New market conditions and “exit strategies“ for the German arms industry

Due to changing internal and external conditions, the German arms industry is facing serious challenges as are its counterparts across Europe. The arms sales market in Germany is contracting – orders from the Bundeswehr are slowing down and the Federal Ministry of Defence is planning to change the way it cooperates with German arms producers. In addition, member states of NATO and the EU, major customers of German arms manufacturers, are reducing their defence spending, which will spell a fall in their orders for new armament and military equipment. In response to the new circumstances, the German arms industry is beginning to organise itself and increase its lobbying efforts in Berlin and, with the support of the federal government, it has been implementing specific measures in several areas. German companies are interested in securing new markets outside NATO and the EU and are also exploring opportunities for mergers and joint ventures with other German and foreign companies, and are seeking to create more conducive conditions for business on the EU and NATO markets.

The arms industry in Germany

In Germany, the arms industry is defined as a part of security and defence industry (Sicherheits- und Verteidigungsindustrie)[1]. It includes companies producing for the needs of civil security and of national defence. It encompasses both the production of security systems e.g. for public spaces (sports facilities, large-scale public events), national borders (e.g. airports and border crossings), and critical infrastructure, as well as armament and military equipment. By presenting the arms sector as a part of a broader branch of industry, the unpopular “arms production” in Germany is rhetorically “concealed”, and the needs of the German companies supplying both the military and the civilian sectors and using military technologies in civilian production and vice versa are addressed. It is worth noting that German arms-producing companies are privately owned, with the exception of Airbus Group (formerly EADS). The German government holds a 12% stake in the group and manages its shares via the state-controlled KfW bank. The federal government has however the right to oversee and even veto any transaction in which an investor from a third country (outside the EU or EFTA) seeks to acquire more than a 25% stake in a private German arms company (if it is denoted as being of strategic importance).

The German arms industry is characterised by a high degree of diversity. Among the largest arms-producing companies manufacturing complete systems are a group of firms included in the 2012 SIPRI list of the world’s 100 largest arms producers[2]. These are German subsidiaries of two European conglomerates: Airbus Group (including Airbus, Airbus Defence & Space, and Airbus Helicopters)[3] and MBDA (MBDA Deutschland), as well as several German companies: Rheinmetall Defence, ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS), Krauss-Maffei Wegmann (KMW) and Diehl Defence. The largest German arms-producing companies also include the engine and propulsion systems manufacturers MTU Aero Engines and MTU Friedrichshafen, the well-known firearms manufacturer Heckler & Koch, as well as the shipbuilding company Lürssen Defence, which narrowly missed out on inclusion in the SIPRI list. It is also worth mentioning that the arms industry includes small and medium-sized companies that excel in niche military technologies (they tend to also operate on the civilian market). Such firms include OHB-System (design, construction and installation of satellites), Carl Zeiss (optical systems), Rohde-Schwarz (electronic test equipment, broadcasting equipment, detection systems), Plath (radiolocation, radio reconnaissance), ESG (information, communication and navigation systems), Atlas Elektronik (maritime systems and electronics). The significance of these firms is evidenced by a joint policy on small and medium-sized security and defence companies agreed on by a group of German trade associations in March 2013[4]. Some of Germany’s largest “civilian” companies also sell products and technologies to the military. Among them are Mercedes Benz (chassis), Daimler (chassis, lorries; a majority shareholder of MTU Friedrichshafen), SAP and IBM (software, databases), Kärcher (decontamination systems, field kitchens) and Siemens (telecommunications and IT systems, amongst others)[5].

The German arms industry is also characterised by a large network of links with foreign companies in NATO and EU member states as well as in equivalent countries[6]. (1) The first group includes German subsidiaries of Airbus Group, which cooperate closely with Airbus subsidiaries in other EU countries on such joint projects as: the Eurofighter, the A400M transport aircraft, the NH90 medium-size transport helicopter, and the Tiger combat support helicopter. This group also includes MBDA Deutschland, a subsidiary of the European MBDA group, which has been involved in some of the projects run by its parent company. (2) The second group includes German companies (as well as German subsidiaries of Airbus Group and MBDA Deutschland), which establish joint ventures with foreign firms (including European, US and Israeli firms) for specific projects[7]. (3) The third group includes companies such as MTU Aero Engines and MTU Friedrichshafen, as well as small and medium-sized German firms, which supply subsystems for foreign companies, in Europe and beyond.

There is little reliable data on the impact of the security and defence industry on Germany’s economy. According to the BDSV, in 2011 the companies in this sector directly employed 100,000 people and generated another 120,000 subcontracting jobs. Their output in 2011 was worth 21.3 billion euros, or 1% of Germany’s GDP. Between 2005 and 2011, the production value of the broadly defined industry grew by 6% – compared to a growth of 0.8% in the narrowly defined arms sector. Similarly, employment figures for the same period showed a 5.3% increase for the whole industry, while the narrowly defined arms sector recorded a 0.4% drop in employment. It should be noted that the BDSV has been laying emphasis on the above average level of innovation among the companies (compared to other industries in Germany).

Domestic and foreign markets

The German arms industry offers a wide range of cutting-edge military products. Among them are complete systems for both ground troops (tanks, self-propelled howitzers, infantry combat vehicles, armoured personnel carriers, firearms and ammunition), for the navy (submarines, minesweepers, patrol ships, boats, corvettes, frigates) and for the air force – under European cooperation programmes (combat and transport aircraft, helicopters). It also produces a range of components and subsystems. In 2007 the Federal Ministry of Defence and Federation of German Industries agreed a list of national technological and production core capabilities for Germany’s arms industry, which should not be abandoned because of their relevance for Germany’s security, industrial, technological and armament policies[8]. By defining the core capabilities, the industry hoped to secure the (financial) backing of the federal government, which would in turn allow the companies to draft long-term business plans. At present, the industrial lobby is calling on the federal government to update the above mentioned list and to de facto commit itself to protecting and supporting the key national capabilities. They argue that the list needs to reflect changes in both the Bundeswehr and the arms sectors across all NATO and EU member states.

The Bundeswehr has been the most important customer of the armament and military equipment produced by German companies, as seen in the statistics compiled by the BDSV. In 2011, just 17% of the defence industry’s output was exported. The ratio of imports to production remains very low (3%), which means that the needs of the Bundeswehr and of federal and regional security agencies (police, special services) are met mainly by the domestic companies. Furthermore, the Bundeswehr has financed large-scale research and development projects which allow German companies to design cutting-edge military equipment. Once purchased by the German Armed Forces, the equipment is used as a reference product in contract negotiations with foreign customers. This means that the level of support the federal government is likely to offer to German arms manufacturers is influenced by the future needs of the Bundeswehr. In the short- to mid-term, the Bundeswehr will require (reconnaissance and armed[9]) medium-altitude long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles (MALE UAVs), modernisation of its medium-range air and missile defence system, Joint Support Ships, MKS 180 multi-role combat ships, a successor to the CH-53 heavy-lift helicopter, and a successor to the Transall C-160 tactical transport aircraft. Some of the projects are already being implemented while others are likely to require technological and manufacturing collaboration with foreign companies. With regard to future purchases by the Bundeswehr, it should be noted that until 2020 up to 90% of the defence procurement budget will be spent on existing large-scale armaments projects (incl. Eurofighter, A400M, NH90, Tiger). Consequently, probably no new projects of this size will begin before 2020.

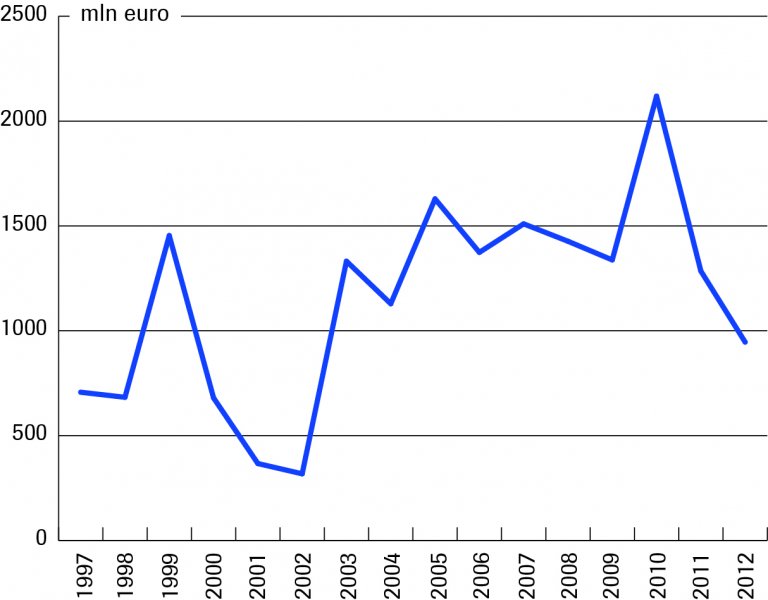

According to federal government figures, since 2005 Germany has been exporting arms worth 1-1.5 billion euros a year. The figures show a steady decline over the past three years, with the exception of unprecedented sales in 2010 (worth 2.1 billion euros due to Germany’s submarine sales to Portugal and Greece). However, the actual value of German arms exports is difficult to establish because the relevant data published by the federal government is incomplete. Although the annual federal government reports contain information about the value of arms exports (Kriegswaffen – complete systems, firearms, missiles and ammunition), they do not specify the value of the export of other equipment (Ausrüstungsgüter – parts, components, subsystems). However, non-governmental sources suggest that the export of German electronic and optical products, as well as simulators, engines and propulsion systems for military purposes is becoming increasingly significant. It therefore follows that broadly defined exports of German military products are much larger and are not necessarily in decline (as the figures for exports of complete military systems would have us believe). Interestingly, despite a drop in arms exports between 2010 and 2011 (according to federal government data), all major arms manufacturers in Germany have reported growth in the sale of armament and military equipment (based on figures published by SIPRI). There has also been a change in the destination of German arms exports. Until recently, 60-75% of German arms (based on value) were sold to countries of NATO, the EU and equivalent, with the remainder being sold to third countries. In 2011, the ratio reversed – with just 32% of arms exports heading NATO, EU and equivalent markets, and as much as 68% being purchased by third countries. This trend was observed also in 2012 – 41% and 59%, respectively, which might reflect a new export strategy of German arms manufacturers.

New market conditions and “exit strategies“

Due to changing internal and external conditions, the traditional German arms industry is currently facing a series of challenges[10]. Germany’s domestic market is contracting and the procurement procedures of the Federal Ministry of Defence are under review. This is directly linked to a reform of the Bundeswehr currently underway, which is aimed at bringing down the number of personnel and thus reducing current and future defence procurement. Furthermore, the federal government is planning to change the way it cooperates with German arms manufacturers (whose main customer it has been). The Bundeswehr is expected to cut back on the volume of armament and military equipment it purchases in the future. It is instead going to focus more on “off-the-shelf” products and technologies, while new long-term projects are likely to be financed less frequently or more rationally. The members of NATO and the EU are reducing their defence spending, which is likely to result in fewer orders from the major customers of the German arms industry. The consequences of the changing circumstances could include: a reduction in production levels, redundancies, a loss of capabilities, and even the need to redirect output to the civilian market. The most acute effect of this will be on those companies that produce heavy equipment for ground troops (due to the changing needs of armed forces in Western Europe) and warships for the navy. Aviation and aerospace companies, such as Airbus Group (including its German subsidiary), have a greater capacity to combine military and civilian production. As a result, the German arms industry and the German government are working on ‘exit strategies’ to the emerging crisis. Concrete measures in several areas have already been taken.

(1) German arms manufacturers seek to break into new markets and to increase their market share outside NATO and the EU. In recent years, the Federal Security Council[11] has approved arms exports to new markets, some of which are highly controversial politically. Those German companies which are expanding their activities outside the NATO and EU are being increasingly supported politically, financially and through training (Bundeswehr, Bundespolizei) by the federal government[12]. As noted earlier, since 2011, the value of German arms exports to the “third countries” has exceeded the value of exports to the EU and NATO markets. The Gulf Arab states – Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, the UAE and Oman – are of growing importance due to their large defence budgets. They are however controversial in the eyes of German public opinion because of their authoritarian and oppressive governments. For the past few years, the growing interest in this region among German arms manufacturers has been transformed into tangible results. These included the deliveries of self-propelled howitzers and battle tanks to Qatar (by KMW); Saudi Arabia’s interest in heavy equipment for ground troops (although this contract has since fallen through) and, currently, in submarines and patrol vessels (Lürssen); as well as the contract for the modernisation of the infrastructure of the Saudi and Qatari border control systems (by Airbus Defence and Space). Germany’s arms-producing companies are also interested in Southeast Asia, as evidenced by the recent contracts for the sale of battle tanks, infantry fighting vehicles and anti-aircraft systems to Indonesia (Rheinmetall Defence) and submarines to Singapore (TKMS). Furthermore, some German manufacturers have been shifting their attention to the African markets, including North Africa. Prior to the Arab Spring, German firms signed two large contracts for the supply of frigates and armoured personnel carriers to Angola (TKMS and Rheinmetall Defence); there were also talks about the sale of submarines to Egypt (TKMS) but political instability in this country led to talks being suspended. According to government data, over the past few years Russia has not been a significant destination market for German armament and military equipment – with exports worth just 14-40 million euros a year. The value of German exports to Russia increased in 2011 to about 144 million euros (no figures are available for 2012) due to one large transaction – the sale of technologies to a combat training centre for Russian Armed Forces (Rheinmetall Defence). Nonetheless, Russia until the Ukraine crisis began was seen as a potential market for German arms exports – talks on future projects were held by the German and Russian defence ministries and arms manufacturers; recent contracts have focused mainly on ground troops. Germany has stressed that for political reasons it would only sell “defence” systems to Russia: training, logistics, supply and medical services. In 2012-2013 Russia tested the German armoured personnel carrier Boxer; it seems however that a deal – or future collaboration in this area – is unlikely.

Arms exports to “third countries” are regulated by federal government policies on the export of armament and military equipment. Such contracts can de jure only be approved in exceptional cases if the circumstances and Germany’s foreign and defence policy interests permit it. De facto, the definition of such circumstances leaves the decision to the discretion of the Federal Security Council. The defence lobby (BDSV) is satisfied with the current legal arrangement and has only called for faster licencing procedures. In Germany there has been a debate on arms export for a while now. Some German politicians (from the CDU/CSU and the FDP) have been arguing about the legal possibilities for simplifying the exports. Others (from the SPD and the Greens) have called for more restraint and greater parliamentary oversight. The current CDU/CSU-SPD coalition agreed that the Bundestag must be informed about each new licence issued by the Federal Security Council (however, this does not apply to preliminary enquiries) and the government is obliged to present two reports a year on the export of German arms. Only time will tell to what extent the SPD will try to use its time in government to change the recent trend towards a de facto relaxation of the country’s arms export policy. It would seem however that due to the increasingly difficult position of the arms industry and the high activity of its lobby, the federal government’s support for the arms producers will be bolstered. It is worth examining the proposals of the BDSV because it is possible that over time they will be implemented – although the government might not wish to highlight this fact publicly. The BDSV is calling for an interdepartmental strategy that would support the arms industry through economic, foreign and defence policies. The group also wants: a new interdepartmental agency focused on supporting export, an institutionalisation of the training support offered by the Bundeswehr to the customers of German defence products, and also faster licensing procedures.

(2) Secondly, German arms companies believe that a partial solution to their problems lies in mergers and joint ventures with local and international companies since these would allow them to enter new markets and expand the range of products they offer. By doing so they would be able to increase their global competitive advantage. One example of this approach is Rheinmetall International Engineering, a 50:50 joint venture established in October 2013 between Rheinmetall AG and Germany’s Ferrostaal. The JV brings together Rheinmetall Defence and Ferrostaal Industrieanlagen GmbH – the latter company operates in the oil and gas sector, mainly in the Middle East and North Africa. The JV aims to seek new markets also in Asia and in South America. In spring 2013, there were reports suggesting that Krauss-Maffei Wegmann was considering a merger with the French arms manufacturer Nexter, if the latter is privatised. In 2012, the European EADS group (currently Airbus Group) pursued a merger with Britain’s BAE Systems. It was hoped that the merger would improve BAE Systems’ access to European markets while EADS would benefit from the US and Middle East contacts of the British company. The merger fell through mainly due to objections from the German government. Berlin argued that the merger would marginalise German manufacturers and could threaten the position of the largest German developers of land systems (Rheinmetall and Krauss-Maffei Wegmann) by allowing BAE Systems easier access to European markets. Since it was forced to abandon the merger with BAE Systems, EADS (currently Airbus Group) has increasingly focused on the civilian market, which now accounts for the bulk of its income. It has also announced redundancies in the subsidiaries that supply the military sector (also in Germany). It is possible that Airbus Group will attempt to strengthen its position through a merger or asset acquisition in the future[13].

(3) Thirdly, the German arms industry is calling for better conditions for business within the EU and NATO. They are particularly interested in greater transparency in the implementation of the European Union’s Defence Package[14]; the standardisation of testing, certification and approval procedures; the harmonisation of defence procurement between EU member states[15]; and the abolition of offsets. Furthermore, it seems that the German “enable and enhance” initiative within the CSDP also has a business dimension in addition to its political dimension. It aims to support regional partners and enhance regional security (mainly in Africa) through training and the transfer of armament and military equipment. Similarly, a business element is visible in some of the German initiatives submitted to NATO, such as the Framework Nations Concept. This initiative seeks to consolidate national arms industries in clusters led by “framework nations”. These nations would retain a broad spectrum of capabilities that could be used in EU or NATO operations and they would also retain their arms manufacturing capacity at the expense of smaller partners joining a particular cluster. German analysts have suggested that under the Framework Nations Concept, Germany’s arms industry would play an important role across Central, and party also Northern, Europe. According to some experts, local countries could be given surplus armament and military equipment by the Bundeswehr (Eurofighters, NH90 helicopters and A400M transport aircraft), while logistics, maintenance and repair, and upgrading facilities would be located in Germany.

Appendices

German arms exports (Kriegswaffen) in 1997-2012[16]

|

Arms exports (Kriegswaffen)[17] |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

2009 |

2008 |

2007 |

2006 |

2005 |

|

Value of arms exports (billion euro) [incl. Bundeswehr sales]

- to NATO, EU and equivalent countries - to third countries |

0.946 [0.003] |

1.285 [0.038]

|

2.119 [0.043]

|

1.338 [0.131]

|

1.427 [0.135]

|

1.510 [0.033]

|

1.374 n/a

|

1.629 [0.087] |

|

41% 59% |

32% 68% |

77% 23% |

76% 24% |

65% 35% |

69% 31% |

n/a n/a |

64.2% 35.8% |

|

|

Share of arms exports in Germany’s total exports |

0.09% |

0.12% |

0.22% |

0.17% |

0.14% |

0.16% |

0.15% |

0.26% |

|

Value of export licences for arms and other equipment (Kriegswaffen und Ausrüstungsgüter)[18] |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

2009 |

2008 |

2007 |

2006 |

2005 |

|

Individual export licences (billion euro)

- NATO, EU and equivalent countries - third countries |

4.704 |

5.414 |

4.754

|

5.043

|

5.788

|

3.668

|

4.189

|

4.215

|

|

45% 55% |

57% 43% |

71% 29% |

51% 49% |

45% 55% |

66% 34% |

72% 28% |

61% 39% |

|

|

Collective export licences (billion euro) |

4.17 |

5.381 |

0.737 |

1.996 |

2.546 |

5.053 |

3.496 |

2.032 |

|

Destinations of German arms exports – Ranked by value |

2012 Value (million euro) |

2011 Value (million euro) |

2010 Value (million euro) |

2009 Value (million euro)

|

|

1. |

South Korea 262.499 |

Brunei 304.052 |

Portugal 812.111 |

Austria 500.396 |

|

2. |

Iraq 125.603 |

Singapore 210.772 |

Greece 403.487 |

South Korea 116.078 |

|

3. |

Poland 79.749 |

Iraq 159.465 |

Singapore 169.532 |

Netherlands 103.192 |

|

4. |

Italy 58.443 |

South Korea 75.290 |

Spain 76.547 |

Belgium 68.711 |

|

5. |

Singapore 58.114 |

Turkey 66.989 |

Belgium 66.511 |

Spain 50.900 |

|

6. |

USA 47.434 |

Brazil 49.262 |

Pakistan 64.952 |

Pakistan 45.538 |

|

7. |

Spain 43.005 |

UK 47.762 |

UK 52.820 |

UAE 43.252 |

|

8. |

Norway 35.171 |

Poland 42.361 |

Brazil 38.548 |

Greece 42. 821 |

|

9. |

UK 33.307 |

Canada 40.598 |

South Korea 37.079 |

Italy 38.461 |

|

10. |

Ghana 33.307 |

UAE 33.758 |

UAE 36.285 |

UK 35.009 |

[1] The Federation of German Security and Defence Industries (BDSV) is the most important source of general information on the topic. The BDSV was established in 2009 to lobby the government, parliament, public opinion and the media on behalf of its members. The group has about 50 members, mainly small and medium sized companies. Another important lobby (which pre-dates the BDSV) is the German Aerospace Industries Association (BDLI). The BDLI brings together about 200 firms, including many that also supply the arms industry, and other industry groups whose members cooperate with the defence sector. A number of niche companies, whose output is directed at the defence sector, also have affiliations with other trade associations.

[2] SIPRI, The SIPRI Top 100 arms-producing and military services companies in the world, 2012, http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/production/Top100

[3] Prior to restructuring, that is before 1 January 2014, the group was known as EADS; its subsidiaries based in Germany were Cassidian, Eurocopter, Astrium and Airbus Operations.

[4] Konzept zur Mittelstandspolitik – Rahmenbedingungen aus Sicht der Sicherheits- und Verteidigungswirtschaft, March 2013, http://www.bdsv.eu/de/Taetigkeitsfelder/Themen/Mittelstand.htm

[5] Andreas Seifert, Transformation der Bundeswehr: Transformation der Rüstungsbranche?, 11 June 2013, http://www.imi-online.de/2013/06/11/transformation-der-bundeswehr-transformation-der-rustungsbranche/

[6] Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand.

[7] Rheinmetall Defence is working with Israel’s IAI in the manufacture and servicing of Heron 1 UAVs, leased by the Bundeswehr; Diehl Defence has many foreign partners with whom it cooperates in the production of missiles: IRIS-T (with companies in Greece, Italy, Norway, Sweden and Spain), RBS15 Mk3 (with Sweden’s SAAB Dynamics), Spike LR (with Israel’s Rafael), and the AIM-9L Sidewinder (with the US Raytheon).

[8] In 2007, the capabilities (1) in the generation of complete systems included: satellite reconnaissance, combat aircraft, transport aircraft, helicopters, unmanned aerial vehicles, air defence systems, wheeled armoured vehicles, tracked vehicles, future infantry soldier technology (FIST), submarines and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), surface warfare vessels, mine countermeasures vessels, model building and simulations, IT systems for the Bundeswehr; and (2) regarding subsystems: electronic reconnaissance and electronic combat, countermeasures against WMD, countermeasures against anti-personnel landmines, artillery and improvised explosive devices. Bundesverteidigungsministerium and BDI, Gemeinsame Erklärung zu Nationalen Wehrtechnischen Kernfähigkeiten, 20 November 2007, http://www.bdsv.eu/de/Taetigkeitsfelder/Themen/Technologien.htm

[9] Despite objections from the SPD to the purchase of armed UAVs, the coalition agreement of the CDU/CSU-SPD government does not rule out that the UAVs will be purchased, but it is expected that the government would attach a series of conditions to any such contract.

[10] Bearing in mind that we are likely to see a rise in the value of production directed at the civilian security sector.

[11] The Federal Security Council is a federal government committee consisting of the Chancellor, the ministers of foreign affairs, defence, finance, home affairs, justice, as well as the minister of economic and development cooperation. The council approves large export contracts for German arms manufacturers, particularly in the case of customers from outside the EU and NATO.

[12] This last point warrants further analysis. The German ministries (of defence and internal affairs) have offered third states, customers of German arms manufacturers, training courses conducted by the Bundeswehr (this is the case with Rheinmetall Defence, which supplies technologies to a combat training centre in Russia) or by the Bundespolizei (as is the case with Cassidian, which has been involved in modernising the infrastructure of the Saudi border service). It was meant to make the purchase of German armament and military equipment, used also by the Bundeswehr and the Bundespolizei, more attractive.

[13] Following the failed merger, the national stakes in EADS (currently Airbus Group) held by France and Germany were cut back to 12% each.

[14] The Defence Package consists of two Directives: 2009/43/EC - abolishing barriers to the transfer of defence products within the EU, and 2009/81/EC - coordinating national procurement procedures regarding products, services and defence-related construction projects.

[15] Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie e.V., Grundsatzpapier. Sicherheit für das Industrieland Deutschland, June 2013, http://www.bdi.eu/download_content/SicherheitUndVerteidigung/32782_BDI_Sicherheit_5.pdf, p. 18.

[16] Source: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie, Rüstungsexportbericht 2005–2012.

[17] Ibid.

[18] The reports specify the value of the licences issued last year for the export both of arms (Kriegswaffen) and equipment (Ausrüstungsgüter). The value of the licences usually represents double the value of the actual arms exports (Kriegswaffen). It should be noted that licences are valid for several years and the contracts covered by the licences do not always lead to exports.