The Kharkiv oblast: a fragile stability

Kharkiv oblast, which is located in the immediate vicinity of the Donbas region, and which shares a 315-km stretch of Ukraine’s border with Russia, was one of the regions where attempts were made to kindle separatist sentiments during the spring of last year. Some central government buildings were briefly occupied by pro-Russian demonstrators who declared a ‘Kharkov People’s Republic’, but efficient countermeasures by the Ukrainian institutions of force quickly calmed the situation in the region. However, the oblast still remains a target for acts of sabotage, which are probably directed by Russian secret services. Nevertheless, the situation in the region is now stable, both in terms of public sentiment and local politics. The main competitors in the arena of local politics are Hennadiy Kernes, the mayor of Kharkiv, and Arsen Avakov, the current head of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry. Despite many years of hostility, neither of the politicians appears to have initiated a power struggle as yet – Kernes retains his influence on the city council, and Avakov controls the local security services.

The outbreak of the Donbas conflict was of key importance for the situation in the oblast, as it motivated the local elites – who feared a repeat of the separatist scenario in their region – to counteract the threat. The war’s impact on the situation in the region is clearly apparent. Kharkiv oblast has become the destination for many of the refugees escaping from the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. According to official data, they currently number around 170,000 people, but even the local authorities emphasise that the true figure actually exceeds 300,000.

At the same time, the Ukrainian-Russian conflict has adversely affected the economy of the region, whose business has so far largely been conducted with the Russian Federation. As a result, during 2014 there was a significant drop in the value of exports (by 8.3%) and imports (19.3%); the oblast’s industrial output has also fallen (by 5.2%). However, these figures are much better than those from other regions of Ukraine. The reasons for this include an increase in government orders from local defence industry plants. This has also led to many jobs being retained, which has helped to calm the public mood. The peace in the Kharkiv oblast remains fragile, however, and the threat to the region’s stability is high.

A divided society

Kharkiv oblast is the fourth largest region of Ukraine; it has a population of 2.73 million people, more than half of whom (1.4 million) live in Kharkiv city. An important component of the local patriotism is the fact that Kharkiv was the capital of Ukraine for 14 years[1]. To this day, the local people still cherish the uniqueness of their city and region in the country. In a study conducted in March by the International Republican Institute, up to 90% of the residents of Kharkiv declared their pride in their city, the highest such figure in the whole country. The capital of the district is also an important industrial, cultural and academic centre; the city has around 150 research institutes and more than 20 universities, and the number of students exceeds 200,000.

While the adjacent Donbas oblast was settled in the nineteenth century by workers from throughout the Russian Empire, the beginnings of the Kharkiv region’s development date back to the seventeenth century and the period of colonisation by the Cossacks[2]. Since then, the language and culture of Ukraine have clearly predominated in the region. Kharkiv only became dominated by the Russian language through the process of industrialisation in the nineteenth century and the Soviet period, and the ensuing influx of workers from Russia; according to data from the last Ukrainian census of 2001, 65.9% of Kharkiv city’s residents declared Russian to be their language of everyday communication. However, in the rest of the oblast, Ukrainian retains a clear advantage to this day; in most areas it is the mother tongue of 70-90% of the population.[3]

Due to the proximity of Russia and the number of its socio-economic links with the region, the Kharkiv oblast has for years been susceptible to Russian influence. Its information space is dominated by the Russian media, as a result of which the Kharkiv oblast has been exposed to the strong influence of Kremlin propaganda. This situation persists to this day; according to research conducted in late February by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, at the national level Russian media has had its greatest impact on the residents of the Kharkiv oblast, and has a considerable influence on shaping the political views of the local population[4]. As a result, the region remains second only to the Donbas as the most pro-Russian oblast in Ukraine, although it is clear that as a result of Russian aggression, the number of people supporting closer ties with Russia is falling, and the number of people who favour adopting a neutral position is rising.

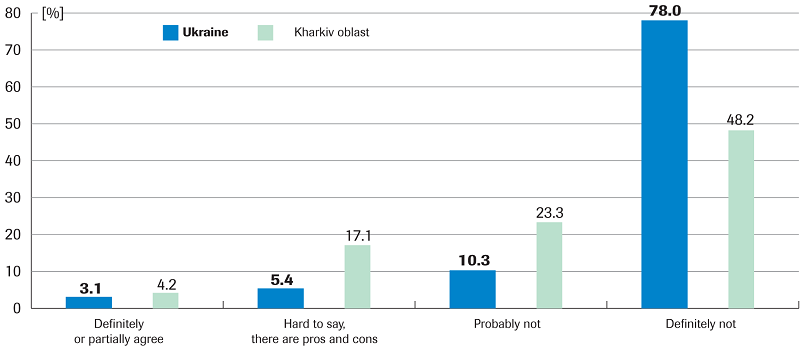

As recently as July 2014, Kharkiv oblast expressed the strongest support (after the Donbas) for Ukraine’s accession to the Customs Union (42%) and had the lowest percentages of supporters of European integration (31%) and entry into NATO (11%)[5]. Based on the latest surveys conducted by IRI in March this year, the number of people favourable to the European Union has remained at a similar level (30%), but there has been a definite fall in supporters of the Customs Union (to 22%). At the same time, the largest increase has been recorded in the number of undecided respondents who do not favour either the EU or the CU; 17% of respondents supported ‘another path of integration for Ukraine’, and 32% could not make an unequivocal decision. However, previous polls (conducted last December by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology) show that Kharkiv oblast still contains the largest group of people (in Ukraine) who do not rule out the possibility of the region joining the Russian Federation, and who thus support a possible separatist movement in the region; those who have a positive or ambivalent attitude to integration with Russia account for over 20% of the region’s inhabitants[6], although the number of people who declare a strongly pro-Russian attitude has fallen significantly.

The March survey by the International Republican Institute shows that the region is dominated by pessimism; as many as 72% of the region’s respondents declared that in their opinion the situation in the country is systematically worsening. They primarily blame politicians associated with the current government for this; low marks are given to the work of the president (62% of respondents), the government (70%) and parliament (70%). Only 26% of the respondents in the region trust the President (60% of respondents declare no confidence in him), and 16% the Prime Minister (with 69% giving negative responses). However, this drop in support for the government in Kyiv does not mean a rise in pro-Russian sentiment. The conflict in Donbas is an important factor influencing the views and moods in the region; anti-war sentiment in the region is rising steadily, and the oblast’s residents are aware that a possible outbreak of separatist sentiment could lead to a repeat of the events in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

Around a third of the population display clearly pro-Ukrainian sentiments, and their presence is by far the most visible in the region. This is because, with the acceptance of the central government, pro-Ukrainian movements have begun large-scale social activities, which has led to their current dominance of the public space. Thanks to the assent of the central government and the passivity of law enforcement agencies, Kharkiv has seen the removal of many Communist monuments, including the largest, a statue of Lenin which had stood in the central square of Kharkiv city. This change of mood has also led to the city being decorated with Ukrainian symbolism; for example, one of the multi-storey apartment blocks has been painted with the largest mural of Taras Shevchenko in Ukraine. Previously, the largest such mural in the city had been a portrait of Yuri Gagarin.

The influx of refugees from the Donbas has also been of great importance for the public mood in the region; the majority of the people who have fled the occupied territories have come to the Kharkiv oblast. According to official estimates, there are around 170,000 refugees in the region at the moment[7], but even the authorities acknowledge that the actual number is higher, over 300,000[8]; the offices have only registered those individuals who have asked for help, and many refugees have avoided official registration. Given that the Kharkiv oblast has around 2.7 million inhabitants, it means that the number of people residing in the region has increased by over 10% since the start of the conflict in the east. The rapid influx of refugees has contributed to a significant rise in the costs of housing (both rental and purchase), and has also affected the local labour market. It should be noted that a large number of the displaced persons do not conceal their distaste for the authorities in Kyiv.

The key players in the region

The most powerful players on Kharkiv’s political scene remain Arsen Avakov, the current head of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry, who comes from Kharkiv; and the current mayor Hennadiy Kernes, who has links to the former Party of Regions, and who enjoys great popularity in the city[9]. Since the local elections in 2010, the open conflict between the two politicians has been ongoing. At that time – in a very dubious manner – Kernes won the mayoralty, winning by just 0.63% (2726 votes) from Avakov, his main competitor[10]. After politicians associated with the Party of Regions took power in the city and the oblast, they struck hard at companies owned by Avakov, who had built up a substantial business empire over several years of activity in the region[11]. In January 2012 an investigation was initiated against the oblast’s former governor (between 2005 and 2010 Avakov was head of the Regional State Administration, appointed by Viktor Yushchenko), as a result of which he was forced to flee abroad[12]. He returned to the country in December that year, when he won a seat in parliament, and thus gained immunity from prosecution. The success of the revolution opened up an opportunity for Avakov to rebuild his influence in the city; in addition, his importance in the region rose thanks to his decisive intervention to prevent the development of separatist movements in the city in March and April 2014.

While Avakov has for some years adopted a strongly pro-Ukrainian position, Hennadiy Kernes’s policy is to keep open his options for making deals with anyone. He has made himself into a politician who is first and foremost a good steward of the city, a local patriot who respects the traditions and history of Kharkiv – hence, among others, his opposition to the demonstrators who wanted to pull down the Lenin statue in October last year, and his opposition to the possibility that Kharkiv City Council would officially name Russia as an aggressor state[13]. Although he has declared that he sees the future of Kharkov in Ukraine alone, he is clearly counting on a deterioration of the economic situation in the country. His political supporters are politicians associated with the Party of Regions, whose hopes for a successful political and business future are associated with an increase in dissatisfaction with the rule of the new Ukrainian government in the south-eastern regions of the country.

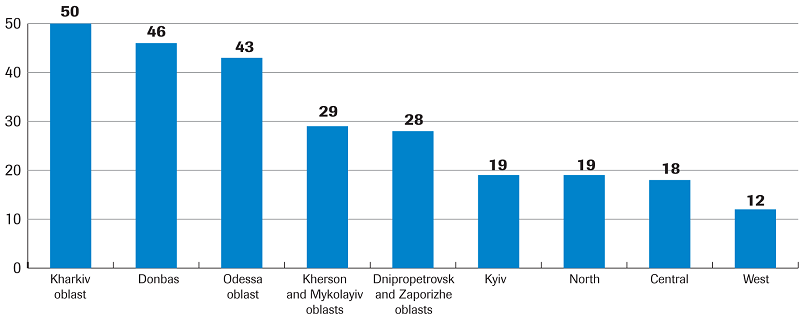

Both Kernes and his longtime business & political partner Mykhailo Dobkin (a current parliamentary deputy for the Opposition Bloc, who was that party’s candidate in the last presidential election) have retained their influence on both the City and Regional Councils, and many of their people are also still carrying out their functions in the regions of the oblast. Moreover, the last parliamentary elections showed that the popularity of former Party of Regions politicians in the oblast remains high; the Opposition Bloc scored a decisive victory in the region; and in the single-mandate constituencies[14], candidates with pasts in the Party of Regions won 13 of the 14 seats[15].

A chance to weaken the position of the Kernes/Dobkin team may arise in the forthcoming local elections (planned for this autumn), but the pro-Ukrainian parties’ failure to consolidate may pose a problem (their failure to agree on common candidates largely contributed to the success of the ‘Regionals’ in the parliamentary elections). At the same time, even Kyiv’s representatives acknowledge that Kernes still has considerable public support, and even if the local elections go to a second round, he remains favourite in the race for mayor. The pro-Ukrainian parties still lack a clear leader, and there is no strong, obvious rival to run against Kernes. Although there are rumours that Avakov himself could stand in the race, it seems that such a scenario is unlikely as long as he remains on the Council. However, Avakov’s final decision may depend on changes in the composition of the government (by resignation, for example) which could occur as a result of falling support for the main coalition party, the Popular Front, and rising tension within the coalition. At the same time, there is no-one else close to the head of the Interior Ministry who could successfully fight for the mayoralty[16].

Although Kernes has stated that he will participate in the upcoming local elections, he has still not decided which party he will run for; he may attempt to create his own local political movement. Meanwhile the General Prosecutor’s Office has initiated an investigation into the current mayor of Kharkiv, as a result of which an indictment has been forwarded to the court[17]; this could be a step by the authorities towards blocking his candidacy. However, such a firm action by the law enforcement agencies may result in a violent reaction from the mayor, who in the defence of his interests could mobilise his electorate and the administrative apparatus under his control, which could contribute to a destabilisation of the situation in the city.

Beside the Avakov/Dobkin and Kernes camps, there are no other strong political groups In the Kharkiv oblast; the Communists, who hitherto had been highly rated in the region, have seen a significant weakening of their support. The regional governor Ihor Raynin has been trying to create his own regional policy since his appointment; he is associated with Borys Lozhkin, the current head of the presidential administration[18].

Russian attempts at sabotage

Another factor influencing the situation in the region is the terrorist attacks which have been carried out by subversive groups controlled by Russia. According to the Ukrainian security services around 10 sabotage groups are operating within the oblast, under the control of Russian special services[19]; apart from these, there are also several ‘sleeper’ groups. Most of the saboteurs are Ukrainians (often with criminal records), but these groups also include citizens of the Russian Federation. Individual groups receive training in different Russian cities, primarily in Rostov-on-Don, Tambov and Belgorod (located only 70 km from Kharkiv), which also hosts the coordinating centre of the entire network. Depending on the type of attack, saboteurs are allegedly paid amounts ranging from US$300 to US$10,000. This information is based largely on testimonies from persons suspected of planning sabotage who have been detained by the Ukrainian security services; since last spring dozens of people involved in destabilising the situation in the region have been arrested[20].

According to government estimates, since the beginning of the year sabotage groups have carried out 12 terrorist acts in Kharkiv oblast; since the spring of last year, there have been a total of 48 such incidents[21]. The worst such act took place on 22 February this year, when during a march commemorating the tragic events on the Maidan in Kyiv, an explosive device hidden in snow by the roadside went off. Four people, including a 15-year-old boy, were killed as a result of the explosion, and nine were wounded.

The saboteurs’ most common means of attack is planting concealed explosives. Their main targets are railway and military facilities, as well as the local offices of pro-Ukrainian organisations dealing with soldiers who have been on the front line, among others. Apart from isolated incidents, no-one has been injured, and the material losses inflicted by the saboteurs have also been minimal, which calls the effectiveness of their actions into question. Because these acts of sabotage in Kharkiv oblast have been relatively harmless, they should be seen primarily in a political light. They are a signal from Russia that forces still exist within the region which are able to oppose the Ukrainian authorities; and they are also aimed at creating the impression that a ‘Kharkov People’s Republic’ scenario is still possible. In addition, as similar terrorist acts are taking place in other towns in south-eastern Ukraine (mainly Odessa), Russia’s subversive activity should be seen as another tool to destabilise the situation in the country.

It is difficult to assess the impact of these actions on the public mood in the oblast. Due to the increased activity of the authorities and the Security Service of Ukraine, the majority of the threats have been counteracted; the effectiveness of the Security Service’s actions is important for public confidence in the central government. At the same time, the media atmosphere around this activity means that some of these incidents have been exaggerated by both the government and the Ukrainian media, which may distort the real image of the situation. However, there is no doubt that the terrorists’ main aim is to maintain the level of unrest in the region, so that in the future it could lead to a possible revival of anti-Kyiv sentiments. Any failure by the security services in the field of counter-terrorism could in fact undermine the central government’s power and contribute to the growth of discontent with Kyiv in the region.

The region’s economy in the face of the crisis

Kharkiv oblast, which is one of the most important regions for the Ukrainian economy (in 2013, it generated 5.6% of total Ukrainian GDP), has been severely affected by the nationwide economic crisis. As a result of the unstable situation in the country, and because of the proximity of the area affected by the war, there has been a sharp decline in imports and exports from Kharkiv oblast, which has led to a systematic deterioration in the situation. While in 2014 the value of exports amounted to US$1.82 billion (down 8.3%) and imports to US$1.88 billion (down 19.3%), in the first quarter of this year, these values fell to US$273 million (down 41% compared to the same period in the previous year) and US$283 million (down 39.8%) respectively. Meanwhile last year, Ukraine’s overall exports fell by 13.5%, and its imports by 28.3%.

Despite these problems, the oblast remains an important industrial centre for Ukraine; there are over 600 factories on its territory, of which around 70 are state-owned. Local production is based primarily on machine factories (including agricultural products and elements for nuclear power plants), chemicals and metalworking. A strong role in the regional economy is also played by factories related to the energy sector, armaments and food. Thus, production in the region is highly diversified, and primarily based on mechanical production, which distinguishes it from the economy of the neighbouring Donbas, focused on heavy industry (metallurgy) and mining (mainly coal). Another difference is that the Kharkiv region does not contain so many developed oligarchic groups, who took control of entire branches of the economy in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

In 2014, the industrial production value in Kharkiv oblast fell by 5.2% (the overall decline in production in Ukraine ran at the level of 10.1%), and amounted to US$4.6 billion (in January-March this year the figure stood at about US$940 million, a decrease of 14.1% compared to the same period in the previous year), which accounted for 6.1% of national production in Ukraine last year.

The region’s economic situation has to a certain extent been rescued by an increase in orders by the state from the defence industry companies based in the oblast (Ukroboronprom has 12 plants in the oblast), allowing it to maintain a high level of employment in some of the plants. However, even in this area some companies have been having problems; salaries in the Kharkiv State Aviation Production Plant have not been paid since last August due to financial problems.

Small and medium businesses, which have largely developed in the oblast due to its proximity to the Russian border, have suffered particularly because of the conflict with Russia. Difficulties in border traffic, including tighter border controls, have caused significant problems in doing business. The international situation has also affected the industrial plants located in the region; the vast majority of their production was oriented towards exports to Russia, which in recent years accounted for around 47% of the region’s exports. It is true that the regional authorities have ensured that many of the plants managed to change the markets for their sales, but it must be borne in mind that most Ukrainian industry produces goods that are either not competitive in terms of quality and price, or for which demand exists only on specific markets. As a result, many factories have had to reduce production.

Conclusions

As a result of the consensus of local elites and the decisive action taken by Kyiv to discipline local power structures, separatist sentiments in the region have been successfully dampened down. However, the sabotage groups in the region, which the Security Service of Ukraine is actively trying to counteract, remains an unresolved problem.

The failure of the ‘Kharkov People’s Republic’ project stems not only from the government’s positive and active fight against the separatist groups, but also from the fundamental differences between the Kharkiv and Donbas oblasts. The former – in contrast to the neighbouring Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts – has much stronger Ukrainian roots. Although in Kharkiv city most residents speak Russian, the rest of the oblast speaks Ukrainian on a daily basis. The machine-based industry in the region means that educated engineers are indispensable in the production process; as a result many universities have been established there, and Kharkiv itself is an important Ukrainian academic centre. On a national scale – also due to the large number of art schools – Kharkiv is a centre of Ukrainian culture. As a result, the region has a sufficiently large number of active, pro-Ukrainian-minded people, who have been able to resist separatist tendencies.

In recent months, Kharkiv oblast has seen the marginalisation of people and organisations of a pro-Russian political orientation. This does not mean, however, that such people do not exist. The oblast remains the most susceptible region of Ukraine (apart from the Donbas) to Russian propaganda, and because of its economic ties with the Russian Federation, it suffers the consequences of the Ukrainian-Russian conflict. The deteriorating economic situation of the country and the region, together with the rising prices and the increases in rates for municipal services, could contribute to a rise in discontent among some of the oblast’s population, which both politicians opposed to the current government in Kyiv (mainly the current members of the Opposition Bloc and former members of the Party of Regions) as well as Russia will want to exploit. The issue of the 300,000 refugees from the Donbas, and their future in the region, is another growing problem.

The most important factor which could destabilise the situation in the region, however, may be the upcoming local elections; if the government in Kyiv decides to prevent Hennadiy Kernes from running for mayor of Kharkiv (by bringing a conviction in the criminal trial against him), this may cause a violent reaction from his supporters, and contribute to the destabilisation of the situation in the entire region. In addition, it remains possible that the forthcoming elections will witness a political struggle for power between Kernes and Arsen Avakov, the current head of the Interior Ministry. For now, however, Kharkiv oblast maintains its fragile peace, and all the parties are waiting for the next developments in the economic situation and on the Donbas front.

Appendices

Do you agree that your region should secede from Ukraine and join the Russian Federation?

Source: responses to opinion polls conducted by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology on 6-17 December 2014

Number of parliamentary seats in single-mandate constituencies won by politicians linked to the Party of Regions (parliamentary elections in Ukraine in 2014)

Index of the influence of Russian media on the views of the inhabitants of Ukrainian regions

Source: opinion polls conducted by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology on 14-24 February 2015

[1] In 1920-1934 Kharkiv served as the capital city of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

[2] The Kharkiv oblast, together with the Sumy oblast, lie within the historical areas known as Sloboda Ukraina or the Slobozhanschyna; during the mid-eighteenth century this was a Cossack autonomous region, first as part of the Russian tsar’s dominions, and then the Russian Empire. In 1765, on the orders of Catherine II, the autonomous region was abolished and the land taken over by the Russian administration as the Sloboda Ukraine Governorate.

[3] Data from the Ukrainian national census of 2001, http://ukrcensus.gov.ua/

[4] See Appendix 3.

[5] According to a survey conducted between 28 June and 10 July 2014 by the Rating research group. See http://ratinggroup.com.ua/products/politic/data/entry/14098/

[6] See Appendix 1.

[7] According to estimates by the State Service for Emergency Situations: http://www.mns.gov.ua/news/34232.html

[8] http://www.sprotyv.info/ru/news/15855-gubernator-harkovskoy-oblasti-igor-raynin-situaciyu-na-harkovshchine-ne-stoit

[9] Kernes is viewed positively by 48% of the capital’s residents, 34% are dissatisfied. Data from the March research by the International Republican Institute.

[10] According to the exit polls Avakov won, with 34.7% of the votes, with Kernes receiving 30.9% in the polls. http://ru.tsn.ua/ukrayina/oficialno-kernes-pobedil-na-vyborah-mera-harkova.html

[11] Avakov controlled or remains in control, via his own appointees, shares in many branches of the local economy, including food, construction, gas, energy, media and banking.

[12] The case against him was brought by the Kharkiv prosecutor’s office after receiving reports of possible criminal activity by the Regional State Administration, which at that time was run by Mykhailo Dobkin. The cause of the prosecution was apparently the illegal alteration in the status of a 55-hectare allotment from agricultural to industrial use, which could have earned Avakov a 6-year prison sentence. After this affair came to light, Avakov escaped to Italy.

[13] Kernes has on two occasions emphasised in the media (in June 2014 and February 2015) that he does not see Russia as the aggressor, as it “has given loans and delivered gas to Ukraine”. He has also stated that it is necessary to precisely research and verify any reports of the presence of Russian forces in the Donbas.

[14] Parliamentary elections in Ukraine are held on a mixed basis; half of the deputies are chosen by proportional representation, and the other half in single-mandate constituencies,

[15] See Appendix 2.

[16] Possible candidates from within Avakov’s camp include his advisers Anton Herashchenko (currently a parliamentary deputy) and Ivan Verchenko (a leader of Kharkiv’s Euromaidan).

[17] On 26 March this year, the Prosecutor General's Office submitted to the court an indictment against Kernes and two of his bodyguards. All three are suspected of kidnapping, torturing and beating activists from the Kharkiv Euromaidan. In April, a court in Poltava started proceedings against the accused, but the hearing only began at the third attempt; Kernes claimed health issues, and there were also provocations which prevented the trial from starting. In the case of Kernes, a conviction would carry a sentence of 5 to 10 years in prison.

[18] From November 2014 until his appointment to the governorship, Raynin was first deputy head of the Presidential Administration under Lozhkin. Previously, Raynin had worked for many years in Kharkiv’s Regional State Administration.

[19] http://www.unian.net/society/1012408-v-harkove-deystvuet-10-razvedyivatelno-diversionnyih-grupp-hnr.html