To serve the people – total power in Zelensky’s hands

The key slogans of the campaign of Volodymyr Zelensky and his party Servant of the People ahead of the presidential and parliamentary elections were: to bring fresh blood into the political class and to introduce honest professionals to politics who have not been discredited. The new president had no political experience whatsoever and, as a result of the parliamentary election, over three quarters of the seats in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian parliament) will be taken by individuals who have never served as members of parliament. The new parliament will have the lowest average age of its deputies since 1991 and the largest proportion of women (around 20%). The largest number of new and young politicians has been introduced to the Verkhovna Rada by the Servant of the People party and the Voice party.

The sweeping victory attained by Zelensky’s party will allow it to form a government by itself. The president has announced that a new prime minister will be an economist “without political experience”, and it can be assumed that this principle will also apply during the selection of most of the new ministers. Thus Ukraine, being at war with Russia and struggling with low economic growth, will be governed by individuals who are new to politics. This situation, being an effect of the high hopes and expectations of the Ukrainian public for a fundamental change of the system, is giving rise to the significant potential for positive changes but also might put the political stability and further development of the Ukrainian state at risk.

The sources of success of the Servant of the People

The success of Zelensky and the Servant of the People is above all an effect of the promise to remove old politicians and thoroughly reorganise the state through the engagement of non-discredited professionals. This coincided with the radical rejection by the voters of the team which governed Ukraine during the past five years and with the lack of improvement in the politico-economic situation. The political establishment has been disliked in Ukraine for many years, which was strongly emphasised during the Revolution of Dignity. However, five years ago, when the Ukrainian economy was plunged in a deep crisis, Crimea was annexed by Russia and the Donbass was the scene of intensive military operations with the participation of regular Russian army troops, Ukrainians elected politicians who were widely associated with experience, stability and the ability to cope with external aggression. This led to victory for the pro-Western oligarch Petro Poroshenko in the presidential race and the parliamentary success of the People’s Front, a party which had been hastily formed by economists, volunteers, military officers but also by numerous professional politicians who treated their parliamentary seats as a guarantee of success in business.

In 2019, the Ukrainian public grew accustomed to the war in Donbass, especially since it is low in intensity and the peace talks have been deadlocked. In turn, the economic situation has stabilised to such an extent that Ukrainians are thinking not so much about survival but also about development. The growing aspirations and the diminishing sense of threat have made the public more sensitive to corruption and many other pathologies in which the post-Maidan government was involved. The Ukrainian public started to believe that the only chance for improving their life and modernising the state will be to give power to people from outside the system who share the fears and

The fact that the party is strongly identified with the president means responsibility for the political processes in the country will predominantly be put on Zelensky.

hopes of most of the Ukrainian public, and not to corrupt politicians who have no idea about everyday reality, who have connections with oligarchs and failed to implement the promised reforms. Zelensky and the people linked to him understood this well and responded to this demand which led to electoral defeat for the previous government. While in 2014 the People’s Front garnered 22% of the votes, the Petro Poroshenko Bloc 21% and Self Reliance 11%, in July 2019, the People’s Front received 0% and was not even taken into account in the last polls. The Petro Poroshenko Bloc rebranded itself as “European Solidarity” and received 8.5%And Self Reliance received 0.6%. Therefore, it seems reasonable to go along with the thesis that by ridding themselves of the old politicians, in 2019 Ukrainians implemented another stage of the Revolution of Dignity or launched another revolution, this time an electoral one[1]. They preferred to take the risk of entrusting power to anyone trustworthy (according to a survey conducted in July, 60% of voters have declared they trust Zelensky) who promised to bring new faces into politics, rather than once again cast their votes for representatives of the disgraced establishment.

New is coming

The parliamentary election was unprecedented in several aspects. Never before did a victorious party garner such a high level of public support (around 43%) and gain such a large representation in parliament (254 MPs). What decided about the scale of Zelensky’s victory was the surprisingly good result achieved in single-member constituencies (130 seats), regardless of the fact that according to the estimates ahead of the election, representatives of Servant of the People were predicted to win around 80 of them. None of the deputies from this party has ever been a member of parliament; this is an effect of the criterion adopted while preparing the election lists and selecting candidates in single-member constituencies. At the same time, this condition, which was also applied in the party lists of the Voice, practically eliminated the chances of victory for most of the representatives of the inter-party faction of Euro-optimists consisting of 25 members who made efforts to push through reforms in the previous parliament.

Zelensky’s popularity, being the main source of the success of his party, meant that many seasoned MPs lost the struggle for a seat in the new Verkhovna Rada. Another aspect of this victory is also the fact that some oligarchs’ influence in parliament has weakened. This in particular concerns Rinat Akhmetov. However, it is still unclear how strong an impact another oligarch, Ihor Kolomoyskyi who strongly backed Zelensky during the presidential race, will have on Ukraine’s political life. It is estimated that he may control dozens of deputies, but it is only future nominations in the government and state-controlled companies that will show the real scope of his influence. A conflict between Kolomoyskyi and Zelensky seems to be just a matter of time, considering the oligarch’s ambitions. It is still an open question what the scale and the character of the conflict will be.

Zelensky’s huge success during the presidential election and the subsequent sweeping victory of the Servant of the People in the parliamentary election prove that the party is strongly identified with the president. In practice this means that, as viewed by the public, Zelensky will be the main person responsible for the political processes in the country. However, the scope of his control over the party is currently unclear.

Hopes, risks and question marks

The sweeping victory and the total power attained by Zelensky gives rise to both hopes and risks. The main hope can be pinned on the effectiveness of the decision-making process. If the president’s party has a parliamentary majority and forms a government by itself, the traditional disputes within the triangle between the legislative and executive powers and the presidential administration will be less intense. However, it also seems that the president intends to carry out real changes in Ukraine. Therefore, to fulfil the expectations pinned on him, shortly after the inauguration of the new parliament, he will put forward a number of pro-modernisation legislative initiatives which will be passed smoothly. The most likely initiatives include an anti-corruption campaign, a continuation of the deregulation of the economy and laws curbing the impunity enjoyed by politicians (including the removal of parliamentary immunity and passing regulations on the president’s impeachment). At the same time, given the de facto monopoly of power, the checks and balances system will not work at full capacity, and it is presently unclear whether this potential will be utilised to conduct the reforms expected by the Ukrainian public or to appropriate the state.

The parliamentary groupings that are in opposition to the Servant of the People government are divided and have different political manifestos. Although it is possible to imagine them agreeing on stances on some issues (including with the government), a comprehensive and coordinated co-operation is ruled out. Even though most of the opposition parties have significant financial and media resources at their disposal (such as the European Solidarity, the Opposition Platform – For Life and Batkivshchyna), they will not be able to outweigh the potential of the Servant of the People which has state instruments at its disposal. A situation like this may tempt the most senior state authorities to abuse power and instrumentalise the law, which may even lead to a regression of democracy.

The total power held by Zelensky, given the weakness of the state institutions and the fragmentation of the opposition, may prove to be a temptation to those in power and lead to a regression of democracy.

However, the biggest question is how the Servant of the People grouping will function in parliament. The party was established shortly ahead of the election and presented people from various circles as its candidates, with different experience and competences. It is only after the final outcome of the election has been announced that the party leaders and the president will finally find out what potential they have at disposal. However, it is a fact that the new deputies do not form a coherent group sharing similar values or even interests. Given this diversity and also the large number of members, separate factions and interest groups are inevitably bound to be formed inside it. While it seems that some of these groups will be organised guided by personal loyalties (for example, a group linked to Kolomoyskyi, a group linked to the Kvartal 95 company, a group of professionals), there will be still a large group of deputies whose connections and motivations are unclear. They may become engaged in pro-reform initiatives in the broad meaning of the term, but it should be assumed that some of them will be tempted by corrupt offers. Thus, it is a great challenge for Zelensky to become capable of leading the faction and reducing conflicts of interest that may arise in the future.

Ukraine is heading to the unknown

It seems that, regardless of the extensive prerogatives both the new government and the parliament will have, the presidential administration will remain the centre of power. This will be an effect of the fact that deputies representing the Servant of the People to a great extent owe their parliamentary seats to Zelensky and the fact that this centre formed first and is currently making the most important staffing decisions. At the same time, since the president has no political experience, his advisors and aides introducing him to the government system will play a serious role. This system is particularly complex in Ukraine, given the multitude of informal business-political and family connections which are often more important than official party membership.

Inside Zelensky’s inner circle, the head of the Presidential Administration, Andriy Bohdan, will play the role of a ‘guide’. Mr Bohdan acted as an attorney of the oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyi and served as a deputy minister of Justice (2007–2010). He is a good lawyer who both knows well the rules of the state administration’s operation and has extensive contacts inside Ukraine’s political and business elite. Zelensky also reportedly trusts Bohdan because it was his idea to put forward the actor as a candidate in the presidential election. However, despite his young age (43) and considering his professional and political experience, he fits in well with the old order and will be more inclined to bend the law and use legal loopholes rather than improve the law as part of the system. Such a character of relations between the two politicians may enhance Bohdan’s ambitions and thus his influence on current politics.

The election in 2019 redefined the main axis of the political divide in Ukraine. While in 2014 it was organised by the dichotomy: pro-Western vs. pro-Russian, since then this dispute has more and more clearly been arranged along the line that divides the politicians into ‘old’ and ‘new’. At the same time, the term ‘old’ does not refer to age but rather to formal participation in the pathologies of Ukraine’s political life. Likewise the term ‘new’ is a synonym of high moral and professional standards and the absence of links with oligarchs and the corruption-stained past. The government constellation that has formed as a result of the presidential and parliamentary elections is formed predominantly by inexperienced individuals whose views concerning the key lines of the development of the state are unclear, and who will only begin to learn how to function in politics. Furthermore, they have gained total power, and the mechanisms of its control are weak. The composition of the new government, which will most likely be formed predominantly by professionals, gives some hope. Nevertheless, the election this year is bringing Ukraine to a new stage which will decide whether youth and a lack of experience are a good recipe for the modernisation of the state which is so much desired by the Ukrainian public.

Appendix

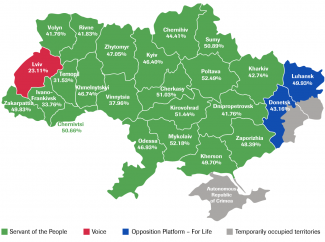

Map 1. Winners by oblasts of Ukraine from the national list

Source: Ukrainian Central Election Committe

Chart 1. Support levels for political parties which crossed the 5% election threshold

Source: Ukrainian Central Election Committe

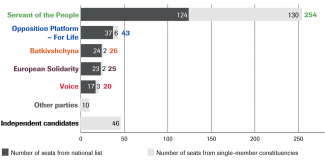

Chart 2. Number of seats won

Source: Ukrainian Central Election Committe