Serving politics. Television’s role in Ukraine’s presidential election

Television plays a major role in the formation of public opinion in Ukraine. For 85% of the population, it represents their main source of information. By providing information about candidates in an election, their manifestos, and events surrounding election campaigns, television stations have a fundamental impact on the popularity of individual politicians and political parties, and their prospects of taking up senior posts. Online and press sources play a much smaller role in determining public opinion.

Although the authorities in Kyiv have attempted to legislate to reform the media sector from 2014 onwards, the process of making the envisaged changes has come to a standstill. It has proven impossible to eliminate the problems that existed in the media prior to the Maidan revolution. The major television stations are still controlled by a small group of the wealthiest oligarchs, and are used by these oligarchs as vehicles for furthering their business and political agendas. The predominantly privately-owned media are highly dependent on the political and business relations between their proprietors and politicians. As a result of these ties, television stations under oligarch control have been engaging in measures to support or discredit particular candidates in the current presidential election campaign. Due to the importance and the part played by the media in shaping public attitudes, their influence over the outcome of the presidential election due to be held on 31 March will be considerable.

A change that did not come to pass

Following the Maidan revolution, the expectations of Ukrainians that the situation in the country would improve went beyond those related to social and political changes, measures to combat corruption, and integration with structures in the West. They also related to reform of the media sector to improve freedom of speech[1]. There was a general expectation of greater media pluralism and objectivity, which has largely been eroded under Viktor Yanukovych’s rule[2]. The media were supposed to rein in the authorities and report faithfully on the domestic situation.

Under pressure from the public, the new government in Kyiv attempted to pass legislation in line with these public expectations. As early as April 2014, an act was passed to create a state-run broadcasting service based on the existing nationwide and local television and radio stations. This state broadcasting service was tasked with creating a medium to make programmes in the public interest[3]. In September 2015, parliament passed an act making it compulsory for radio and television stations to make public their ownership structure in full. This was done to guarantee transparency within the media sector and to prevent attempts on the part of business and political groups to monopolise it. In addition, 760 press publications that were under state and municipal ownership were privatised.

The media in Ukraine are highly dependent on the political and business relations between their proprietors and politicians.

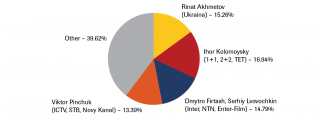

Despite this progress, the intended reform programme has come to a halt. The main media outlets, among them the top ten television stations, which have an audience of more than 60% of the media sector, are still controlled by a handful of the most powerful oligarchs: Ihor Kolomoysky, Rinat Akhmetov, Dmytro Firtash, Serhiy Lyovochkin, and Viktor Pinchuk (this share is even greater when the sport, lifestyle and children’s channels are included). By tightly controlling the editorial policy of television stations and the press, they support or oppose particular leaders and political forces, depending on how the relationship stands at the time[4]. As a result, the media, subjected to oligarchical interests, are not an adequate outlet for communication between the government and the public. Information is conveyed selectively and manipulated.

Although the oligarch-controlled television stations are not the oligarchs’ most important business assets, they serve as a form of political investment. In most cases, due to enormous financial outlays, these media, which are comparable to (or even exceeding) their Western counterparts in terms of technology, do not generate revenue. Due to support from specific political forces, however, the owners of the largest media concerns can balance the investment outlays with measurable benefits for their business operations in the form of legislation or political decisions favourable to their business. These ties mean that the owners use their television stations to further short-term interests at the expense of credible reporting. As a result of this dependence, the value of television stations is determined not only according to their position in the media sector, but also according to their ability to shape the image of politicians and political parties.

The political and business climate in which the mass media operate has led to various kinds of breaches of media freedom and journalistic standards. To achieve political and business goals, the owners of the largest media concerns keep the journalists working for them in line using a range of measures, including proprietor censorship in the form of financial or administrative penalties. It is common for politicians to order and pay for material that presents a particular person or event in a specific light (jeansa). As the presidential election draws near, this pathological situation in the media sector is worsening, causing the amount of paid material aimed at promoting particular politicians (parket) or discrediting them (chornukha) to increase.

Stars of television stations

More than 85% of the population of Ukraine say that they find out about the domestic situation and the world at large from television news programmes[5]. The role that television plays in forming the views of the public is also demonstrated by the high level of trust in the credibility of the information provided (61% of Ukrainians consider the output of nationwide television stations to be credible[6]) and the role it plays in moulding the public’s image of politicians (70% of respondents obtain information about election manifestos from television stations[7]).

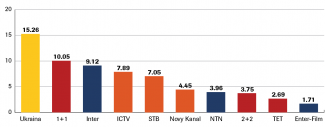

The television station with the highest viewing figures is Ukraina, which is controlled by the wealthiest Ukrainian, Rinat Akhmetov (15.26% of airtime in 2018)[8]. Ukraina is also in first place in terms of the volume of material that violates journalistic standards for current affairs reporting. It was responsible for almost 40% of all biased and unreliable material broadcast on Ukrainian television in 2018)[9]. The person most featured in hidden advertising is Oleh Lyashko, leader of the Radical Party, which the oligarch finances. In return, Radical Party MPs vote in parliament in line with his interests (particularly in relation to legislation concerning mining and metals, which is the same sphere in which Akhmetov’s Metinwest Group operates[10]). Lyashko is regularly featured as a guest on news programmes commenting on current affairs, and as a guest on programmes about social and commercial issues as well.

Another person who frequently appears on Ukraina is Oleksandr Vilkul, who is running for president as a member of the Opposition Bloc that is also supported by the oligarch.

Television plays a major role in the formation of public opinion in Ukraine and is the main source of information for the public.

An analysis of the content of news broadcasts on Akhmetov’s station shows that President Petro Poroshenko is presented neutrally (58.8% of cases) or favourably (41.2%)[11]. The sympathy that the oligarch has for the president, who is seeking re-election, takes the form of a series of exclusive interviews with Poroshenko, conducted since the beginning of the year (in the past, the president’s wife was a presenter of the station’s morning gymnastics show). The favourable stance of Akhmetov’s media is provided in return for the president’s administration assenting to the businessmen’s increasing influence, among other things, in the energy sector[12]. Providing media backing for as many as three presidential candidates is a form of investment for the oligarch, for whom this is a means of expanding his political influence.

The second most popular station is 1+1 (10,05% of the market), owned by Ihor Kolomoysky (2+2 and TET are also among the oligarch’s top stations). This station devotes an unusual amount of airtime to popular comedian Volodymyr Zelenskiy, who announced at the end of 2018 that he would be running in the presidential election, and currently leads in the election polls[13]. Zelenskiy appears not only in the weekly comedy show “95 Quarter” and the series “Servant of the People”, in which he plays the lead role, but also in a reality show that tracks how his election campaign is proceeding. A large portion of his satirical performances, and the news broadcasts, clearly adopt a negative tone towards President Poroshenko. The extremely negative image of the Ukrainian head of state portrayed on 1+1 is due to a severe conflict between President Poroshenko and the station’s owner.

In third place in terms of airtime is Inter (9.12% of the market), which is owned by oligarchs Dmytro Firtash and Serhiy Lyovochkin (NTN and Enter-Film also have high viewing figures), who hail from the camp of former President Viktor Yanukovych. This station is not far behind Ukraina with regard to the amount of hidden advertising (38% of all broadcasts of this type in 2018). The undisputed star of the Inter news bulletins is the long-term business and political partner of the outlet’s owners, Yuriy Boyko. Both the Opposition Platform – For Live presidential candidate, and the station that promotes him, are associated with a pro-Russian and anti-Western stance (in August 2018 the National Television and Radio Council fined the station for propagating Russian propaganda). Inter is another station that does not describe Poroshenko’s actions in a particularly critical light, leading to speculation that an agreement has been reached to exonerate Yuriy Boyko in a case concerning fraudulently obtaining state funds to purchase drilling rigs in 2011.

In fourth, fifth, and sixth place in terms of popularity are the television stations owned by Viktor Pinchuk and his wife Olena: ICTV (7.89% market share), STB (7.05% market share) and Novy Kanal (4.45% market share). Unlike the other oligarch-owned stations, Pinchuk’s stations present the most objective and evenly balanced picture of political affairs in the country, and are not biased towards any of the candidates in the presidential race. This approach corresponds to the oligarch himself, who tries to stay out of the limelight when it comes to current affairs, and avoids being associated with any political grouping, concentrating on trouble-free relationships with the other actors on the political and business scene in Ukraine.

Support given in the media to presidential candidates represents a form of investment for oligarchs, who use it to try to increase their political influence.

Other stations whose activities are dictated by the political activities of their proprietors have much less reach and significance in the media sector. Two of these stand out in particular: 112 (viewership share of approximately 1.5%) and NewsOne (share of approximately 0.7%), which have been owned for just a few months by Taras Kozak, a close partner of Viktor Medvedchuk and one of the main lobbyists for Russian interests in Ukraine. Some programmes broadcast by these stations prompted parliament to adopt a resolution calling upon the National Security and Defence Council to impose penalties for promulgating pro-Russian propaganda. Channel 24, owned by the wife of presidential candidate Andriy Sadovyi, and Channel 5, which is under the control of Petro Poroshenko, are less controversial. Both of these stations are “faithful” to their principals, promoting their candidature and manifestos.

Further down in the rankings of TV station popularity, with just 0.5% of airtime, is the only state-run television channel, UA: Pershyi. The importance of this station among viewers is symbolic of the state of reform of the state media in Ukraine. The founding in 2014 of a joint-stock company on the basis of the state broadcaster at the time was intended to represent a transformation of the state-run nationwide and local television and radio stations into state-run media, whose mission was to report on the country’s political, social, and cultural affairs accurately and objectively. This outlet, funded by the state but at the same time independent of the political climate, was not well received by politicians. Despite a main television station and local versions of the station being launched, decision-makers did not provide even half of the funds designated for the broadcaster, rendering its activities highly circumscribed.

The online media and press play a much smaller role in shaping public opinion than TV stations.

Ultimately, the supervisory board dismissed the company’s director, Zurab Alasania, at the end of January 2019. Some of the journalist community consider the dismissal of this valued journalist and manager to be linked to the ongoing election campaign and the station’s independent editorial policy under his direction. Despite the station not having extensive reach, the investigative journalism programmes created by its team, on the subject of corruption at the highest levels of government, turned out to be very popular online, which must have displeased many high-ranking officials.

The fate of the station Hromadske is also not unusual. This station, launched on the day before the beginning of the Maidan revolution, was an example of a grass-roots social initiative inspiring hope for a new level of quality in the media. Meanwhile, internal conflicts and reliance on external funding in the form of international grants caused the outlet to become marginalised on the media scene. Other projects of this kind met a similar fate, such as Espreso.tv, created by politician and journalist Mykola Kniazhytsky, and, for example, Spilno.tv, which no longer exists and was operated by Maidan activists.

TV for which there is no alternative

The online media and the press play a much smaller role in forming the public mood than television stations. Only 27.1% of Ukrainians say that they get their news from online media, while 8.1% say that they obtain it from newspapers and magazines. At the same time, the number of people using online sources is increasing, and the number of people consulting the press is waning (subscriptions to newspapers have gone down by as much as 27% over the last three years)[14].

Betrayal of journalistic standards and ethics in the online media and press is also a serious problem. Experts at the Kyiv Mass Information Institute say that the amount of political advertising ordered and paid for in the form of articles published online in September 2018 reached the highest level for five years. The largest amount of this material was found on the websites UNIAN (owned by Ihor Kolomoysky) and Obozrewatel (registered to the sons of Mikhailo Brodsky, a former business partner of Ihor Kolomoysky).

Over the last two years, texts published online and in the press that were ordered and paid for concerned the Ukraine Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate (an average of 9.7 texts produced to order per week), the Opposition Bloc and the Revival Party (7.7), the Radical Party and its leader Oleh Lyashko (5.5), Yulia Tymoshenko and Vadym Rabinovych (3.8 each), and Viktor Medvedchuk (3.1). The most trustworthy and accurate online sources were found to be “Ukrayinska Pravda, “Ukrinform” and “Liga”[15].

Closed arrangement

The specific manner in which television functions in Ukraine is a result of the oligarchical system, which has not changed fundamentally in spite of Maidan revolution. The politicisation of the Ukrainian media, the breaches of journalistic standards, and the increasing amount of hidden advertising is due to media capital being concentrated in the hands of the business elite. For this elite, TV stations are not any ordinary business, but a means of achieving political ends. This is demonstrated by the fact that for many years Ukraine has come below 100th place in the ranking of countries according to freedom of the press, and by the slow rate of progress in addressing this problem (an improvement from 126th place in 2013 to 101st place in 2018)[16].

By manipulating the public, skirting over subjects that are troublesome for the politicians being supported, and launching campaigns to discredit people who are bothersome and protected by oligarchs, the media have a substantial influence over the popularity of politicians and political parties, and upon public opinion. The success of election campaigns of particular politicians depends on the support they are given by the most popular media outlets owned by the oligarchs.

The specific manner in which television functions in Ukraine is a result of the entrenched nature of the oligarchical system.

As the media market becomes more rigid, activists and politicians who are not part of the political and business establishment become marginalised in public debate and cannot effectively convey their message to the public without the appropriate financial and media backing. This prevents lesser known politicians and politicians who are not connected with the narrow political and business elite in Ukraine from taking part in the political process. The fact that communication is dominated by a media owned by the wealthiest and most powerful people in the country significantly limits political pluralism. As a result, the television market is structured in a way that greatly obstructs democratisation of the country and the carrying out of reform.

owned by particular oligarchs

Data for: Industrial Television Committee (Індустріальний Телевізійний Комітет)

[1] Petro Poroshenko pledged to reform the media sector and strengthen the role of the media as a means of reining in the government in his election manifesto in May 2014: https://programaporoshenka.com/Programa_Poroshenko.pdf

[2] T. Iwański, ‘The press and freedom of speech in Ukraine ahead of parliamentary elections’, OSW Commentary, 24.09.2012, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2012-09-24/press-and-freedomspeech-ukraine-ahead-parliamentary-elections

[3] ’Про Суспільне телебачення і радіомовлення України’, https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1227-18

[4] Д. Дуцик, А. Мніх, П. Бурковський, ‘Основні тенденції медіависвітлення суспільно-політичних процесів в Україні у 2014-2017 рр.’, Kyiv 2017, p. 7–17, https://ms.detector.media/content/files/dm_news_2014-17_internet.compressed.pdf

[5] Протидія російській пропаганді та медіаграмотність: результати всеукраїнського опитування громадської думки. Аналітичний звіт, Детектор медіа, Kyiv 2018, p. 10, https://detector.media/doc/images/news/archive/2016/136017/DM_KMIS_ukr__WEB-2.pdf

[6] ‘Ставлення населення до ЗМІ та споживання різних типів ЗМІ у 2018 року’, Internews, Kyiv 2018, p. 5, https://internews.in.ua/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2018-MCS_FULL_UKR.pdf

[7] ‘В очікуванні президентських виборів: настрої українців, Рейтинг’, 26.06.2018, http://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/v_ozhidanii_prezidentskih_vyborov_nastroeniya_ukraincev.html

[8] ‘«Україна» стала лідером телеперегляду у 2018 році, друге місце – в «1+1», ICTV та «Інтера»’, Детектор медіа, 8.01.2019, https://detector.media/rinok/article/143867/2019-01-08-ukraina-stala-liderom-telepereglyadu-u-2018-rotsi-druge-mistse-v-11-ictv-ta-intera/

[9] З. Красовська, ‘Кого найбільше піарили в теленовинах 2018 року’, 25.01.2019, Детектор медіа. https://ms.detector.media/monitoring/daily_news/kogo_naybilshe_piarili_v_telenovinakh_2018_roku/.

[10] А. Кривко, ‘Депутати за викликом. Як “радикали” Ляшка Ахметову допомагають’, Українська правда, 24.05.2018, https://vybory.pravda.com.ua/files/graph/deputaty_za_vyklykom/

[11] В. Кондратова, ‘Говорит и показывает кандидат. Кому помогают телеканалы олигархов’, ЛІГА.net, 7.12.2018, https://www.liga.net/politics/articles/govorit-i-pokazyvaet-kandidat-komu-pomogayut-telekanaly-oligarhov

[12] Introduction of the Rotterdam+ formula when calculating the price of coal purchased by the state from the oligarch’s companies significantly increased their revenue, see T. Iwański, ‘Prywatyzacja po ukraińsku: Achmetow umacnia się w energetyce’, Analizy OSW, 6.09.2017, https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/analizy/2017-09-06/prywatyzacja-po-ukrainsku-achmetow-umacnia-sie-w-energetyce

[13] K. Nieczypor, ‘Od “sługi narodu” do trybuna ludowego? Wołodymyr Zełenski w wyborach na prezydenta Ukrainy’, Nowa Europa Wschodnia, 24.01.2019, http://new.org.pl/5933-od-slugi-narodu-do-trybuna-ludowego-wolodymyr-zelenski-w-wyborach-na-prezydenta-ukrainy

[14] ‘За три роки передплата газет і журналів скоротилася майже на третину’, Укрінформ, 7.08.2019, https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-regions/2512974-za-tri-roki-peredplata-gazet-i-zurnaliv-skorotilasa-majze-na-tretinu.html

[15] ‘Саморегуляція та журналістські стандарти під час виборчих кампаній’, Укрінформ, 17.09.2018, https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-presshall/2532146-samoregulacia-ta-zurnalistski-standarti-pid-cas-viborcih-kampanij.html

[16] , 2018 World Press Freedom Index, Reporters without Borders, https://rsf.org/en/ukraine