Predictability lost: the German political scene after the elections

Both in Germany and abroad, the commentary on the recent elections in Germany has been dominated by the analysis of the results scored by the anti-immigrant and anti-Islam Alternative for Germany (AfD), particularly in the eastern and southern parts of the country. The party had been almost certain to make it to the Bundestag long before the 24 September elections: the result it has just scored was only slightly better than what the pre-election polls suggested. The results scored by the two mass parties, the CDU/CSU and the SPD, were much worse than the poll predictions. It is these parties’ results that offer an insight into the evolution of German voters’ political identities. Moreover, they are of key importance when assessing and predicting the upcoming events on the German political scene. In the short term, it is unlikely that the old parties will break up or that new ones will emerge. However, it is likely that the traditional mass parties will continue to lose their electoral base. Parties with a distinct ideology such as the AfD, which is likely to be an uncompromising opposition party, may continue to gain ground. Due to the AfD’s presence in the Bundestag, the language of public debate in Germany is likely to become increasingly aggressive, and the narratives of the AfD and the remaining parties are diverging to an ever greater extent.

The crisis of the mass parties

The election results mainly indicate the magnitude of the crisis affecting the two mass parties (Volksparteien), the CDU and the SPD. Despite their victory, the Christian Democrats’ result turned out to be much worse than in 2013 (a drop of 8.9%). Stanislaw Tillich, the prime minister of Saxony and a close party collaborator of Angela Merkel, said that the Christian Democrats had failed to tackle the issues which the public is really concerned about. He called for a new start, took responsibility for the CDU’s poor result in Saxony, and stepped down from the office of prime minister. The SPD, for its part, has scored its worst result since the end of World War II. To avoid being held accountable for the defeat, during the post-election evening the head of the Social Democratic party chose to retreat by advancing, and announced that under his leadership the party would go into opposition. By doing so, he focused the party’s internal debate on programme issues instead of personnel issues.

The CDU and the SPD began to lose their duopoly on the German political scene in the first decade of the 21st century. Back in 1990, the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats had 790,000 and 943,000 members respectively, whereas in 2016 those figures were 431,000 and 432,000. In recent years, the dwindling of their stable electorate has been accompanied by an increase in the proportion of voters who make their electoral decisions at the last minute, guided by their emotions. A week ahead of the recent elections to the Bundestag, 40% of voters did not know what party they would vote for; back in 1980, the corresponding proportion was 20%.

The German voters’ increasingly weak loyalty towards the two political giants results from a number of factors:

1. Since 2005 the manifestos of the SPD and the Greens have been undergoing an ongoing unification. This is evident, for example, in the introduction of the minimum wage, dual citizenship, a professional army, rescuing the eurozone and the energy transformation programme. These initiatives have enabled the Christian Democrats to build a strong position in the centre of the political scene. At the same time, it has made it increasingly difficult to tell the difference between the manifestos of the CDU and the SPD, and even the Greens. This line of development has been a disappointment for conservative CDU voters. In 2013, an alternative emerged for them in the form of the AfD. Research on the transfer of voters indicates that the biggest number of voters this anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic party has seized from other parties were former CDU voters (the research did not cover the mobilisation of traditional non-voters). Detailed polls regarding the main characteristics of specific parties confirm the lack of a clear-cut profile for the mass parties: 50% of Germans believe that Angela Merkel is the CDU/CSU’s main asset, while at the same time 48% say that it is difficult to clearly define her political views. For 74% of the respondents, the SPD is a party which does not speak of anything that could be of interest to the public. As many as 81% of the respondents argue that the post-Communist, extreme left-wing Left Party is unable to solve any problems, but at least it calls a spade a spade; and 49% say that the AfD understands the problem of insecurity many Germans experience and treats it seriously[1].

2. The reforms of the job market and the welfare system known as Agenda 2010, carried out by Gerhard Schröder (SPD), brought an improvement of Germany’s economic situation. However, traditional SPD voters considered them a betrayal of leftist ideals, and since then the Social Democrats have failed to regain their former credibility and trust. This is particularly important in the context of the fact that since 2007 they have had a strong political competitor in the form of the Left Party, which looks for votes from groups that consider themselves socially excluded.

3. As a result of demographic, social and economic changes, the electorates of the two mass parties have become increasingly similar to each other. The traditional, stereotype-based division, according to which the working class votes for the SPD and the small-town middle class votes for the CDU, is no longer confirmed by research data[2]. Research conducted by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) indicated that the main differences involve the place of residence (the SPD has more voters in urban areas) and the voters’ fears (according to CDU voters, the biggest threats to Germany are crime and migrations, whereas according to SPD voters, it is climate change). The political affiliations of an increasing proportion of voters are not determined by their profession or religion but by other social characteristics and aspirations. The fact of formally belonging to the working class, combined with a relatively high standard of living typical of the middle class, has caused the traditional proletarian ethos to dwindle rapidly. Similarly, in the context of a society becoming increasingly secularised, the fact of formally belonging to a given church is no longer a criterion which determines how one votes.

4. Due to intra-party differences between the politicians active at state level and at federal level, voters are losing orientation as regards the parties’ political profiles. Both the CDU and the SPD tolerate individuals within their ranks who frequently have totally opposite views. Such internal divisions are best illustrated by the example of state elections in which the views of local activists, regarding for example migration policy, are frequently considerably different from the concepts supported by federal-level politicians. For example, ahead of the 2016 elections in the North Rhine-Palatinate, Julia Klöckner, the head of the local CDU organisation, openly criticised Angela Merkel’s policy during the migration crisis. Thilo Sarrazin, a former SPD politician, is one of the most prominent and controversial critics of the ‘multi-kulti’ concept of the state open to immigrants.

It is noteworthy that the weakening trends recorded for the mass parties has also affected those groups which have the status of mass parties in selected regions instead of the country as a whole, namely the CSU in Bavaria and the Left Party in the eastern part of Germany. The CSU, which is the CDU’s more conservative (in its world outlook) and more pro-social sister party, scored 38.8% of the votes in the elections to the Bundestag in Bavaria. This result is better than the overall result of the Christian Democrats nationwide, but it is still below the expectations of the party, which considers itself a ‘state party’ (Staatspartei)[3] in its federal state, and won 49.3% of the votes there four years ago. The relatively poor result scored by the CSU was due to the actions of Horst Seehofer, the prime minister of Bavaria and head of the CSU, during the migration crisis, when he criticised Angela Merkel’s policy. Paradoxically, he lost votes from both opponents and supporters of the Chancellor. According to the former group, he was too lenient, whereas according to the latter he was dishonest towards Ms Merkel. This translated into increased support for the anti-immigrant AfD and the pro-immigrant Left Party and the Greens.

In the eastern part of Germany, the Left Party has lost its status as the second most prominent political force (after the CDU), with the AfD replacing it. Research shows that previous Left Party voters chose the AfD because they were discouraged by the Left Party’s excessively pro-immigrant views.

The sluggish changes within the big parties

The crisis affecting the CDU and the SPD does not mean that there is no longer room for mass parties on the German political scene. The attempt – despite the formal differences in party manifestos – to create a government coalition composed of the CDU/CSU, the FDP and the Greens, as well as the support this configuration recently enjoyed (57%, an increase of 34% compared to a poll conducted ahead of the elections), suggest that the present party situation does not reflect the real divisions in German society. The poll reflects a situation in which the liberal wing of the CDU has more in common with the Greens, the conservative wing of the SPD and the freedom-oriented faction of the FDP, than with the CSU or the more conservative members of Angela Merkel’s CDU.

It is unlikely that in the immediate future the old parties will break up, or that new parties will emerge. The mass parties will continue to try to combine their divergent ideological views. They will tolerate many different lines of thinking, especially at the state level, and make tactical gestures towards those voters who are more inclined to support the right and left sides of the political scene respectively. Immediately after the elections, several CDU members called on the party to become more open to right-wing voters, and even to replace Angela Merkel with a new party head[4]. However, a poll conducted among the present party supporters showed that 33% of CDU voters favour this type of rightward turn, and 55% are against it. 98% of the surveyed group do not want any changes in the party leadership[5]. These results have been welcomed by the party’s liberal wing because they strengthen Angela Merkel’s position ahead of coalition talks.

The situation within the SPD is more complex. Schulz has managed to postpone personnel debates and the assessment of the reasons for the party’s electoral defeat, but only until December 2017 at the latest. This is when the party members will hold a federal-level convention. To maintain his post as head of the SPD, Schulz will have to agree to personnel and programme concessions proposed by the party’s radical left wing. This group is satisfied with the fact that the party is now in opposition, but at the same time it is demanding that the party clearly condemn Agenda 2010, and has requested personnel changes in the party’s governing bodies. Schulz is aware that an excessively hard turn to the left will discourage further moderate voters from the SPD, while not necessarily meaning that the portion of its former electorate that chose to support the Left Party could be regained.

Regardless of what decisions will be taken in the short term, the two parties will have to tackle a problem which has already become evident: fewer votes cast in favour of specific parties are tantamount to smaller state subsidies and, as a result, less potential to retain the present voters and win new ones[6]. This system would favour parties with a strong ideology, such as the Greens, the Left Party and the AfD (and possibly the CSU, if the Bavarians distance themselves from Chancellor Merkel).

The party non grata

The SPD will be the biggest opposition caucus in parliament, but it is the AfD that will be the real opposition in the present political situation. The AfD was created in 2013 as an anti-establishment party opposing aid programmes for eurozone countries such as Greece. Over four years, it has managed to bring its representatives into the European Parliament and to 14 of the 16 local parliaments in Germany. In the meantime, the party, which was initially established by economics professors who had become disenchanted with the Christian Democrats and the FDP, has become strongly rightwards-oriented, and won over its voters by using anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic rhetoric.

The AfD is the only party to have achieved a clear success in the elections to the Bundestag. The party has brought 94 deputies into parliament despite its internal conflicts, attempts to isolate it, and a certain hostility on the part of mainstream media. This was possible not only due to the ‘social-democratisation’ of the CDU and the opening up of a niche on the right of the political scene. In its campaign, the AfD referred to certain issues which broke taboos and tested the boundaries of political correctness. At the same time, it took care to present itself as a party with no links to the neo-Nazis (the party’s procedures provide for checking the biographies of candidate members for any affiliation to neo-Nazi organisations), although it has never condemned such groups en bloc. Alongside this, the party leaders regularly emphasised the importance of the problem of crimes committed by immigrants, and demanded that the heroic behaviour of the ‘German soldier’ in two world wars be honoured. It would be no exaggeration to argue that it is because of the AfD that such attitudes are gaining ground and are no longer a source of shame. This trend is also a manifestation of the objections of increasingly numerous groups of voters towards the identity policy pursued by Angela Merkel, according to which nationality is more of a formal term synonymous with citizenship. At the same time, Chancellor Merkel, the mainstream parties and media have lost the so-called Deutungshoheit, that is, the monopoly on how to interpret events. This was possible due to the spread of electronic media which have absorbed the anti-establishment narrative. The state’s institutions and media are no longer able to successfully criticise their opponents. On the contrary, attempts to criticise only confirm the AfD’s narrative of a corrupt system that completely ignores the fears of the German public[7]. This leads to the ongoing polarisation of society, symbolised by demonstrations held by supporters and opponents of the plan to take in migrants, during which both sides had the same slogan on their banners: Wir sind das Volk (We are the nation)[8].

The AfD’s very presence in the Bundestag has limited Angela Merkel’s room for manoeuvre, and the Chancellor has been forced to negotiate a three-party coalition. In parliament, the AfD, as the third biggest political force, is able to influence the German public debate and build up its institutional position. Aside from the office of vice-president of the Bundestag and the posts of the heads of parliamentary committees, the AfD faction will receive around €16 million annually to carry out its activities. In connection with the almost 6 million votes it garnered in the elections, it will also receive state subsidies (from 83 euro-cents to 1 euro for each vote). The AfD is also hoping to get a portion of the €450 million sum which Germany earmarks each year for funding the activities of political foundations. The AfD will also likely receive several extra-parliamentary offices; for example, representatives of the Bundestag sit on the management board of the KfW development bank, and on the supervisory boards of Deutsche Welle and state-controlled TV stations.

The AfD will be an uncompromising opposition party. During voting night, Alexander Gauland, one of the leaders of its election campaign, announced that they would “hunt Merkel”. The party leaders will emphasise that, unlike the SPD, they are not entangled in the system, a narrative which will be favourable for the party, and boost its credibility. Looking at the AfD’s actions to date, one may conclude that the language of the public debate in Germany will become more aggressive, and the narratives offered by the AfD and the remaining parties will become increasingly divergent. It is already evident that in their attempts to prevent the AfD from spreading its influence at federal level, the remaining parties will resort to actions which are legal, yet infringe upon certain political traditions. For example, before the elections the Bundestag’s regulations were changed so that the representative of the right, Wilhelm von Gottberg, could not be elected president-senior of parliament and could not open the first session. After the elections, the candidacy of Albrecht Glaser, whom the AfD had nominated to the office of vice-president of the Bundestag, was blocked. An SPD deputy, Michelle Müntefering, launched an initiative to collect signatures from deputies to support a request to the council of senior parliamentarians to block the nomination of an AfD representative as head of the culture committee. The effectiveness of such actions is disputed, as it justifies the AfD’s theory of a conspiracy by the ‘old parties’ and the lack of ideology on the part of Christian Democrats. At the same time, it compromises the prestige of the state’s institutions.

The AfD’s presence in federal-level politics is no longer transitional. By now, the party has built a stable electorate and a strong intellectual power base[9]. In the Bundestag, the AfD group is characterised by the highest proportion of individuals holding a doctor’s or professor’s title. Across Germany, the party is closely affiliated to conservative academic societies (Burschenschaften). These elite male-only student societies, some of which have a history reaching back to 1815, and whose membership is frequently restricted only to ethnic Germans and Austrians, are a breeding ground for new members of the AfD[10]. Aside from swordsmanship and ritual games, members of these societies are involved in organising education and childcare activities for fellow members, with special emphasis on knowledge of history, patriotism, and readiness to serve their homeland.

The ideological rift

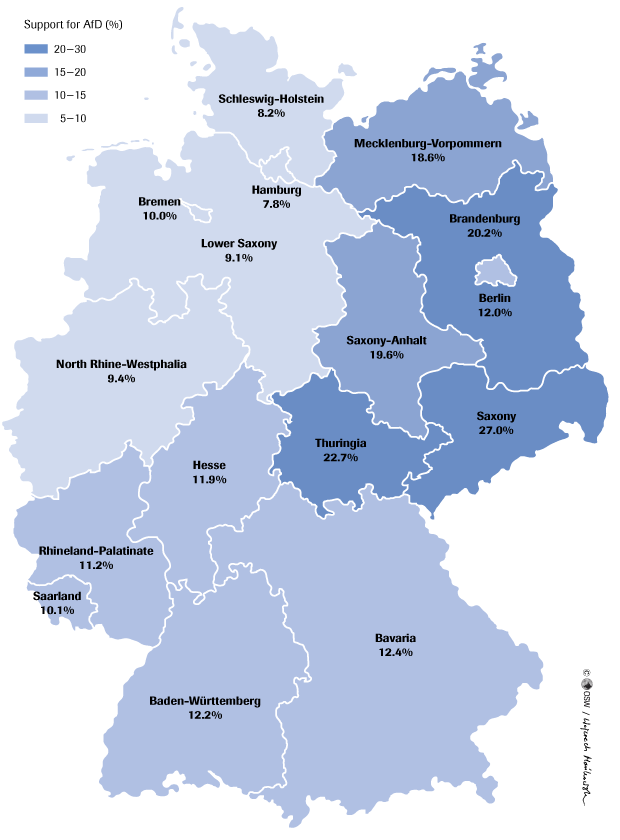

The elections to the Bundestag have shown that to some degree the ideological divisions in Germany overlap the regional divisions. Above all, an analysis of the election results reveals a long-standing division into east and west. In four (out of five) states of the former GDR, the AfD came second (in Brandenburg, Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; in one state it was the victor (in Saxony). This suggests that the anti-immigrant slogans and the rhetoric centred on ethnicity met with a favourable response in this part of the country in particular. But not only there: similarly, support for the AfD was relatively high (although not that high) in the southern part of Germany. In Bavaria as a whole, the AfD came third (with 12.4% of the votes, losing to the SPD by just 2.9%), but in 17 out of 46 constituencies it came first and the SPD came second. In Baden-Wurttemberg, the AfD scored its second highest result in western Germany (12.2%). In northern states, the support for the AfD was less than 10%.

This distribution of votes indicates that the support for radical right-wing parties does not, as it has been assumed for years, result from the feeling of being less affluent than the remaining part of ‘rich’ Germany. Bavaria and Baden-Wurttemberg are Germany’s second and third most affluent states respectively, and 73% of AfD voters assess their financial situation as good. By voting for the AfD, they intend to express their objection (85%) to the erosion of German culture, and to the far-reaching social changes caused by immigration and the excessive influence of Islam[11]. This is confirmed in a report summing up research conducted by the Bertelsmann Foundation, which suggests that the traditional establishment parties have not only lost those voters who have right-wing views, but also are affected by a massive outflow of urban voters who support the political centre. The voting choices made by the members of this group are increasingly less influenced by their profession and religion[12]. The AfD’s presence in the Bundestag results from the emergence of a division line which determines one’s attitude towards the nation, history, the state and culture. In the present parliamentary term, we will witness an ideological fight which will be transmitted by the national TV stations. As a consequence, the public mood is likely to become increasingly heated and polarised. Taking account of the fact that political opponents in Germany are inclined to use increasingly aggressive language, and to move their disputes to the streets (for example the protests against the G20 summit in Hamburg, the attacks on refugee centres), Germany will need to tackle the growing radicalisation of representatives of both the left and right wings of the political scene.

The percentage of votes cast for the AfD in specific federal states during the elections to the Bundestag. 24 September 2017

Source: https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/bundestagswahlen/2017/ergebnisse.html

[1] Aussagen zu den Parteien, https://wahl.tagesschau.de/wahlen/2017-09-24-BT-DE/umfrage-aussagen.shtml

[2] Wählerschaft der Parteien, DIW, 19 July 2017. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.562050.de/17-29.pdf

[3] Or that it is predestined to govern Bavaria on its own.

[4] Konservativer Flügel fordert neuen CDU-Chef, Die Welt, 26 September 2017, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article169059522/Konservativer-Fluegel-fordert-neuen-CDU-Chef.html

[5] ‘Darum muss Merkel den rechten CDU-Rand nicht fürchten’, 2 October 2017, http://www.rp-online.de/politik/deutschland/union-darum-muss-angela-merkel-den-rechten-cdu-rand-nicht-fuerchten-aid-1.7119585

[6] The SPD’s treasurer Dietmar Nietan said that due to the party’s poorest electoral result in its history, which will translate into lower state subsidies, the Social Democrats’ budget will record a deficit of around €1 million. Therefore, it is being suggested that the number of events organised by the SPD be reduced, and aid offered to party organisations in locations where the party scores very few votes be cut.

[7] This has become particularly evident during the migrant crisis. See A. Kwiatkowska-Drożdż, ‘Filozof patrzy na kryzys migracyjny‘, Tygodnik Powszechny, 14 May 2016.

[8] This is a reference to the slogan used in demonstrations held in the GDR from September 1989, during which the participants shouted ‘Wir sind das Volk’ (We are the nation) and demanded political reforms.

[9] Research conducted in a socio-economic panel (SOEP) to measure long-term loyalty towards specific parties shows, among other things, that the AfD has managed to build a stable electorate of 5–6% (i.e. comparable to the average approval ratings of the FDP over many years, and much higher than the level of support for neo-Nazi parties such as the NPD or the DVU). For more see A. Ciechanowicz, ‘AfD – the alternative for whom?,’ OSW Commentary, 10 February 2017, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2017-02-10/afd-alternative-whom

[10] See ‘Leitmotive der Deutschen Burschenschaft’, http://www.burschenschaft.de/fileadmin/user_upload/DB_Grundsatzbroschuere-LANGTEXTE-KA3__08.01.15.pdf; ‘Wie radikale Burschenschaften zur Kaderschmiede der AfD werden’, 27 July 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.de/2017/07/27/burschenschaften-afd-_n_17597626.html

[11] A poll regarding the biggest threats Germany needs to tackle according to AfD voters: Bundestagswahl 2017. Umfragen zur AfD, 24 September 2017, https://wahl.tagesschau.de/wahlen/2017-09-24-BT-DE/charts/umfrage-afd/chart_208795.shtml

[12] The authors of the report symbolically divide this group of voters into supporters and opponents of ‘modernisation’. For the enthusiasts of ‘progress’ the key words are: the environment, openness, multiculturalism, humanity. The opponents emphasise the value of tradition, nation and German culture. R. Vehrkamp, K. Wegschaider, Populaere Wahlen. Mobilisierung und Gegenmobilisierung der sozialen Milieus bei der Bundestagswahl 2017,6.20.2017. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/ZD_Populaere_Wahlen_Bundestagswahl_2017_01.pdf