Germany’s ‘refugee’ problem. The most important test for Chancellor Merkel and the grand coalition

Cooperation: Lidia Gibadło

The rapid increase in the number of immigrants from outside of the EU coming to Germany has become the paramount political issue. According to new estimates, the number of individuals expected arrive in Germany in 2015 and apply for asylum there is 800,000, which is nearly twice as many as estimated in earlier forecasts. Various administrative, financial and social problems related to the influx of migrants are becoming increasingly apparent. The problem of ‘refugees’ (in public debate, the terms ‘immigrants’, ‘refugees’, ‘illegal immigrants’, ‘economic immigrants’ have not been clearly defined and have often been used interchangeably) has been culminating for over a year. Despite this, it was being disregarded by Angela Merkel’s government which was preoccupied with debates on how to rescue Greece. It was only daily reports of cases of refugee centres being set on fire that convinced Chancellor Merkel to speak and to make immigration problem a priority issue (Chefsache). Neither the ruling coalition nor the opposition parties have a consistent idea of how Germany should react to the growing number of refugees. In this matter, divisions run across parties. Various solutions have been proposed, from liberalisation of laws on the right to stay in Germany to combating illegal immigration more effectively, which would be possible if asylum granting procedures were accelerated. The proposed solutions have not been properly thought through, instead they are reactive measures inspired by the results of opinion polls. This is why their assumptions are often contradictory. The situation is similar regarding the actions proposed by Chancellor Merkel which involve faster procedures to expel individuals with no right to stay in Germany and a plan to convince other EU states to accept ‘refugees’. None of these ideas is new – they were already present in the German internal debate.

Germany’s asylum and migration compromises

In Germany, the right to seek asylum is guaranteed in the constitution: “Persons persecuted on political grounds shall have the right of asylum”. For many years since 1949, this provision, contained in Article 16a of the Basic Law, was not precisely defined. A debate on amending the asylum law started as late as the mid-1980s. It was triggered by a rapid increase in the number of asylum applications and a surge in economic immigration. Changes to the policy towards foreigners were one of four issues requiring immediate regulation, mentioned by Chancellor Helmut Kohl in his policy statement delivered in 1982. Its main points involved stopping the uncontrolled influx of immigrants and eliminating the possibility of them abusing the asylum laws. The asylum campaign gained speed in 1986. Proponents of the plan to introduce limitations included CDU/CSU politicians, although no unified position on the scope of proposed changes was ever adopted by the party. The minister of labour warned against tightening the law. Employers’ unions were also opposed. Ultimately, Chancellor Kohl dropped the plan to introduce changes. The debate reignited in 1990 ahead of elections to the Bundestag. This time, the debate was heated and its participants included newspapers such as Bild and Welt am Sonntag, which supported the proposed changes. Opponents included the SPD, the Green Party, a faction of FDP, church organisations, human rights activists, trade unions, business and industrial associations. Ultimately, the growing number of anti-immigrant attacks convinced SPD to change its view, which made it possible to attain a parliamentary majority and change the law.

The decision entailed limitations of the possibility for granting the right to asylum in Germany. The most significant changes concerned:

1. The principle of safe third countries

Individuals arriving in Germany from countries categorised as safe third countries cannot apply for asylum. This group of countries includes Germany’s neighbours. If an individual is stopped at the border or near the border, they may be sent back immediately.

Article 16a of the Basic Law contains a definition of a safe third country and specific countries are listed in the law on asylum granting procedure (Asylverfahrensgesetz).

2. The principle of safe country of origin

If a specific individual comes from a safe country of origin, they cannot apply for asylum. Safe countries of origin are defined in a law which requires approval by the Bundesrat.

3. Regulations regarding airports

An entry which enables one to apply for asylum is possible only by air. Arriving in Germany via the territory of safe countries precludes someone from applying for asylum. If an individual comes from or has arrived from a country categorised as safe, accelerated airport transit zone procedures and limited luggage search will be actioned, so that they can be sent back immediately.

4. The law on benefits for asylum seekers

The law (Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz) was passed in 1993. It defines the form and the amount of benefits offered to asylum seekers who have been granted the right to tolerated stay in Germany and to foreigners obligated to leave the country.

5. The status of war refugees

One of the changes involved introduction of a separate status of ‘war refugees’ to allow individuals fleeing to Germany due to a war in their home country to skip the standard asylum seeking procedure. Ultimately, these individuals are granted the right to tolerated stay.

Another significant change which impacted asylum regulations was the adoption of the immigration law[1]. It came into force on 1 January 2005 and was preceded by a major debate. The beginning of the debate on the future of Germany as a destination country for immigrants can be traced to the signing of the coalition agreement between SPD and the Greens. This agreement announced changes intended to harmonise legislation with reality, which involved recognising the fact that Germany is a destination country (and society) for immigrants[2]. Implementation of the plans seemed certain. In January 2000, a new law on citizenship came into force which simplified the citizenship granting procedure (especially in the case of immigrants’ children). In October 2000, the daily Die Welt published an article by Friedrich Merz, the head of the CDU/CSU grouping at the Bundestag, in which he heavily criticised the assumptions of the red-green immigration policy and introduced the term Leitkultur (leading culture) to the German debate. Leitkultur was understood as a commonly accepted definition of “what we understand as our culture”[3]. Leitkultur stood in contrast to the model of a ‘multicultural society’ frequently referred to by politicians of SPD and the Greens. In subsequent debates, emphasis was placed not so much on what it meant to be German as on what immigrants should respect if they wanted to live in Germany. CDU’s leader Angela Merkel said: “We want recognition for our nation, our fatherland, open patriotism, tolerance and civil courage”. Cem Özdemir of the Green Party replied that this view means that the immigration policy should emphasise the need to assimilate the foreigners instead of integrating them. Conservative politicians pointed to the problem of ‘parallel societies’ (Parallelgesellschaften) which allegedly emerged as a result of integration policy being too liberal or non-existent. The terms Leitkultur and Parallelgesellschaft have entered the German political vocabulary. The 2001 WTC attacks cooled down the enthusiasm of SPD and the Greens for reforming immigration law. In 2000–2001, the parties worked on their own ideas for legislation to regulate immigration policy. In its proposal, SPD focused on immigration of highly qualified workers, FDP wanted the law to respond to the needs of the labour market, and CDU/CSU opted for limiting immigration and placed emphasis on the issues of security and protection of German identity. The Christian Democrats were not willing to agree to unrestricted immigration and expected it to be shaped in line with “national interests and national identity”. It also wanted this phrase to be included in the law’s provisions. Ultimately, a provision emphasising the need to make immigration dependent on “the feasibility of accepting and integrating immigrants” was included in the text. Contrary to the plans, which called for preparing “Europe’s most modern immigration law” which would de facto mean that Germany would become open to immigrants, a law was adopted which limited the scale of immigration.

The part of the law which concerned refugees contained a broadened scope of possibilities for granting refugee status: now an individual can be considered a refugee if they are persecuted by a political party, an organisation, a non-state actor in control of a state or a large portion of it and where the state is unwilling or unable to guarantee protection to such an individual. Gender-related persecution was also added to the list. New requirements pertaining to foreigners were introduced including the requirement to attend integration courses (this was the result of the debate regarding Leitkultur). Failure to participate in these courses would be grounds for reducing social benefits. Other changes concerned spouses of foreigners living in Germany. As of now, they can join their husband or wife if they are of age and have a basic command of German[4].

Statistics

The current public debate regarding ‘refugees’ seems to suggest that all those who are seeking asylum in Germany come from Syria and reached Germany having crossed the Mediterranean Sea by boat. The rapid increase in the number of asylum applications has largely been related to the events in the Middle East, especially the wars in Syria and in Iraq[5], but not exclusively. 42% of individuals who applied for asylum in Germany by 1 July 2015 came from the Western Balkan states and have no chances of being granted refugee status or another form of international protection or tolerated stay (for this group the proportion of positive asylum decisions is 0.2–0.4%). A large majority of immigrants from the Balkans are economic immigrants using the asylum system to enter the German job market. In their view, the prolonged procedure for processing applications is attractive, since during this period they can make use of the assistance offered by the German welfare system. This includes free shelter, food and pocket money (for personal expenditure). In the case of this group of immigrants, the procedure takes around five months. A rapid increase in the number of ‘refugees’ coming to Germany from Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro was observed in 2009-2010 and was related to visa abolition for citizens of these states[6].

In 2014, 202,834 asylum applications were submitted to the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). This was a 59.7% increase compared to the previous year. Until 1 July 2015, non-EU immigrants submitted 218,221 asylum applications. This means an increase of 125% compared to the corresponding period in the previous year. Most of these asylum applications were submitted by citizens of Syria (42,100), Kosovo (29,997), Albania (29,353), Serbia (11,642), Iraq (10,501), Afghanistan (10,191) and Macedonia (5,514). In early 2015, the German Ministry of the Interior estimated that 450,000 asylum applications would be submitted in 2015, which would be the highest number even recorded. So far, the highest number of asylum applications submitted was in 1992 – 438,191. In August 2015, the Interior Minster Thomas de Maizière expanded the initial estimates by another 350,000. Prime ministers of several German federal states have proposed their own estimates compiled on the basis of the dynamics of the influx of ‘refugees’. According to them, the expected number could be as high as one million.

Germany is Europe’s most popular destination in terms of submitted asylum applications (in absolute numbers). In 2014, Sweden – ranked second – registered 81,300 applications, Italy 64,600 and France 62,700. The situation looks different, though, when analysed in terms of the number of asylum seekers per 1,000 inhabitants. In this case, in 2014 Germany was ranked eighth (2.5 applications per 1,000 inhabitants) after Sweden (8.4), Hungary (4.3), Austria (3.3), Malta (3.2), Switzerland (2.9), Denmark (2.6) and Norway (2.6). In 2014, asylum, refugee status or another form of tolerated stay was granted to 31.5% of the applicants. By 1 July 2015, the ratio rose to 36.7% and 63.3% of the applications were rejected.

At the beginning of August 2015, around 755,000 individuals of different status who came to seek asylum were staying in Germany. These included:

- 38,600 asylum seekers to whom Germany guarantees protection pursuant to Article 16 of the constitution (Germany’s legislation on the matter – see Appendix 1);

- 145,000 individuals who were granted refugee status pursuant to the Geneva Refugee Convention and the European Convention on Human Rights;

- 50,000 individuals who cannot be considered ‘refugees’, but have been guaranteed the right to additional protection due to the fact that their life and health are threatened in their countries of origin;

- 62,600 individuals who have been granted the right to stay due to “international, humanitarian or political” reasons pursuant to the law on stay, paid work and integration of foreigners;

- 250,000 individuals who submitted their asylum applications and are waiting for them to be processed;

- 80,000 individuals whose asylum applications have been rejected but who are allowed to stay in Germany for important humanitarian, personal or social reasons pursuant to the law on stay, paid work and integration of foreigners;

- 129,000 individuals who are tolerated because they cannot be expelled (e.g. due to their illness or the lack of travel documents).

Additionally, according to data as of March 2015, 150,000 individuals who had been ordered to leave the country were remaining in Germany.

Official statistics do not include individuals who are staying in Germany illegally and have not applied for asylum, i.e. typical illegal (non-regulated) immigrants. According to estimates, their number could be between 100,000 and 400,000.

A survey conducted in 2014 by BAMF identified reasons why Germany is the most popular destination for ‘refugees’. These include:

- The legal system. In the opinion of ‘refugees’, Germany is a country which guarantees safe existence and care. The asylum procedure and the attitude of the police towards immigrants have also been praised. According to experts, liberal legislation and law enforcement practice make it possible for immigrants to stay in Germany for a longer time.

- The presence of diasporas (migration networks).

- Decisions taken by people smugglers. Sometimes the decision regarding destination country is not taken by migrants themselves, but by gangs of people smugglers. BAMF has discovered that Germany is the most popular destination proposed by criminals. This might be due to Germany’s geographical location and its relatively liberal law.

- Availability of education and healthcare.

- Favourable economic conditions and good prospects of finding employment.

The European Commission has identified several other ‘pull factors’: duration of the asylum procedure (the longer, the better), the amount of benefits, the opportunity to engage in begging or illegal work and the knowledge of asylum granting ratios.

Germany’s social and political polarisation

No other topic is currently causing greater division within society than immigration. According to a survey by GfK, for the first time in 22 years Germans have not pointed to unemployment as the country’s biggest challenge. The biggest problem that Germany has to face is immigration – this view was supported by 35% of the respondents. Another survey conducted in July 2015 revealed that 34% of Germans believe that their country should be accepting as many refugees as it did so far (a drop of 9 percentage points as compared to January 2015). 23% of the respondents said that Germany should be accepting more refugees; 38% – that the number of refugees accepted should be smaller (an increase of 17 percentage points). 93% of Germans believe that individuals fleeing war should be offered shelter in Germany. 80% of the respondents would accept refugees persecuted on grounds of their religion and nationality. 69% are against accepting individuals who come to Germany fleeing poverty and unemployment. Polarisation of society has been evident not only in opinion polls. This is confirmed by a rapid increase in the number of attacks on refugee centres: 31 centres were set on fire in the first half of 2015 (in the whole of 2014 there were 36 such attacks). 110 demonstrations at refugee centres and rallies against the establishment of new ones were organised (in 2014 there were 292 such demonstrations). At the same time, many Germans are involved in helping the refugees and attend demonstrations of support for refugees (see Appendix 2).

There is no consensus within individual parties as to how Germany should react to the growing number of refugees and divisions run across the parties. Representatives of CSU, a portion of CDU, and some prime ministers of federal states who represent SPD opt for acceleration of asylum procedures and a more effective fight against illegal immigration. The centrist faction of CDU and the moderate wing of SPD consider it necessary to pass a unified migration law which would guarantee an input of skilled workers to the German economy and would eliminate the opportunity for using the asylum system to enter the labour market at the same time. The left wing of SPD and the opposition Green Party demand a liberalisation of laws governing the right to stay in Germany. The divisions have been confirmed in opinion polls conducted among supporters of specific parties. A positive answer to the question as to whether Germany should take in all those who seek shelter was given by 31% of supporters of CDU/CSU, 34% SPD, 65% the Greens, 32% the Left and 9% AfD. The debate has become ideologised and dominated by vague terms to an extent which makes it impossible to come up with substantial arguments. When Joachim Gauck compared the ‘refugees’ to so-called expelled Germans from before 70 years ago, the leader of CSU Horst Seehofer expressed his outrage and said that one should not compare the expelled to “asylum swindlers”. His statement was heavily criticised by Claudia Roth (the Greens), who considered these words “almost disgusting”. In reply to this, in turn, Andreas Scheuer, CSU’s secretary general, advised her to use her brains more often. Yasmin Fahimi (SPD) accused CSU of fuelling anti-immigrant resentments.

The inefficient system

There are no estimates as to the upper limit of Germany’s potential for taking in ‘refugees’. In late August 2015, the interior minister announced that estimates suggesting that 800,000 asylum seekers may be expected this year should be treated as an emergency situation. The influx of immigrants has already caused or aggravated problems and conflicts and revealed deficiencies in several areas of the German state’s functioning.

The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) was granted approval to employ another one thousand workers in 2015. This is expected to help process the accumulating number of asylum applications, which has now reached 250,000. To employ and train office staff takes time, however. In this situation, local governments in some regions of Germany, including North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), called on retired administration workers to help as volunteers. 150 retired workers responded to the request by Hannelore Kraft, prime minister of NRW. Despite these problems, the Federal Ministry of the Interior has promised to overcome the backlog within six months. Four new centres will be established to process the applications. Moreover, there are too few facilities to offer shelter to refugees awaiting their asylum decision. Federal states and communes have been using temporarily adapted container homes, tents and former barracks, or even former supermarkets and ships for this purpose.

Providing shelter and food to refugees is the responsibility of communities which take them in. The related cost is reimbursed to the communities by federal states according to various schemes; local governments are increasingly having problems fulfilling this obligation (and the calculations must take account of the debt brake). In Bavaria, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Saarland the costs borne by local governments are reimbursed in full. In most other federal states, communities receive a yearly lump sum for each refugee. In Hesse the amount is EUR 6,251–7,554, in Lower Saxony EUR 6,195, and in Rheinland-Palatinate EUR 6,014. Depending on the federal state, the basic amounts earmarked for food and shelter can be supplemented by a lump sum for healthcare. Baden-Württemberg (BW) has applied its own mechanism: it offers EUR 13,260 per year per each ‘refugee’. What exactly this sum will be spent on depends on the specific community. The sum covers around three quarters of the yearly subsistence cost of one immigrant in BW. Additionally, aside from shelter, food and clothing, asylum seekers receive pocket money. For single persons it is EUR 143 per month, for couples – EUR 129 per month per person, and EUR 113 for each subsequent household member and EUR 85–92 for each child. In 2014, federal states spent EUR 2.2 bn on providing care to immigrants. For 2015, 16 federal states have earmarked EUR 6 bn in their budgets for this purpose. It might turn out, however, that this amount will be insufficient. Initial estimates regarding the number of ‘refugees’ were two times lower than the current ones. If the scenario revealed by the Interior Ministry proves true, German federal states will have to spend as much as EUR 10 bn. Federal states have emphasised the need for greater financial involvement from the central government. In 2015, federal states and communes are expected to receive additional funds from the central budget (at least EUR 1 bn) for providing help to ‘refugees’. In 2016, they will receive an additional EUR 3 bn for this purpose.

In March 2015, 150,000 individuals whose asylum applications had been rejected and who had been ordered to leave Germany were still staying in German territory. Expulsion procedures belong to the scope of responsibilities of federal states, these however are not particularly diligent in implementing them. This often results from political and ideological motives, especially in the case of the more left-oriented states (such as Bremen). Politicians do not want to act in contrast to what their voters expect. Supporters of left-wing parties believe that it is inhumane to expel immigrants.

Statistics and expert opinions suggest that a large portion of non-EU immigrants will permanently stay in Germany – regardless of the status of their asylum application. Opponents of the plan to expel ‘refugees’ claim that the German job market needs more than 500,000 new workers. In the context of non-EU immigrants who apply for asylum in Germany, this argument is false. The job market is able to absorb them only to a limited extent. This is due to a number of reasons. These individuals are not ‘available’ for the job market immediately, but after at least several months. Pursuant to a decision by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, a majority of such individuals are only granted the right to tolerated stay, which can be rescinded. This, in turn, discourages potential employers from employing ‘refugees’, because they can lose a member of their staff at any time. The situation is similar in the case of companies which could offer vocational training. Another important factor is competition. The debate on refugees often omits the fact that there are also individuals who emigrate legally to Germany. In the first half of 2014, over 667,000 individuals emigrated to Germany (in 2013 it was 1.2 million, with refugees accounting for a mere 16% of this number, i.e. 77,000). Refugees seem to be in a hopeless situation if they are to compete with legal immigrants, including due to bigger cultural differences and inadequate knowledge of the German reality. Although the German job market needs immigrants, it is the qualified, initially selected workers that are most wanted. Most refugees only have a chance of finding basic jobs which do not require specialist qualifications. These jobs are characterised by tough competition between legal and illegal immigrants. Therefore, there is a risk that the current refugees coming to Germany will become unemployed residents of immigrant ghettos[7].

Treating the symptoms

Activities carried out by Germany’s Interior Ministry have focused on two areas: relieving central and state administration and preventing a continued influx of ‘refugees’ or encouraging them to leave Germany on their own. On 1 August 2015, a principle started to apply according to which an immigrant whose asylum application is rejected twice will be banned from entering Germany for five years. On 21 August 2015, the interior minister Thomas de Maizière announced further solutions to discourage citizens of the Western Balkan states from coming to Germany. The new provisions would include a requirement according to which individuals whose asylum applications have little chance of being accepted would await their decisions in refugee centres organised by the central administration and would not be transferred to local centres run by communities. Currently, asylum seekers get assigned to communities after three months at the latest. Another restriction involves a reduction in the sums paid out in cash to asylum seekers waiting for their asylum application to be processed. Whenever possible, cash benefits are to be replaced with vouchers which can be exchanged for specific services, for example food. Proposals presented by Maizière were accepted at a meeting of coalition party representatives on 6 September 2015. Additionally, the coalition partners agreed that Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro should be included in the list of safe countries (this will be difficult to achieve, as the Greens are against it and their approval is necessary for the proposal to be approved by the Bundesrat). An additional 150,000 places in refugee centres will be created. To speed up the process of expelling ‘refugees’ from Germany, federal police will employ 3,000 new officers. The coalition has also agreed on a number of programmes to improve living conditions offered to ‘refugees’ and to support their integration. The government intends to support social housing initiatives and introduce measures to enable non-EU immigrants to take up temporary jobs. Regarding European issues, the Grand Coalition confirmed the position communicated earlier by Chancellor Merkel[8]. Additionally, a plan was announced to provide financial assistance to those EU countries which would be particularly affected by the presence of ‘refugees’ and greater involvement in the fight against people smugglers was declared. Vice Chancellor and SPD leader Sigmar Gabriel threatened those states of Eastern Europe which continue to refuse taking in refugees that border controls might be introduced and the rules of distributing EU funds might be changed[9]. Germany’s Foreign Ministry is to receive EUR 400 mn to carry out an information campaign in North Africa targeting potential emigrants. BAMF has already launched a social media campaign in Serbia and Albania to inform citizens of these countries that they would have no chance of a positive decision should they apply for asylum in Germany. Federal police produced a TV spot showing deportations from Germany.

Due to social and political polarisation, the actions carried out to prevent the influx of ‘refugees’ to Germany are likely to have a temporary effect only. They seem to disregard one basic cause of the current situation: the German asylum system which makes Germany the most popular destination for migrants. The divide within society and the political elite is leading to a situation in which contradictory messages are being communicated to external partners, which in turn provides encouragement for potential immigrants. An attempt to thoroughly reform the asylum system would trigger a debate similar to the one which took place in 1992, when the right to seek asylum in Germany was limited. That debate focused on questions concerning whether German society is a society composed of immigrants, whether immigration enriches or threatens the local culture, whether crimes committed by foreigners are a real problem, etc. All these questions are being continually debated in Germany, although they have not been placed at the forefront of public debate. If they were emphasised more in public debate, the social mood couldbecome even more violent. This is why Chancellor Merkel has been presenting the refugee problem as a “common national challenge” requiring the joint effort of the central government, the federal states, the communities and individual citizens. This view has been consistent with the attitude of a large portion of Germans who are willing to help refugees (see Appendix 2). At the same time, to anticipate the fears of many Germans, on 9 September 2015 during a budget debate at the Bundestag, Chancellor Merkel assured the public that integration of new immigrants will be a top priority issue. She did not want the mistakes made in the 1960s to be repeated. These mistakes led to the emergence of ‘parallel societies’ where basic principles of social coexistence are not respected.

Aside from the attempt to resolve the most striking problems, no major changes to the German asylum system should be expected. In this situation, the only possible solution to relieve Germany would be to shift some of its commitments towards ‘refugees’ onto other EU states. In practice, this would mean Berlin’s attempts to introduce a quota system and to transfer groups of immigrants to all other EU states according to certain quotas. Berlin is challenging the current regulations (Dublin III)[10] and stepping up pressure on other EU member states to agree to an adoption of new laws. Public announcements regarding willingness to help (which serve the purpose of boosting the image of Angela Merkel and Germany), as well as consistent use of the narrative which emphasises the divide between those EU states which have been willing to face the challenge (Germany, Austria, Sweden) and the rest of the EU, will be used to convince other EU members to shoulder some of the burden.

Appendix 1

Basic information regarding the German asylum law

- In what circumstances can a refugee be granted the right to stay in Germany?

- the right to asylum pursuant to Article 16a of the constitution;

- providing protection pursuant to the Geneva Refugee Convention, the European Convention on Human Rights and other international agreements;

- providing subsidiary protection, if required and possible;

- a ban on deportation pursuant to the United Nations Convention against Torture;

- temporary postponement of deportation if “travel is impossible due to legal or factual causes”.

- The asylum procedure

The process described below uses Berlin as example:

- A refugee comes to the Central Registration Office for Asylum Seekers of the Federal State Berlin, where they are registered.

- The refugee is assigned to a specific federal state according to the quota system.

- Next, they must visit a local unit of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, where they must submit an asylum application in person and obtain documents confirming that they are staying in Germany. During questioning, each individual aged 16 or older must specify their reasons for applying for asylum.

- Until a final decision is issued, the refugee must remain in the first contact centre for up to three months.

- When a positive decision is issued, responsibility for financing the refugee is shifted from federal state to community The refugee moves to a local refugee centre, even if the procedure regarding their asylum application is prolonged.

- Care provided to immigrants

Asylum seekers are accommodated in first contact centres, where they can stay for up to three months. After three months, they can move to community centres run by private companies or charity institutions, located in a federal state to which the specific refugee has been assigned.

Each asylum seeker is entitled to approximately 6.5 sq m of living space. To accommodate the growing number of asylum seekers, they are offered shelter in barracks, hospitals, tent camps and camping sites.

- Asylum seekers are entitled to:

- food, shelter, heating, clothes, healthcare, basic necessities and consumer products;

- pocket money (for personal expenditure)

- access to medical care in case of serious illness or pain (federal states Hamburg and Bremen have introduced obligatory health insurance for asylum seekers).

- Access to job market and education

Since 2014, asylum seekers have been entitled to education in German schools. Access to language classes has not been regulated, however.

Since 1 January 2015, asylum seekers have been entitled to access the German job market after three months of stay. However, precedence in employment is given to Germans, citizens of other EU states and other foreigners having a work permit. The principle of precedence is not respected in the case of graduates of universities and colleges qualified to perform jobs in which the workforce is scarce. Similarly, the principle does not apply to asylum seekers who have stayed in Germany for 15 consecutive months.

- A residential obligation

Pursuant to the law which came into force on 1 January 2015, an individual who submitted their asylum application can leave the city or region to which they had been assigned only on the basis of a special approval by local government. Otherwise, such an individual might be fined, and if they break the law again, they might be taken to court and imprisoned. Asylum seekers are not entitled to freely chose their place of residence, unless they have enough funds to support themselves.

- Church asylum

If an asylum seeker is at risk of expulsion, they can use the procedure of so-called church asylum (German: Kirchenasyl). Some church communities take in refugees whose deportation would be tantamount to “inhumane cruelty”. Using this procedure, an asylum seeker wins the time necessary for repeated processing of their asylum application.

Appendix 2

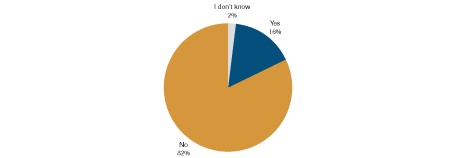

Opinion poll conducted on 4–6 August 2015 by the Forsa-Institut, commissioned by the Stern weekly

Are Germans particularly obliged to help refugees due to Germany’s history and the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis?

Do you approve of protests against taking in refugees?

Would you be willing to get involved in helping the refugees?

Are too many refugees coming to Germany?

[1] The full title of the law is The law on managing and limiting immigration and on regulating stay and integration of citizens of the European Union and of foreigners (Gesetz zur Steuerung und Begrenzung der Zuwanderung und zur Regelung des Aufenthalts und der Integration von Unionsbürgern und Ausländern, Zuwanderungsgesetz).

[2] https://www.gruene.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Bilder/Redaktion/30_Jahre_-_Serie/Teil_21_Joschka_Fischer/Rot-Gruener_Koalitionsvertrag1998.pdf

[4] Asylum procedure – see Appendix 1.

[5] The phenomenon of immigrants pretending to be Syrian has not been researched in statistical terms. It is certain, however, that over 80% of individuals submitting asylum applications have no identity documents. Due to the lack of documents and of the ability to determine the identity of an individual it is impossible to expel the ‘refugee’ (regardless of the final decision concerning their asylum application);

http://www.mdr.de/nachrichten/asylbewerber-ohne-ausweis100_zc-e9a9d57e_zs-6c4417e7.html

[6] According to data compiled by the European Commission, in 2013 75% of asylum applications submitted in Schengen states by citizens of the Western Balkan states were submitted in Germany. According to the EC, the most common reasons why these groups of emigrants leave their countries include poverty, unemployment, discrimination, lack of access to healthcare, social benefits and education, and (in the case of Albanians) family disputes.

[7] Factors which stimulate escalation of tension include: overcrowded refugee centres; the fact that ethnic and religious groups which are in conflict stay in one place; the fact that two thirds of the centres’ residents are men; boredom; worsening living conditions; frustration; increasing demands by ‘refugees’ and their impression of being discriminated against. This phenomenon has not been described in statistical terms, however, it has been confirmed by officials and employees of the centres; http://www.migazin.de/2015/08/21/kriminologe-warnt-vor-zunehmender-gewalt-in-erstaufnahmestellen/

[8] On 21 August 2015, following their meeting Angela Merkel and François Hollande called for a European response to the crisis caused by the influx of ‘refugees’. This would involve full implementation of all binding asylum laws by all EU states; establishment of centres to register refugees in Italy and Greece (immigrants who have to chance of being granted asylum or refugee status would be rejected and the remaining ones would be transferred to other EU states), introduction of common standards for refugee registration, accommodation, care and readmission, as well as equal division of duties. Germany’s increasing approval for the quota system, “universal citizen rights” and European solidarity has been a relatively new component of the German asylum policy and seems to be directly proportional to the increase in the number of refugees and to the problems related to this situation.

[9] http://www.bundeskanzlerin.de/Content/DE/Mitschrift/Pressekonferenzen/2015/09/2015-09-07-merkel-gabriel.html

[10] In late August 2015, German media reported that the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) had issued a new guideline regarding asylum applications submitted by citizens of Syria. According to this guideline, Syrians will not be covered by so-called Dublin III procedure and the office will not be trying to determine whether Germany is the first safe country in which they arrived having fled Syria. By 1 July 2015, 42,100 asylum applications were submitted by citizens of Syria and only 131 individuals were sent back to other countries.