The Turkish campaign in Germany. Rising tensions between Berlin and Ankara

The influx of migrants to Germany and the conclusion of an agreement between the European Union and Turkey intended at stopping migrants from coming to the EU have shown that Germany’s internal policy is being increasingly influenced by decisions made by the Turkish government. The agreement might have introduced new dynamics to German-Turkish relations and brought about closer co-operation between the two countries but the situation became seriously complicated following a failed coup d’état in Turkey in July 2016 and President Erdogan’s response to it. Mass arrests and repression in Turkey are seen in Germany as an instrument of consolidation of Erdogan’s power, which is increasingly morphing into an oppressive authoritarian regime. Turkey’s plan to change the country’s constitution and to hold a referendum on it is perceived in this context.

The three million-strong Turkish diaspora in Germany, of whom nearly a half have the right to vote, makes bilateral relations between the two countries important. Campaigns ahead of subsequent elections in Turkey increasingly lead to the transferral of Turkey’s internal conflicts to Germany and spark tensions between Berlin and Ankara. Recently, the dispute has grown fiercer because of a referendum campaign in Turkey which Turkish politicians are also running in Germany. As for Germany, the Bundestag election campaign has begun and public opinion is calling on the government to take firm action and to condemn the political purges in Turkey, which have also extended to those with dual German-Turkish citizenship. Chancellor Merkel has been forced to act with more determination towards Turkey while seeking an agreement regarding migration issues, security policy and the fight against terrorism. Her task will be made more difficult not only due to the Turkish government’s confrontational attitude but also due to pressure from the Social Democrats and opposition parties in Germany.

The critical factors in German-Turkish relations

The Turkish community in Germany is the factor which bears the largest impact on German-Turkish relations. It comes ahead of strong economic ties and security co-operation. It is estimated that approximately three million people of Turkish descent live in Germany, of whom 2.1 million hold Turkish citizenship[1]. This has a direct bearing on Germany’s internal policy. Firstly, following many years of disputes and despite fears of loyalty to the German state, in 2014 Germany introduced the right to hold dual citizenship for children from immigrant families born in Germany. This was meant to strengthen the ties which young Turkish people have with Germany. Intensive election campaigns are held by Turkish politicians, which both divides the Turkish community and also leads to chasms on the German political scene. Furthermore, Turkey’s internal conflicts are increasingly being carried over to Germany with demonstrations and even riots occurring (such as the ones on May 2015 in Karlsruhe, pitting supporters and opponents of President Erdogan against each other). In the Bundestag, issues regarding Turkey’s politics are gaining particular importance, which has been manifested by tensions around the commemoration of the massacre of Armenians[2].

The armed conflict between Turkey and the Kurdish terrorist organisation PKK has a direct impact on Germany’s internal security. With the intensification of the fighting against the PKK in Turkey, clashes between supporters and opponents of the two parties are also escalating (for example, the riots in March 2016 in Duisburg or in April 2016 in Cologne, Hamburg and Stuttgart). The German counter-intelligence has expressed concerns at these events[3]. The German security services have been warning against the influence the Turkish intelligence agency (MIT) has in Germany; the warnings have applied above all to manipulations of German public opinion with false information and the repression which MIT uses against Turkish opposition figures living in Germany[4].

German-Turkish relations are also shaped by strong economic ties. Germany is Turkey’s most important trading partner. One tenth of Turkey’s exports go to Germany totalling approximately 14 billion euros. There are approximately 6,200 German companies in Turkey and their trade in 2015 amounted to 37 billion euros[5]. Turkey’s attractiveness in terms of tourism is also significant—in 2015 approximately 5.5 million Germans visited Turkey, which represents 15% of all foreign tourists. However, both terrorist attacks and the failed coup have contributed to limiting the number of tourists in Turkey.

Turkey, as a NATO member state, is one of Germany’s key partners in the area of security issues. The Bundeswehr troops engaged in the resolution of the Syrian conflict are stationed in the Turkish town of Incirlik[6]. The police forces of both countries work together to stop people smuggling. Germany and Turkey have also declared they are willing to fight against terrorism together (11 Germans were killed in the attack in Istanbul in January 2016 and two Germans in January this year). However, the close relations and their special character have not changed Germany’s negative position on Turkey’s EU membership (see Appendix 1).

The migration agreement and Turkey’s increased assertiveness

Co-operation between Berlin and Ankara has been strengthened in the face of the migration crisis. The influx of refugees to Europe, and in 2015 particularly to Germany, has forced the government of Angela Merkel to work with President Erdogan more intensively. For Merkel the priority has been to limit the number of immigrants arriving in Germany due to increasingly serious political and social problems in the context of the migration crisis in Germany. Co-operation between Germany and Turkey culminated in the first intergovernmental consultations which were held in January 2016 (Berlin holds such consultations with Germany’s 11 most important partners). The consultations were preceded by the visit of Chancellor Merkel during the Turkish election campaign (October 2015) which was interpreted as an expression of support for President Erdogan’s party.

The agreement between the EU and Turkey (signed in March 2016), apart from the immediate objective to reduce the migration pressure to Europe, might have strengthened German-Turkish relations and become the driving force behind them. However, despite Germany’s expectations, the agreement has become the source of mutual accusations and has provided the impulse for a dispute. Turkey has reproached the EU for not disbursing the promised funding (6 billion euros by 2018) and the lack of will to deliver on its promise to liberalise the visa regime for Turkish citizens. Germany has stated that it will fulfil its promise only when Turkey meets all requirements set by the European Commission. Ankara’s opposition to introducing the changes in the Turkish anti-terrorism law, which the EU had called for, has become the main bone of contention[7].

Although Turkey has threatened to break off the agreement with the EU on many occasions, it is still in force[8]. The synergy of the two processes has contributed to alleviating the migration pressure; the EU-Turkey agreement and better border controls of the Balkan migration route[9]. Should Turkey breach the agreement, the German Ministry of Finance has drafted a plan which allows for tight border controls on the Balkan route and on selected borders in the Schengen zone. A temporary exclusion of Greece from the Schengen zone would also be considered. Germany would opt for full protection of the maritime border between Turkey and Greece by the European Border and Coastal Guard. Additionally, other corrective measures would be taken should the agreement with Turkey fall apart, such as the establishment of new temporary camps for refugees in Greece. Germany also has high hopes regarding the quotas of refugees the EU member states would take in, believing that financial sanctions would be used in order to force the EU countries to agree to adopt this mechanism[10].

Even though Germany has prepared solutions that would be implemented should the agreement be breached, the deal with Turkey is of great political importance to Germany. It allows Germany to maintain the narrative about the ‘European regulation’ of the migration crisis which does not exclude any country, contrary to stepping up border controls on the Balkan route in the teeth of Greek opposition. The agreement also proves that Chancellor Merkel is committed to limiting the number of refugees arriving in Germany. Attention has been drawn to the positive role she has played in resolving this stage of the migration crisis, in particular ahead of the Bundestag election scheduled for September this year.

A change following the failed coup

The crisis in relations between Germany and Turkey came in response to President Erdogan’s reaction to the attempted coup d’état in Turkey in July 2016. Germany perceives the measures he has taken in retaliation as actions serving above all to consolidate his power. While Germany has condemned the coup plotters, Turkey believes it has done so rather reluctantly and Angela Merkel was not prepared to personally support President Erdogan. Furthermore, Germany refuses to provide Turkey with information about people and institutions allegedly linked to the Fethullah Gülen movement; Turkey accuses Gülen of preparing the coup[11]. Turkey has for a long time been accusing Germany of tolerating the activity of terrorist organisations in Germany (e.g. the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, the PKK) and of the ‘insubordination’ of the German television station which broadcast a vulgar poem ridiculing Erdogan. Germany has frequently criticised the violation of democracy in Turkey, Erdogan’s ruthless fight against the PKK and Turkey’s influence on the Turkish diaspora in Germany. In 2016 the German ambassador to Ankara was summoned to the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs three times and Turkey temporarily withdrew its representative in Berlin.

German criticism of Turkey reached its peaked following Ankara’s arrest of six German citizens, among them a Die Welt journalist Deniz Yücel, as part of Turkey’s fight against the coup plotters[12]. Turkey has accused him of spreading terror and inciting hatred, and President Erdogan has publicly charged him with espionage for Germany. Germany has rather limited possibilities to help its citizens since four of them (including Yücel) also hold Turkish citizenship and Turkey considers them to be solely Turkish citizens (deprived of the right to consular protection). In addition, relations between the two countries have been affected by an increased number of applications for asylum submitted by Turkish citizens in Germany. Between January and November 2016 5,166 people, including140 diplomats and Turkish military officials stationed in NATO bases in Germany, applied for asylum in Germany[13]. Previously approximately 1,800 applications were submitted per year. The secretary of state in the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Michael Roth (SPD), declared that Germany would ‘support all critics of the regime in Turkey’. This provided a certain level of encouragement to seek asylum in Germany[14]. Germany’s accusations of Turkey supporting terrorism have only added fuel to the fire. They leaked from the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ internal documents in August 2016 and led to another escalation in tensions between Berlin and Ankara[15].

Germany – a vital constituency in the Turkish election

The German-Turkish crisis caused by Erdogan’s reaction to the coup attempt and Turkey’s unprecedented verbal aggression towards German politicians has been the most serious in years and has grown stronger with the election campaign[16]. It also has an impact on the development of the Bundestag election campaign in Germany.

For Turkey, Germany is one of the vital constituencies—after Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir it is the fourth largest constituency with approximately 1.4 million people having the right to vote[17]. In the constitutional referendum in Turkey scheduled on 16th April the vote from Germany may tip the balance since surveys regarding support for constitutional changes advocated by the Turkish president indicate that he does not have a clear majority[18]. He could gain dominance due to the vote of Turks living in Germany since in the previous elections the majority of them had backed the Justice and Development Party (AKP). In the 2015 parliamentary election the support for the ruling party reached 60%, which was the highest figure outside Turkey. Two organisations, in practice closely affiliated to the AKP, serve Erdogan in his efforts to mobilise Turkish voters in Germany: the Union of European Turkish Democrats (UETD) and the Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB, see Appendix 2).

In Germany speeches made by politicians from Ankara are the most important element in the mobilisation of Turkish voters. At the beginning of March several Turkish ministers were forbidden to make election speeches in Germany, on the pretext of a legal restriction regarding the security of public gatherings. The decisions were made by the local governments (including those in Cologne and Gaggenau), where election rallies were scheduled to be held. The states and opposition politicians criticised the federal government for shifting responsibility for foreign policy onto local governments. Previously, despite a series of controversial statements, the election rallies for Turks had been tolerated by the government in Berlin[19]. This approach changed with Germany’s growing concern with the transformation of Turkey’s political system, the intensifying aggressiveness of Turkish rallies, and the ongoing election campaign in Turkey. The German government is worried both about the loyalty of citizens holding dual citizenship, and that a large section of the German public opinion will interpret the agreement for Turkish election campaigns to be held in Germany as an expression of support for authoritarian changes in Turkey.

Although the German government is critical of the development of the internal situation in Turkey and considers Turkish verbal attacks to be ‘unacceptable’, in the context of the ongoing election campaign in Germany there is no coherent position on Turkish activities in Germany. Chancellor Merkel will have to choose between criticising Turkey more strongly, which the majority of German society would expect, and appeasing the partner which is important for Germany’s migration and security policies in the Middle East. 81% of Germans believe that Berlin should be firmer in responding to Turkey’s activities (the survey conducted by Emnid on 5th March this year). However, in the opinion of Chancellor Merkel, an excessively severe criticism of the measures undertaken by President Erdogan may be counter-productive and strengthen support for the changes in Turkey’s political system in the Turkish diaspora in Germany. The lack of a firm reaction will cause suspicions that Chancellor Merkel is dependent on Turkey, which may have a particularly negative impact on the result of the CDU in this year’s election. For these reasons Chancellor Merkel dismissed President Erdogan’s comparison of Germany’s actions to the practices of the ‘national-socialist government’ as ‘absurd and misplaced’[20] and the head of the Chancellor’s Office, Peter Altmaier, threatened to prohibit election rallies organised by Turkish politicians in Germany [21]. The SPD, the CDU’s main rival in the parliamentary election and its coalition partner, has been using speeches made by Turkish politicians in its election campaign. The SPD (among them foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel and justice minister Heiko Maas) are trying to set themselves apart from Chancellor Merkel’s position, which to date has been quite balanced, by firmly criticising Turkish politicians. The CSU, the Green Party and the Left Party hold a similar position, calling for a complete ban on election presentations by Turkish politicians. The Turkish diaspora in Germany usually votes for the SPD but, due to the small percentage of this group among all eligible voters in Germany (approximately 2%), its preferences do not have a real impact on election results in Germany.

The outlook: the conflict is in nobody’s interest

In the medium term German-Turkish relations will be shaped both by growing distrust and the necessity for close co-operation in selected areas. Apart from the economy, this applies above all to preserving the migration agreement since it would be costly for Chancellor Merkel in political terms if Turkey terminated it before the election in Germany. Other areas of further co-operation will encompass attempts to resolve the conflict in Syria, limiting the smuggling of migrants, and the fight against terrorist groups. The growing scepticism towards the changes occurring in Turkey will not rule out co-operation in selected sectors. Further co-operation will be based on the present modus vivendi because there is no hope that the government in Ankara will change in the short term and that Turkey’s policy towards the EU will be revised.

Germany will also opt for a continuation of the EU-Turkey accession negotiations since it treats that as one of the few instruments of pressure in order to change Turkey’s policy. However, for a section of German politicians, Turkey’s authoritarian tendencies prove that Ankara should not join the EU and this is causing further tensions between the two capitals.

While negotiating the migration agreement, Germany has for the first time been confronted with Turkey’s perspective of negotiating from a position of strength and Germany was not prepared for this. Ankara may use this model of talks in further negotiations with Germany and take advantage of the Turkish minority in Germany in order to make threats and to escalate tensions between the two countries. Germany also fears the intensified activity of Turkish organisations in Germany closely affiliated to Erdogan, and their impact on Germany’s internal policy. Merkel, who was accused of being submissive towards Turkey last year, will be forced to show more assertiveness in the election year. She will thus try to demonstrate her independence and to consolidate her voters, who are critical of Erdogan, and limit their defection to other parties. Seeing the need to have more room for manoeuvre in its relations with Turkey, Germany will be inclined to increase its involvement in stepping up the security of EU borders and maintaining effective border controls along the Balkan migration route. Additionally, in order to put Ankara under pressure, Germany will use the instruments of development assistance and financial support, which are quite important for Turkey.

Appendix 1. Germany and Turkey’s membership in the EU

Turkey has been seeking EU membership since 1963 when it gained the status of associated member. Accession aspirations have been shaping Turkey’s co-operation with the EU, including with Germany, since the beginning. Chancellor Angela Merkel is sceptical of Turkey’s EU membership and for this reason Germany has been blocking the opening of subsequent negotiation chapters with Ankara (negotiations started in 2005). Berlin has agreed for the accession negotiations to be accelerated as part of the migration deal, but does however remain opposed to Turkey joining the EU. In Germany two approaches to Turkey’s EU membership can be distinguished. In the first one, closer to Chancellor Merkel’s party line, Turkey’s accession to the EU should be replaced with ‘privileged partnership’ with the EU. The Social Democrats, the Green Party and the Left Party hold the second position, which is more in favour of Turkey’s EU membership. They opt for Turkey’s full accession to the EU. The approach of these parties to Turkey’s accession to the EU may lead Germany to open further negotiation chapters should these parties form a coalition following the parliamentary election in 2017.

Germany is not ready to make negotiations concessions to Turkey due to the migration agreement. In Berlin there are suggestions that, given Brexit and the possible changes in the EU, two circles of EU integration should be established. The first one would be reserved for current EU members, and the second circle could group together the UK and Norway and also Turkey. The member states in the second circle would gain access to the common market and to security co-operation, including the prevention of illegal migration. In exchange for this Turkey would contribute to the EU budget, but without the full right to participate in making decisions as these would be excluded from the second circle of EU integration[22]. This solution would be an intermediate form of EU membership and it would fulfil Turkey’s ‘privileged partnership’ with the EU.

The German government has also not agreed to the acceleration of the liberalisation of the visa regime between the EU and Turkey without Turkey meeting all the conditions required by the European Commission. German society also supports this stance. 69% of the respondents demand that the talks about the liberalisation of the visa regime with Turkey be stopped (according to a survey conducted by ARD-DeutschlandTrend in August 2016). The bone of contention is Ankara’s opposition to introducing changes in the anti-terrorism law, which is required by the EU[23]. It is quite unlikely that the visa requirement for Turks will be lifted before the Bundestag election to be held in September 2017. For Germany the liberalisation of the visa regime presents an increased risk of illegal migration and, consequently, a threat to its welfare system. The prerequisite for changing the current visa regulations will be an additional requirement to introduce a mechanism which will make it possible to temporarily suspend the liberalisation of the visa regime should the new system be abused. The adoption of an identical provision by the European Parliament was necessary in order to liberalise the visa regimes for Ukraine and Georgia in 2016.

Appendix 2. Activity of UETD and DITIB in Germany

The Union of European Turkish Democrats (UETD) and the Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB) are the most important Turkish organisations in Germany, and are closely affiliated to President Erdogan’s party. DITIB is formally affiliated to the state institution the Presidency of Religious Affairs, not directly with the AKP. Both organisations have their headquarters in Cologne. UEDT is above all politically-oriented, it organises rallies of Turkish AKP politicians in Germany, among its other activities. DITIB is a religious organisation and groups together approximately 900 mosques (out of a total of 2,350 mosques in Germany). A section of German politicians (among them Armin Schuster from the CDU, a member of the Committee on Special Services, and Volker Beck from the Green Party) reproach the two organisations for strengthening the AKP’s ascendancy in Germany, running campaigns against German members of parliament voting in favour of the Bundestag resolution regarding the genocide of Armenians, and spying on associates working with Fethullah Gülen (whom Ankara accuses of initiating the coup attempt in July 2016). In January 2017 Germany’s prosecutor general launched an investigation into the DITIB’s espionage for Turkey[24].

[1] C. Sydow, Debatte über den Doppelpass – das sind die Fakten, Der Spiegel, 5.08.2016, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/deutschtuerken-doppelte-staatsbuergerschaft-das-sind-die-fakten-a-1106363.html

[2] In response to the Bundestag’s resolution of June 2016 which commemorated the massacre of Armenians, the government in Ankara did not issue entrance permits for German politicians who wanted to visit the base in Incirlik where Bundeswehr troops are stationed. The dispute was resolved after the German government spokesman admitted that the resolution was not legally binding and was only an expression of the parliament’s opinion. It was Angela Merkel who insisted on this clarification as a precondition for letting German parliamentarians enter Turkey. There were voices in Germany arguing that it is necessary to change the location of the base and to remove it from Turkey. However, towards the end of November, Chancellor Merkel made it clear that the base’s current location should not be disputed and that Germany is not intending to move its troops elsewhere (to Jordan, Kuwait or Cyprus).

[3] Spannungen zwischen rechtsextremistischen / nationalistischen Türken und Anhängern der PKK in Deutschland, BfV-Newsletter No. 2/2016 – Thema 6, https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/newsletter/newsletter-archive/bfv-newsletter-archiv/bfv-newsletter-2016-2/bfv-newsletter-2016-02-06

[4] The counter-intelligence has set up a special group in order to monitor MIT’s activity in Germany. Compare, Gezielte Falschmeldungen aus Ankara?, 2.12.2016, https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/tuerkischer-geheimdienst-101.html

[5] Türkei: Beziehungen zu Deutschland, January 2017, http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/sid_0ED526BFFBA9DBF066787F24FE6D39DB/DE/Aussenpolitik/Laender/Laenderinfos/Tuerkei/Bilateral_node.html#doc336370bodyText3

[6] J. Gotkowska, K. Frymark, Germany’s engagement in the resolution of the Syrian conflict, OSW Commentary, 25.01.2016, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2016-01-25/germanys-engagement-resolution-syrian-conflict

[7] M. Chudziak, Turkey/EU: playing hardball on visa liberalisation, OSW Analyses, 11.05.2016,

[8] See e.g. Turkey's EU minister says migrant readmissions may end without visa deal, 18.10.2016 http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-turkey-idUSKCN12I26L

[9] Both processes are overlapping and on the one hand prove that Turkey is determined to patrol its own coast and to combat smugglers (since 20th March 2016 when the EU-Turkey agreement came into force, the number of migrants arriving from Turkey to the Greek islands has fallen by as much as 97%, according to Frontex). On the other hand, sending the message, that has spread rapidly in social media, about tighter controls on the Balkan route has contributed to reducing the migration pressure.

[10] Compare, Bundesregierung plant für mögliches Scheitern des Flüchtlingsdeals, 19.08.2016, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/tuerkei-fluechtlingsdeal-bundesregierung-plant-fuer-moegliches-scheitern-a-1108494.html Berlin is concerned about migrants from Africa who are arriving in Italy and possibly moving on to Germany. Germany is determined to strengthen the internal borders of African countries; this was the purpose of Angela Merkel’s visit to Niger and Mali in October 2016 and to Tunisia and Egypt in February and March this year. See K. Frymark, Germany wants migrants to remain in Africa, OSW Analyses, 19.10.2016, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2016-10-19/germany-wants-migrants-to-remain-africa

[11] J. Diehl, Wie die Türkei deutsche Sicherheitsbehörden bedrängt, Der Spiegel, 21.02.2017, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/fethullah-guelen-tuerkei-uebt-druck-auf-deutsche-sicherheitsbehoerden-aus-a-1135448.html

[12] Sechs Deutsche in türkischer Haft, FAZ, 1.03.2017, http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/neben-deniz-yuecel-sind-5-weitere-deutsche-in-tuerkischer-haft-14904655.html

[13] Mehr türkische Diplomaten bitten um Asyl, http://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/tuerkei-diplomaten-asyl-101.html

[14] Deutschland bietet verfolgten Türken Asyl an, 8.11.2016, http://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2016-11/auswaertiges-amt-tuerkei-asyl-angebot

[15] When this classified document was leaked, the dispute between the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Chancellor’s Office over the assessment of the threat from the Middle Eastern countries once again surfaced. The ministry distanced itself from the accusation that Turkey supports terrorism (the ministry, contrary to the usual situation, had not been included in the process of developing the assessment). In February 2016 the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not approve the assessment prepared by the Chancellor’s Office regarding Saudi Arabia, with which it had developed close co-operation. According to the assessment Riyadh was a destabilising factor in the region.

[16] 11 members of parliament from the Left Party were granted police protection since they had received threats after voting in favour of the Bundestag resolution which qualified the massacre of Armenians as genocide. The German Ministry of Foreign Affairs (in a report that has not been made public) discouraged German politicians of Turkish descent from visiting Turkey due to the inability to guarantee them safety. Compare, Drohungen: Türkischstämmige Bundestagsabgeordnete unter Polizeischutz, 12.06.2016, http://www.deutsch-tuerkische-nachrichten.de/2016/06/526349/drohungen-tuerkischstaemmige-bundestagsabgeordnete-unter-polizeischutz/

[17] Since the 2014 presidential election in Turkey the Turkish diaspora in Germany can vote not only in consular establishments but also in specially established halls (e.g. at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin), which facilitates voting and increases turnout.

[18] As part of the constitutional changes the present parliamentary system will shift to a presidential system under which the president will be granted full executive power, and the competences of parliament, the judicial system and supervisory institutions will be substantially reduced. The reform of the political system is set to be the culmination of the long-lasting efforts of the ruling party and President Erdogan to change the political structure of the state. See, M. Chudziak, Constitutional reform in Turkey: the President takes it all, OSW Analyses, 25.01.2017, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2017-01-25/constitutional-reform-turkey-president-takes-it-all

[19] The controversies caused by President Erdogan’s speeches were linked to his words in: Cologne in 2008 where he stated that “assimilation is a crime against humanity’ and in 2011 in Düsseldorf where he claimed that ‘Turkish children should first learn Turkish, then German’. Both statements he made have led to protests from German politicians. Erdoğans Rede erzürnt deutsche Politiker, Die Welt, 28.02.2011, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article12665248/Erdoğans-Rede-erzuernt-deutsche-Politiker.html

[20] Bundesregierung weist NS-Vergleich zurück, 9.03.2017, https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Artikel/2017/03/2017-03-06-deutsch-tuerkisches-verhaeltnis.html

[21] Kanzleramtschef droht türkischen Politikern mit Einreiseverbot, 15.03.2017, http://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2017-03/peter-altmaier-tuerkei-einreiseverbot-wahlkampf

[22] Europe after Brexit: A proposal for a continental partnership, 29.08.2016, http://bruegel.org/2016/08/europe-after-brexit-a-proposal-for-a-continental-partnership/

[23] M. Chudziak, Turkey/EU: playing hardball on visa liberalisation, OSW Analyses, 11.05.2016, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2016-05-11/turkey/eu-playing-hardball-visa-liberalisation

[24] Imame spionieren in Deutschland, NZZ, 25.02.2017, https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/imame-spionieren-in-deutschland-du-sollst-nicht-spitzeln-ld.147588 Compare also, Erdoğans Einfluss in Deutschland ist riesig, 9.06.2016, http://www.dw.com/de/Erdoğans-einfluss-in-deutschland-ist-riesig/a-19317938 and, Erdoğans Lobby in Deutschland, 7.06.2016, http://www.tagesspiegel.de/themen/agenda/einfluss-der-tuerkei-Erdoğans-lobby-in-deutschland/13695612.html

Appendix 1. Germany and Turkey’s membership in the EU

Turkey has been seeking EU membership since 1963 when it gained the status of associated member. Accession aspirations have been shaping Turkey’s co-operation with the EU, including with Germany, since the beginning. Chancellor Angela Merkel is sceptical of Turkey’s EU membership and for this reason Germany has been blocking the opening of subsequent negotiation chapters with Ankara (negotiations started in 2005). Berlin has agreed for the accession negotiations to be accelerated as part of the migration deal, but does however remain opposed to Turkey joining the EU. In Germany two approaches to Turkey’s EU membership can be distinguished. In the first one, closer to Chancellor Merkel’s party line, Turkey’s accession to the EU should be replaced with ‘privileged partnership’ with the EU. The Social Democrats, the Green Party and the Left Party hold the second position, which is more in favour of Turkey’s EU membership. They opt for Turkey’s full accession to the EU. The approach of these parties to Turkey’s accession to the EU may lead Germany to open further negotiation chapters should these parties form a coalition following the parliamentary election in 2017.

Germany is not ready to make negotiations concessions to Turkey due to the migration agreement. In Berlin there are suggestions that, given Brexit and the possible changes in the EU, two circles of EU integration should be established. The first one would be reserved for current EU members, and the second circle could group together the UK and Norway and also Turkey. The member states in the second circle would gain access to the common market and to security co-operation, including the prevention of illegal migration. In exchange for this Turkey would contribute to the EU budget, but without the full right to participate in making decisions as these would be excluded from the second circle of EU integration[1]. This solution would be an intermediate form of EU membership and it would fulfil Turkey’s ‘privileged partnership’ with the EU.

The German government has also not agreed to the acceleration of the liberalisation of the visa regime between the EU and Turkey without Turkey meeting all the conditions required by the European Commission. German society also supports this stance. 69% of the respondents demand that the talks about the liberalisation of the visa regime with Turkey be stopped (according to a survey conducted by ARD-DeutschlandTrend in August 2016). The bone of contention is Ankara’s opposition to introducing changes in the anti-terrorism law, which is required by the EU[2]. It is quite unlikely that the visa requirement for Turks will be lifted before the Bundestag election to be held in September 2017. For Germany the liberalisation of the visa regime presents an increased risk of illegal migration and, consequently, a threat to its welfare system. The prerequisite for changing the current visa regulations will be an additional requirement to introduce a mechanism which will make it possible to temporarily suspend the liberalisation of the visa regime should the new system be abused. The adoption of an identical provision by the European Parliament was necessary in order to liberalise the visa regimes for Ukraine and Georgia in 2016.

Appendix 2. Activity of UETD and DITIB in Germany

The Union of European Turkish Democrats (UETD) and the Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB) are the most important Turkish organisations in Germany, and are closely affiliated to President Erdogan’s party. DITIB is formally affiliated to the state institution the Presidency of Religious Affairs, not directly with the AKP. Both organisations have their headquarters in Cologne. UEDT is above all politically-oriented, it organises rallies of Turkish AKP politicians in Germany, among its other activities. DITIB is a religious organisation and groups together approximately 900 mosques (out of a total of 2,350 mosques in Germany). A section of German politicians (among them Armin Schuster from the CDU, a member of the Committee on Special Services, and Volker Beck from the Green Party) reproach the two organisations for strengthening the AKP’s ascendancy in Germany, running campaigns against German members of parliament voting in favour of the Bundestag resolution regarding the genocide of Armenians, and spying on associates working with Fethullah Gülen (whom Ankara accuses of initiating the coup attempt in July 2016). In January 2017 Germany’s prosecutor general launched an investigation into the DITIB’s espionage for Turkey[3].

[1] Europe after Brexit: A proposal for a continental partnership, 29.08.2016, http://bruegel.org/2016/08/europe-after-brexit-a-proposal-for-a-continental-partnership/

[2] M. Chudziak, Turkey/EU: playing hardball on visa liberalisation, OSW Analyses, 11.05.2016, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2016-05-11/turkey/eu-playing-hardball-visa-liberalisation

[3] Imame spionieren in Deutschland, NZZ, 25.02.2017, https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/imame-spionieren-in-deutschland-du-sollst-nicht-spitzeln-ld.147588 Compare also, Erdoğans Einfluss in Deutschland ist riesig, 9.06.2016, http://www.dw.com/de/Erdoğans-einfluss-in-deutschland-ist-riesig/a-19317938 and, Erdoğans Lobby in Deutschland, 7.06.2016, http://www.tagesspiegel.de/themen/agenda/einfluss-der-tuerkei-Erdoğans-lobby-in-deutschland/13695612.html

Appendix 3. Trade between Germany and Turkey

Own analysis based on data from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany

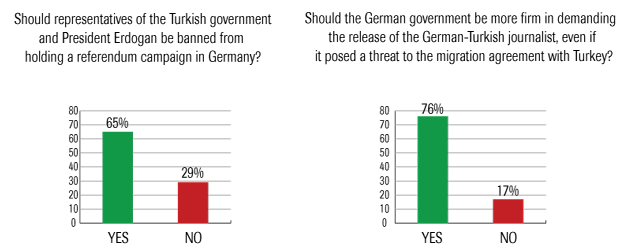

4. Public opinion survey regarding the Turkish referendum campaign in Germany

Source: Forsa Institute (Analysis for Stern Magazine, March 2017)