former prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko) has provoked criticism from the EU, which refuses to sign the agreement if the government in Kyiv continues to violate democratic principles. The manner in which Ukraine’s parliamentary elections are conducted this October will be the key test. On the other hand, Russia is increasingly active in its efforts to involve Ukraine in the integration projects it has initiated (the Customs Union and the Eurasian Economic Community). It should be noted that Moscow has effective instruments to exert its will, such as the dependence of the Ukrainian economy on supplies of Russian oil and gas and on exports to the Russian market. Besides, Moscow also has political instruments at its disposal.

It is impossible to participate in integration projects both with the EU and with Russia. Therefore, Kyiv will have to make a strategic decision and choose the direction of its economic integration. Unless Ukraine takes concrete action to implement its agreements with the EU, primarily including the free trade agreement, its economic dependence on Russia will grow, and it will be more likely to join the Russian integration projects.

The DCFTA as an instrument of EU policy

The signing of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area Agreement marked the end of the procedure of initialling the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU[1]. The DCFTA is based on two key elements. Firstly, it envisages a liberalisation of trade through lifting customs tariffs, import quotas and other barriers (legal, technical and procedural) to trade. The agreement also states that Kyiv will liberalise regulations on investments and services. Secondly, Ukraine undertakes to adopt EU laws, norms and standards concerning trade under the agreement.

The EU’s priorities in the negotiations concerning the free trade area with Ukraine primarily included: (1) Ukraine’s closer integration with the European market, aimed at improving its political and economic stability; and (2) securing the interests of EU firms and investors by opening up and liberalising the Ukrainian market, and its adjustment to the European model.

The DCFTA is seen as one of the key instruments in Ukraine’s European integration. However, this integration is not understood as offering a perspective of membership, but as Ukraine’s adjustment to the European model, which is expected to ensure stability in the EU’s immediate neighbourhood. The potential economic and business benefits resulting from the creation of the free trade area are expected to serve as an incentive for Kyiv to take effective actions to bring the country closer to the EU. However, the implementation of the Action Plans as part of the European Neighbourhood Policy – and since 2009 of the Association Agenda – has not led to deeper integration[2]. Unlike the preceding instruments aimed at bringing Ukraine closer to the EU (the Partnership and Co-operation Agreement, the Action Plans and the Association Agenda – see Appendix 2), this one introduces mechanisms aimed at mobilising Kyiv more strongly to make real progress with Ukraine’s European integration. The agreement includes a precise schedule for implementing solutions and adopting legislation. Ukraine is also obliged to adjust its legislation on a current basis to any future amendments of EU law, and has no influence whatsoever on the form of such amendments. Should any of the parties fail to comply with the agreement’s provisions, security mechanisms have been introduced, including the suspension of preferences applied, the primary goal of which is to provide the EU with more options to apply pressure on Ukraine. Instruments of dialogue have also been developed, which may contribute to a more effective stimulation of Ukraine’s European integration. Plans have been made to establish a number of expert committees as part of the DCFTA. They will deal with issues regarding co-operation in individual areas of the free trade area’s operation (including sectoral co-operation, customs co-operation, sustainable development, trade facilitations and sanitary and phytosanitary standards).

The issues which are important from the point of view of EU member states include improving the security of European investments and facilitations for doing business in Ukraine. Economic integration as part of the DCFTA is expected to lead to the creation of similar conditions for doing business for both EU and Ukrainian firms. This will be built on the foundation of the regulations and solutions applicable in the EU. As a consequence of removing the mechanisms devised to protect Ukrainian firms and of the introduction of equal conditions for doing business on the basis of EU legislation, firms from EU member states may gain advantage over their Ukrainian competitors. At the same time, in areas where Ukrainian producers might pose a challenge to the interests of EU-based entities (for example in agriculture), the European Union has upheld the mechanisms which restrict the competition they offer, and has preserved the import quotas. Another measure used to secure the interests of EU producers is the protection of intellectual property rights (including trademarks and geographical marks). Special procedures for dispute resolution have also been introduced. They will offer better protection than now for the rights of EU member states and companies operating in Ukraine (and vice versa).

The economic impact

From the economic point of view, the implementation of the DCFTA agreement will primarily be significant for Ukraine. This is due to the huge disproportion existing between these two markets – the EU with 500 million consumers, the world’s largest market, the nominal value of whose GDP in 2011 reached US$17.6 trillion on the one hand, and the Ukrainian market, which is less than one-tenth times the size in terms of the number of consumers, and which generated a GDP at a level of US$165 billion (54th in the world)[3]. Economic co-operation is much more important for Ukraine than it is for the EU. While for Ukraine the European Union is the second largest trade partner after Russia (in 2010, the EU accounted for 28.6% of the trade), Ukraine is of secondary importance for the EU (being only the 22nd largest trade partner, with a share of 1.1% in trade)[4]. To a great extent, Kyiv had to accept the conditions set by the EU in the DCFTA; the room for negotiation was limited. The implementation of this agreement, which provides for part of the acquis communautaire to be adopted by Ukraine and the liberalisation of trade and investment regulations, will not bring any changes into EU legislation. The agreement will have an impact not only on the trade co-operation between Ukraine and the EU, but also on the operation of Ukraine’s entire internal market[5].

The estimates published so far, based on the calculations made according to the computable general equilibrium model[6], point to a potential increase in cumulative welfare gains[7] for Ukraine in the long term at a rate between 4% and 11%[8]. In turn, in the case of the EU, this indicator will not exceed 1%[9]. However, it has to be emphasised that these calculations are based on a model which does not consider a number of essential factors (for example, the impact of the crisis in the eurozone, or possible changes in Ukraine’s political and economic situation), or certain details of the provisions under the DCFTA agreement. Therefore, they can only be interpreted as indications of a potential trend in the change of the situation, and not as an accurate forecast of change.

There is no comprehensive evaluation of the impact the implementation of the DCFTA agreement will have on individual sectors of the economy. Those analyses which have been published have considered Ukraine only partially, while the impact on the individual sectors of the EU market has not been examined. According to the estimates presented so far, the branches of the Ukrainian economy which could benefit from the agreement in the long term include the clothing, wood, metallurgical, food (food production) and machine-building industries. In turn, the agriculture, service and light manufacturing sectors may face a decrease in income. However, the evaluations in this context vary. For example, agriculture is mentioned among the sectors which will lose most[10], while some simulations indicate that food manufacturers could increase their incomes by €393 million in Ukraine and €860 million in the EU[11].

The potential benefits for Ukraine…

Lifting the customs tariffs alone, without a deep and comprehensive legislative harmonisation, would have had a much weaker impact on the Ukrainian economy, given the trade preferences the EU has already granted to Ukraine (as part of the WTO and the Generalised System of Preferences; for more details, see Appendix 2) and the relatively low customs tariffs. Economic integration with the European Union potentially offers Ukraine access to the EU market, and may also provide it with greater opportunities for extending its exports to global markets (partly owing to the adoption of the EU standards in production and services). At the same time, this will boost competitiveness on the domestic market, which will be beneficial to Ukrainian consumers.

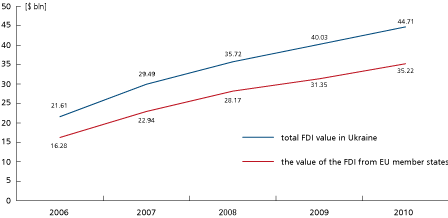

The legislative harmonisation with the EU will bring about a better operation of the Ukrainian legal system and will also curb corruption. It may also lead to an improvement in the business climate, and thus create more opportunities to gain access to new sources of financing (including foreign direct investments and foreign loans; the loan costs will also be reduced). The transfer of new technologies and management methods will improve production efficiency and quality. The improvement of investing conditions is essential because Ukraine has been evaluated as the country with the worst business climate in Eastern Europe[12] and with the highest level of corruption[13]. The European Union is one of Ukraine’s most important trading partners, and investments from EU member states clearly predominate among the foreign direct investments: in 2010, their share reached 78.8%[14].

The increasing competition from EU-based firms may also turn out to be an effective stimulus for the Ukrainian economy to undergo reforms and modernisation. One example may be the need to improve energy efficiency, and thus to reduce the production costs of Ukrainian firms so they can come up against the competition offered by EU-based firms. Other examples may be the reduction of dependence on oil and gas imports, and the diversification of the sources of economic growth, which now relies on large raw-material corporations (for example, from the metallurgical sector), through the development of other branches of the economy, such as the service sector and the small- and medium-sized businesses sector.

…and the real challenges

However, implementing the DCFTA entails a need to make a great administrative effort (in connection with the implementation of the acquis communautaire) and to spend the funds (by the state and firms alike). The Ukrainian government has not as yet publicised the precise and total costs of implementing the agreement[15].

The increase in production costs resulting from the introduction of EU standards may make Ukrainian entities less competitive at the initial stage of the agreement’s implementation. This will be primarily a challenge for small and medium firms, some of which may face bankruptcy. The large corporations controlled by Ukrainian oligarchs will be affected less; these export their products to the EU market because they have already taken actions to adapt to EU standards (for example, production and ecological standards). However, this is not linked to the adoption of the DCFTA, but to their activity on the European market[16].

The EU’s offer, which could compensate for the costs incurred by Ukraine, is rather limited. Apart from the potential benefits in the long term, which have not been precisely defined, no short-term benefits have been clearly indicated. The Association Agreement and the DCFTA do not envisage any significant increase in financial or technical support from the EU in addition to what has already been offered as part of the Eastern Partnership, the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument, and other EU facilities (for example, the programmes of the European Investment Bank and the EBRD). At the same time, it is now uncertain whether the EU will be able to offer more aid in the future, due to the eurozone crisis, and the desire of some member states to cut the European Union’s spending (especially as the Eastern Partnership is not a high priority for the EU member states). Ukraine may also have problems with the costs of implementation of the DCFTA, due to mounting economic problems and the slowdown in economic growth (according to the IMF’s estimates, Ukraine’s GDP in 2012 will grow by 3.0%, while in 2011 it grew by 5.2%[17]; in the first half of 2012 industrial production increased by as little as 0.7%). Integrating the Ukrainian economy with the large and competitive EU market requires political will and a far-reaching vision. Kyiv will find it challenging to cope with the strong competition and use its emerging opportunities by developing new sectors. One example may be the IT service outsourcing sector, where exports in 2011 reached the value of US$1 billion and annual growth was between 30–40% (the sale of exports in this sector was higher than that of weapon exports, which traditionally generate high profits)[18].

However, an essential discrepancy in the expectations and interests is emerging between Kyiv and Brussels. Implementing the DCFTA could bring Ukraine potential benefits in the long term, which however requires it to incur significant costs now. In turn, for the Ukrainian political elite, the most important thing are temporary political and economic profits, which the implementation of the agreement does not guarantee. Ukraine is also becoming more sceptical due to the uncertainty about which direction the EU will be developing in regarding the crisis in the eurozone. The lack of any prospect of membership is also frequently raised. Some ask what the point is in implementing a significant part of the EU acquis if Ukraine will not have any influence on its form and will not be able to benefit fully from it.

The political background

From the Ukrainian government’s point of view, the implementation of the DCFTA agreement is not connected with any tangible current political benefits. The top priority issues at this moment for Kyiv are the upcoming parliamentary elections and vying with the opposition on the internal political scene. European integration, including the free trade zone, are not seen as the most important issues by Ukrainian voters. For this reason, whether the Association Agreement is signed or not will not have any major impact on the outcome of the election or on the internal political competition. Besides, it is the present cabinet led by Mykola Azarov who can take the credit for accelerating and finalising these negotiations. The previous governments, including the Yulia Tymoshenko cabinet, were unsuccessful with this.

The Ukrainian government initialled the DCFTA because it wants to continue the dialogue with the European Union and to avoid isolation, even though mutual relations are worsening due to the continued imprisonment of Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister and opposition leader, as well as the violation of democratic standards in Ukraine. A failure of the negotiations or withdrawal from the implementation of the agreement would mean a breakdown of the process of integration with the EU. This could have serious geopolitical consequences for Kyiv and would significantly weaken its position in dealings with Russia, which desires to strengthen its influence in Ukraine. The gestures which suggest engagement in the European integration process are an attempt at breaking the political deadlock in relations with the EU. The Ukrainian government put the negotiations concerning the DCFTA agreement on a faster track at the beginning of 2011; owing to this, it was possible to conclude the negotiations in December 2011. The fact that on 20 March 2012 the Ukrainian parliament adopted a resolution to implement the DCFTA agreement as soon as possible, immediately after its signing and before its ratification (which is admissible under EU law) – upon the initiative of the ruling Party of Regions – can be seen in the same context. At the same time, despite the crisis in political relations, Ukraine has been gradually carrying out its tasks set under the Association Agenda. While regress has been observed in the areas of political reforms and democracy[19], moderate progress has been seen in the economy and sectoral reforms (42 of the 48 priorities set for 2011–2012 are being implemented, 3 have been completed and 3 have not been carried out)[20]. However, this does not mean that the Ukrainian government is fully engaged in introducing EU regulations. Kyiv often disregards the EU’s stance when it is at variance with the interests of local lobbies. For example, on 1 August 2012, President Viktor Yanukovych signed a law under which the obligation to hold tenders for the purchase of goods and service was lifted from state-controlled companies in cases where they purchase these using their own funds. This decision has been criticised by the EU as contrary to the provisions of the Association Agreement[21]. Another factor which undermines the Ukrainian government’s will to implement the DCFTA is the deteriorating economic situation in Ukraine. To protect its own market and increase budget revenues, the Ukrainian government in mid-September this year notified the WTO’s members of its intention to raise customs tariffs on over 350 goods[22]. The EU has voiced concerns that this decision could affect its exports to Ukraine, and is contrary to the guidelines of the free trade agreement.

Although the Ukrainian government has declared that it will grant high priority to integration with the EU, Kyiv has been trying to conduct a policy of balance between Brussels and Moscow, and win benefits from both sides. This policy is primarily aimed at achieving short-term results and not long-term goals. Russia has been increasing the pressure on Ukraine to join the reintegration projects it has initiated in the former USSR: the Customs Union and, in the longer term, the Eurasian Economic Community. Moscow has strong instruments of influence, principally Ukraine’s dependence on oil and gas supplies from, and exports to, the Russian market. Kyiv is making efforts to renegotiate its unfavourable gas contract and reduce the gas price (which is one of the highest in Europe). In an attempt to capitalise on this, Russia is threatening to take retaliatory action if Kyiv joins the free trade area with the EU, and Ukraine will suffer economic losses as a consequence. Moscow has also been pressing on Ukraine to withhold carrying out its obligations as part of the Energy Community, which envisage the adoption of EU directives concerning the gas sector, electric power, renewable energy and environmental protection[23]. Although the Association Agreement and the DCFTA are separate from the Energy Community agreements, the provisions of the DCFTA include references to the provisions and actions being implemented as part of the Energy Community. Ukraine’s possible withdrawal from the Energy Community will not formally mean a suspension of the DCFTA implementation, because these are two separate legal acts. However, if Kyiv took such a decision, it would face political consequences; it would mean the failure of the energy integration programme, and would call into question Ukraine’s will to implement the provisions of the Association Agreement and the free trade agreement, and thus its desire for European integration.

Ukraine is not interested in participating in Russian integration projects as yet. However, as political relations with Brussels deteriorate, it cannot be ruled out that Kyiv will redefine the vectors of its economic policy and choose closer co-operation with Russia. More and more opinions can be heard which are critical of integration with the EU and opt for improving co-operation with Russia, one example of which is the intensifying political activity of Viktor Medvedchuk, the former head of Kuchma’s presidential administration[24].

What next for the DCFTA?

The initialling of the entire DCFTA document, which has gone almost unnoticed, technically ends one stage in the negotiations on the Association Agreement. Before the agreement comes into effect, it must be signed and then ratified. Some member states are pressing the Commission to enable temporary implementation of the DCFTA after it has been signed (which is possible within a timeframe of between one and two years) but before its ratification (which can take place within three or four years at the earliest). However, EU-Ukraine relations are deadlocked now due to the detention of Yulia Tymoshenko. The future of the Association Agreement of the DCFTA will strongly depend on how the parliamentary elections in Ukraine, which are scheduled for 28 October, proceed; the EU will not take any strategic decisions before then. If the Ukrainian government continues to violate democratic standards, the European Union’s consent to the implementation of the DFCTA will be very unlikely.

Appendix 1

The DCFTA guidelines

- lifting customs tariffs (import and export) on goods manufactured in the EU and Ukraine

In the case of some goods, tariff reduction is to be carried out gradually within a timeframe of up to ten years. Ukraine has maintained the option to use protection mechanisms on certain conditions within fifteen years of the beginning of the agreement’s implementation, including imposing export duty on certain goods or keeping higher import duty on selected goods (for example, cars).

- removal of technical barriers to trade and import restrictions (with the exceptions admissible under the GATT[25] rules)

The EU has maintained quotas in the case of some agricultural and food products imported from Ukraine (for example, meat and dairy products), and Ukraine has done likewise for those imported from the EU (for example, pork, poultry and sugar).

- Ukraine’s adopting EU regulations, standards and laws in the area of trade

The agreement includes a schedule for adopting individual EU regulations, including those concerning sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical regulations, customs procedures, investment law and the rules for operation of foreign companies, competition rules, state aid to business entities, principles which regulate the operation of some branches of the service sector, including financial services, telecommunication, maritime transport, postal services, etc.

- introducing the same rules for trade between the EU and Ukraine as those existing between the EU member states

These issues are to be regulated under the Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance of Industrial Products (ACAA)[26], which is to be attached to the DCFTA as an additional protocol. In the case of Ukraine, the ACAA is intended to cover selected branches of the industry (but not the entire economy), and envisages the adjustment of Ukrainian technical and infrastructural regulations and standards to EU legislation.

- equal conditions for doing business for business entities

Each party is to ensure the freedom to do business for companies from the other party operating in its area on the same terms as enjoyed by its own companies, and to refrain from discriminatory practices, with the exception of certain sectors (including mining, the arms industry, and maritime and air transport). This also concerns public procurement, where both parties are expected to treat business entities as their own, and Ukraine is supposed to gradually adjust its regulations to those applicable in the EU. At the same time, Ukrainian regulations concerning the flow of capital and investments are to be liberalised.

- protection of intellectual property rights and geographical indication

The list of protected names of goods includes approximately 3000 products from the EU (for example, cognac and champagne) and approximately 100 from Ukraine.

- dispute settlement procedures

These should have a greater influence than before on the other party in cases where provisions of the agreement are breached, and also in cases when the rights of entrepreneurs operating on the other party’s market are violated. This is a serious problem now, especially with regard to securing the rights of firms from EU member states operating on the Ukrainian market.

- the energy sector

The free trade agreement refers to a smaller extent to energy co-operation, the basis for which is the agreements concluded as part of Energy Community. The DCFTA is primarily focused on issues concerning trade in energy and raw energy materials (setting prices, customs duties, infrastructural co-operation, and the transit and transport of energy). It is assumed that Ukraine will liberalise its energy prices. The provision-setting guarantees for the secure transit of energy raw materials are vital for the EU. Ukraine has undertaken to improve its own gas transit regulations. However, the provision on safe transit will have limited consequences, since none of the parties is able to influence the actions taken by third parties – in this case Russia, which is the key supplier of the oil and gas which are transported to the EU through Ukraine.

- the dialogue instruments

The agreement provides for the establishment of export committees and dialogue forums to handle individual areas of co-operation covered by the DCFTA.

Appendix 2

EU-Ukraine trade relations

EU-Ukraine trade relations are now based on the Partnership and Co-operation Agreement (PCA), which was signed in 1994 and came into force in 1998. Among other things, it provides for lifting limitations for preferential trade (including the use of discriminative tariffs and import quotas) and bringing Ukrainian legislation closer to the rules of the EU’s common market. The European Union also granted Ukraine ‘most favoured nation’ status[27], as a consequence of which it received preferences similar to those the EU granted to the member states of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). In 1993, Ukraine was included in the EU’s Generalised System of Preferences (GSP), which made it easier for developing countries to export some categories of goods to the EU market[28]. It is worth mentioning at this point that other eastern partners were offered more favourable trade conditions over time. For instance, Moldova was covered by Autonomous Trade Preferences (ATP), which lifted EU customs duty on almost all goods with the exception of some agricultural and food products. In turn, the Southern Caucasian countries were covered by the GSP+ system, which set the customs tariffs at a lower level than in Ukraine’s case. Although the GSP preferences extend to less than a fourth of total Ukrainian exports to the EU, the ration of their use by Ukraine is high: in 2010 it reached 72.2%, and the value of exports as part of the GSP stood at €2.15 billion[29] (the total export value being €9.94 billion[30]).

Action Plans, whose aims include bringing Ukrainian regulations closer to EU solutions, were introduced in 2004 as part of the European Neighbourhood Policy. In 2009, the Actions Plans were replaced with the Association Agenda, which is a transitional European integration instrument, applicable until a new Association Agreement comes into force.

Ukraine’s accession to the WTO in 2008 was another step in trade liberalisation with the EU. Ukraine has reduced its customs tariffs on EU products and has gradually limited some export duties to the EU, among other measures. Pursuant to the agreed schedule, Ukraine’s average customs tariffs in 2013 will be 5.1% (10.1% on agricultural products and 4.8% on industrial products)[31].

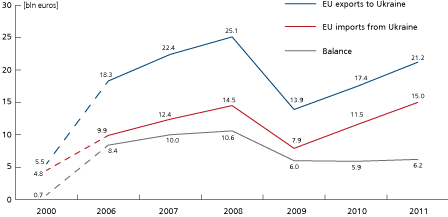

The trade volume between the EU and Ukraine was growing regularly until 2009, when the financial crisis led to significant reductions in both Ukraine and the EU. In 2011, this value reached €36.17 billion, including EU exports to Ukraine totalling €21.2 billion, and imports of €15 billion. There is also a strong asymmetry in relations between these two parties. While the EU is Ukraine’s second largest partner after Russia (it accounted for 28.6% of the trade in 2010), Ukraine is of low significance for the EU (the 22nd biggest trade partner, with just 1.1% share in trade)[32].

1. Value of trade between the EU and Ukraine (in billions of euros)

Source: European Commission’s Directorate General for Trade (DG Trade)

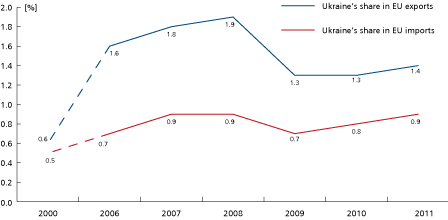

2. Ukraine’s share in the EU’s trade

Source: European Commission’s Directorate General for Trade (DG Trade) and Eurostat

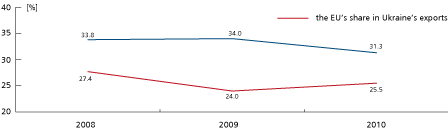

3. The share of EU member states in Ukraine’s trade

Source: European Commission’s Directorate General for Trade (DG Trade) and the International Monetary Fund

4. EU Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in Ukraine (US$ billions)

Source: State Statistical Service of Ukraine (Ukrstat)

[1] The negotiations of the two agreements ended in December 2011, and the Association Agreement and the first and the last pages of the DCFTA Agreement were initialled on 30 March 2012

[2] Katarzyna Pelczynska-Nalecz, ‘Integration or imitation? EU policy towards its Eastern Neighbours’, OSW Studies, 2011, http://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/PRACE_36_en.pdf:

Julia Langbein, Kataryna Wolczuk, ‘Convergence without membership? The impact of the European Union in the neighbourhood: evidence from Ukraine’, Journal of European Public Policy, 2011.

[3] According to data from the International Monetary Fund for 2011, the nominal GDP value of all EU member states reached US$17.6 trillion, and the four largest national economies were as follows: 1. the USA with US$15.1 trillion, 2. China with US$7.3 trillion, 3. Japan with US$5.9 trillion and 4. Germany with US$3.6 trillion; http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/01/weodata/index.aspx

[4] Data on the basis of information from the Directorate General for Trade (as quoted by Eurostat and the IMF) http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113459.pdf

[5] Iana Dreyer, ‘Trade Policy in the EU’s Neighbourhood’, Notre Europe, 2012.

[6] Computable general equilibrium model (CGE) – an economic model which on the basis of current economic data estimates the impact of selected factors (political, technological, legislation changes, etc.) on changes in the economy.

[7] So-called cumulative welfare gains: this indicator evaluates the level of social welfare depending on actions taken as part of public intervention (for example, social benefits resulting from trade policy).

[8] Marek Dabrowski, Svitlana Taran, ‘Is Free Trade with the EU good for Ukraine?’, CASE Network E-briefs, no. 06/2012, March 2012.

Veronika Movchan, Volodymyr Shportyuk, ‘Between two unions: optimal regional integration strategy for Ukraine’, 13th Annual Conference of the European Trade Study Group, Copenhagen, August 2011.

ECORYS, Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment for the FTA between the EU and Ukraine within the Enhanced Agreement, Report for the European Commission DG Trade, December 2007.

[9] The data published by Veronika Movchan and Volodymyr Shportyuk, which already took into account the change in the Ukrainian tariffs following accession to the WTO, indicated that welfare gains in Ukraine would increase by 4.3% in the short term and by 11.8% in the long term. Veronika Movchan, Volodymyr Shportyuk, ‘Between two unions: optimal regional integration strategy for Ukraine’, 13th Annual Conference of the European Trade Study Group, Copenhagen, August 2011.

[10] Michael Emerson ed., ‘The Prospect Of Deep Free Trade Between The European Union And Ukraine’, Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels 2006, pp. 213.

[11] Olexandr Nekhay, Stephan Hubertus Gay, Thomas Fellmann, ‘A Free Trade Agreement between Ukraine and the European Union: Challenges and Opportunities for Agricultural Markets’, EAAE 2011 Congress, Zurich, 2011, pp. 8.

[12] In the 2012 Doing Business ranking, which examines the conditions for doing business, Ukraine was ranked 152nd out of the 183 countries in the world, the lowest in Eastern Europe, http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings.

[13] In Transparency International’s corruption perception ranking for 2011, Ukraine was ranked 152nd out of the 182 countries in the world; this being the lowest position in Eastern Europe, http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2011/results/

[14] Data provided by the State Statistical Service of Ukraine (Ukrstat). However, it should be noted that firms registered in Cyprus accounted for the largest share of investments (28.1%), which means that Ukrainian and Russian capital is being reinvested. Nevertheless, these firms are operating according to EU law.

[15] Some fairly general cost estimates have already been published by various research centres, such as ‘Costs and Benefits of FTA between Ukraine and the European Union’, Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting, Kyiv, 2010.

[16] Kateryna Zarembo, ‘EU-Ukraine DCFTA: What do oligarchs think?’, Institute of World Policy, Policy Brief no. 1/2012.

[17] International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook: Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth, October 2012, pp. 79.

[18] Graham Stack, ‘Tapping Ukraine’s IT potential’, Financial Times beyondbrics, 22 August 2012, http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2012/08/22/tapping-ukraines-it-outsourcing-potential/#axzz24MArDC9C

[19] Звіт № 4 за результатами Громадського моніторингу виконання пріоритетів Порядку денного асоціації Україна – ЄС (січень-вересень 2011 року), Громадський моніторинг Порядку денного асоціації Україна-ЄС, 2011, http://www.ucipr.kiev.ua/files/books/Report4_monitoring_PDA%28Jan-Sep2011%29.pdf

[20] Виконання Порядку денного асоціації Україна – ЄС: чи є прогрес у секторальних реформах?, Інституту економічних досліджень та політичних консультацій (ІЕД), 2012, http://www.ier.com.ua/files/Public_events/2012/AA_Economy_Nov2011_May2012_Report_IER_ukr.pdf

[21] Dmytro Shurkhalo, ‘Влада виправдовує «тінізацію» держзакупівель турботою про держпідприємства’, Radio Svaboda, 16 August 2012, http://www.radiosvoboda.org/content/article/24679447.html

[22] Formally, Ukraine has announced the launch of the procedure to renegotiate the customs duty rates agreed within the WTO. It has also assured that the EU’s interests will not be affected, and the customs duty rate changes will not apply to trade with the EU.

[23] For more on Ukraine’s engagement in co-operation as part of the Energy Community see: Wojciech Kononczuk, Slawomir Matuszak, ‘Ukraine & Moldova and the Energy Community’, OSW, EastWeek, 28 March 2012, http://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/eastweek/2012-03-28/ukraine-moldova-and-energy-community

[24] Viktor Medvedchuk’s interview for Glavcom portal, 12 July 2012, http://glavcom.ua/articles/7597.html

[25] General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

[26] Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance of Industrial Products. Although Ukraine has promised since 2005 to enter into this agreement and to implement its provisions, it has made rather limited progress in the negotiations and the adoption of its guidelines.

[27] ‘Most favoured nation’ status provides the country it is granted to with trade preferences in the form of low customs duties and/or high import quotas. These preferences may not be smaller than those offered to any other country which the country granting the status keeps trade relations with.

[28] Including machines, mechanical parts, chemical products, textiles, base metals and some plants.

[29] Data as provided by the Directorate General for Trade http://ec.europa.eu/trade/

[30] Data as provided by the International Monetary Fund.

[31] ‘Costs and Benefits of FTA between Ukraine and the European Union’, Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting, Kyiv 2010, pp. 23.

[32] Data on the basis of information from the Directorate General for Trade (as quoted by Eurostat and the IMF) http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113459.pdf