Tightening the screws. Putin’s repressive laws

In December 2020, President Vladimir Putin signed a package of laws tightening regulations on non-governmental organisations, public gatherings and media censorship. It is one of the elements marking a new quality in the Kremlin’s domestic policy: Russian authoritarianism has de facto abandoned the pretence of democratic procedures in favour of increased control and repression.

The laws reflect the unease of those in power, engendered by the pandemic, the economic crisis, growing public discontent and the waning influence of state propaganda on citizens. The authorities are primarily concerned about the course of parliamentary elections scheduled for September 2021. This fear has been fuelled by mass protests in Belarus, until recently considered a stable authoritarian regime. In addition to legal measures, the crackdown on political opponents has been reinforced by the neo-Soviet “besieged fortress” rhetoric, including warnings about alleged foreign interference in the elections. However, the strategy adopted by the Kremlin is likely to prove counterproductive and merely inflame the electorate further.

The objectives of the Kremlin’s legislative offensive

On 30 December, Putin signed a series of amended laws tightening the regulations governing several key areas of independent civic activity. The government’s prime targets are non-governmental organisations, independent activists, public gatherings and independent sources of information (see the Annex for detailed contents of the new laws).

Fighting “foreign agents”

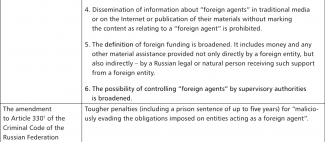

Prior to recent amendments, notorious Russian laws on “foreign agents” referred to “foreign-funded” non-governmental organisations engaged in “political activities” (the law adopted in 2012),[1] media outlets (since 2017)[2] and journalists and bloggers (since 2019).[3] From now on, two further categories of entities can be labeled with this status. The first one is individuals who “engage in politics in the interests of a foreign state or its citizens or a foreign organisation”. Individuals classified as “agents” will, for example, be barred from appointments to posts in the state and municipal administration (the authorities are also planning to de facto bar them from running for elected positions – see below). The second category are organisations which meet the criteria defined in the 2012 law on NGOs but – unlike NGOs – are not registered as legal persons (e.g. various types of associations, social movements etc.). Until now, this less formal type of activity has been one of the frequently used gateways to circumvent the restrictive provisions targeting “foreign agents”.

The above mentioned entities are required to register as “foreign agents” and report regularly to the Ministry of Justice on their activities and financial accounts, facing a much heavier workload than individuals and organisations outside this list. There are also virtually unlimited possibilities for harassment of “agents” by control and supervisory authorities.[4] The mass media, when publishing information on “foreign agents” or their materials, are obliged to always mention their “foreign agent” status.

At the same time, the definition and forms of “political activity” have been made more specific and the definition of “foreign funding” has been broadened.[5] The terms used in the legislation are very broad and may potentially include any public activity. The formal exclusion of activities in the areas of science, culture, health care, social assistance and environment from “political activity” is likely to be insignificant in light of the Kremlin’s clearly outlined course of suppressing independent circles. Health care or social assistance are potentially dangerous topics for the authorities in the context of the pandemic and environmental issues have been a frequent trigger for local protests in recent years.

Abolishing freedom of assembly

Although freedom of assembly, above all peaceful protest against the authorities, has long been increasingly restricted in Russia, loopholes have sometimes made it possible, if not to organise demonstrations effectively, then to successfully uphold legal rights in court. One such loophole was individual and collective pickets, requiring no approval from the authorities. The new legislation removes this loophole by broadening the definition of “public assembly”, expanding the array of elaborate requirements (including financial ones) as to how assemblies should be organised, making it easier for administrative authorities to ban or cancel them, and limiting the rights of journalists who cover the demonstrations. The legislation effectively abolishes freedom of assembly in Russia, and the organisation of any form of public protest will be subject to prior approval of officials and strictly regulated.

Stepping up Internet and media censorship

Further restrictions on providing information have been introduced to constrain independent media outlets. There is a legal means of blocking (or hampering the operation of) such sites as Facebook, Twitter or YouTube if they “discriminate” against Russian entities (in practice, this could involve situations where, for example, material distributed by Kremlin propagandists is removed as part of the fight against disinformation).

Penalties for “defamation” have been toughened, thus significantly expanding the scope to punish Internet users for criticising the authorities (the regulations also implicitly include accusations of corruption). Fines for “posting offensive content on the Internet” have also been increased several fold. The law was advertised as an act “against the rudeness of officials” (contemptuous remarks made by officials at various levels towards fellow citizens have caused public outrage in recent years), but its provisions are universal and the definition of an “offensive” remark by Internet users is wide-ranging.

A number of obligations related to control of content prohibited by law have been imposed on entities managing social media.[6] Considering the broad interpretations applied by law enforcement agencies in defining violations of the law, as well as the widespread use of such regulations against political opponents, this will likely serve as an additional tool for censoring information posted on the Internet. It is also designed to stifle grassroots activity (in recent years, social media have become the main channel for mobilising protest potential among citizens).

The new regulations also reinforce the protection of personal data of public officials, including their assets. The formal grounds for prohibiting data operators from disclosure of such information have been expanded. Moreover, the dissemination of information about operational and investigative activities by law enforcement bodies has been banned. The law appears to be primarily a reaction to leaks that have discredited the Russian secret services in recent years. It is intended to impede independent investigations into violations of the law by officials and representatives of the secret services and law enforcement bodies, including corruption offences and the use of violence against peaceful demonstrators. It is also meant to prevent the collection of data on secret service officers involved in operations in Russia and abroad aimed, for example, at eliminating individuals considered dangerous to the regime.

Restricting electoral competition

The parliament is also working to further restrict electoral competition, which has already been reduced to a minimum in Russia. Draft laws under consideration include the introduction of new concepts into the law – “a candidate in elections acting as a foreign agent” and “a candidate associated with a foreign agent” – as well as restrictions on online election campaigning.

These laws are not the only indication of qualitative changes in the evolution of the Russian authoritarian regime in 2020. A constitutional reform was carried out between January and July, definitively consolidating the regime and concentrating even more powers in the hands of Putin. The president was also given the right to remain in power until as late as 2036[7] (however, it is not clear whether he will exercise this right). Significantly, the reform was carried out in violation of the current constitution, and a national plebiscite to approve it was rigged on an unprecedented scale. The electoral law was also amended, providing further grounds for restricting political competition, as well as granting new tools to facilitate electoral fraud and hamper independent monitoring of the voting process.[8] The December laws are the final stage in the implementation of this strategy, which is intended – in the eyes of the rulers – to guarantee the stability of the system of power in the years to come.

The new rules as an expression of the Kremlin’s anxiety

The near simultaneous introduction and expedited adoption of so many amendments was designed to intimidate the Kremlin’s opponents and demonstrate the government’s strength in the face of uncertainty over the September 2021 parliamentary elections. Some deputies have explicitly linked the repressive legislation to election preparations. Although the Kremlin’s political scenarios for the coming years are unknown, it should be assumed that this year’s elections are meant to serve as a test of the system’s efficiency. Furthermore, a reconfigured parliament will have a role to play in stabilising the system before a possible change of the head of state – hence the absolute loyalty of deputies to the Kremlin is crucial.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has temporarily strengthened attitudes of passivity and attachment to paternalism in relations with the government within Russian society, and the economic downturn has turned out to be moderate (GDP declined by approximately 3.1% in 2020, according to official estimates), the fear of a possible political crisis is clearly growing among Kremlin decision-makers. This stems from an awareness of a gradually deepening public discontent with the policies of those in power, as well as adverse developments in the international situation (see below).

Since 2018, public support for the president has remained about 20% lower than in 2014–2017. In 2020, Putin’s electoral rating among the youth decreased almost twofold, from 36 to 20 percent[9] (which may foreshadow a similar downward trend in other age groups). Moreover, sociologists are noting a gradual increase in demand for change and in awareness of civil rights among Russians, as well as growing frustration with the dysfunctional state governance system. The economic crisis caused by COVID-19 has overlapped with the long-term effects of the 2015–2016 recession and exacerbated the structural problems of the economy (one of the most important consequences of this situation is a decline in real incomes of the population since 2014). Forecasts indicate that Russia will face long-term stagnation after the pandemic, with citizens’ incomes falling for the next few years. The strength of the Putinist system largely stems from a lack of alternatives to authoritarian power, which is a result of the weakness of the opposition, as well as the Kremlin’s relatively effective strategy aimed at marginalising it.

At the same time, state propaganda is becoming less effective, primarily due to a rapid growth of independent Internet sources. Despite the ambitions to “sovereignise” the Russian segment of the web[10] and censor the contents posted there, circulation of information online is still fairly free and citizens are increasingly reluctant to obtain it from Kremlin-controlled television. In August 2020, 81% identified the Internet and social media as sources of knowledge about the country and the world, and 54% said they trusted them. For television, the figures were 69% and 48% respectively. By comparison, in 2009, 94% of respondents obtained information from television (80% trusted it), 9% from the Internet.[11]

Repressive measures against the media have also had a limited effect. Mass media outlets included in the list of “media – foreign agents” under the 2017 law (such as Radio Svoboda) are still operating – despite organisational difficulties – and many more independent sources of information are being created (some of them are based abroad). Media outlets taken over by circles loyal to the Kremlin (such as Lenta.ru or Vedomosti) are being replaced by new online projects (Meduza, VTimes) which maintain previous editorial policies. The field of investigative journalism is also developing (e.g. The Insider, Proyekt). As a result, cases of corruption, abuse of power and violations of civil rights are more frequently and effectively publicised. Independent media initiatives are also increasingly raising funds through crowdfunding. Its importance is demonstrated, for example, by the case of the weekly New Times, fined 22.3 million rubles (then about $360,000) in 2018 for allegedly violating financial regulations. The required sum was collected among Internet users within four days.

When it comes to international developments, the mass protests in Belarus have made the Kremlin aware of the potential fragility of the authoritarian model of government, while Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential election means a possible weakening of Moscow’s international position (e.g. as a result of restored transatlantic cooperation). In the face of these challenges, and with no strategic vision for the country’s development, the authorities have adopted a two-pronged strategy. Firstly, they are tightening regulations aimed at Russian civil society, having recognised that the existing legal instruments are insufficient to maintain political stability. Secondly, they are trying to mobilise the electorate by reinforcing the “besieged fortress” narrative and warning against foreign interference in the elections. This strategy is also intended to create a fait accompli in relations with the new US administration, which has stated its commitment to defending human rights in the international arena.

A new stage in Russian authoritarianism

The contents of the laws amended in December 2020 indicate that they are intended to make it easier for the authorities to crack down on civic activity, particularly those forms which could affect the course of elections (such as reaching out to the electorate with information about independent candidates, organising election monitoring or instigating protests against fraud).

The Kremlin’s actions mark the beginning of a qualitatively new stage in the evolution of Putin’s regime. The contours of the legal regulations adopted in 2020 indicate that it has abandoned any semblance of legalism (this is primarily evidenced by how the constitutional reform proceeded) and attempts to imitate democratic procedures (a number of rights and freedoms enshrined in the constitution, such as freedom of speech or assembly, have ultimately become fiction). Russia is thus moving towards an openly dictatorial model of government and the Kremlin is displaying an ambition to introduce elements of a totalitarian state into its relations with society. The authorities are increasingly interfering in previously unregulated areas of public and even private life. The sheer number of often overlapping prohibitions and orders is intended to intimidate citizens and force them into inaction and self-censorship. Both the rhetoric of the ruling elite (e.g. pointing to the “foreign agents” as alleged “enemies”) and the substance of the new regulations indicate that any civic activity deemed by the authorities to be a demonstration of disloyalty to the system, especially among the opposition, can potentially be treated as an anti-state crime. Those forms of activity which offer a chance to overcome the atomisation of society inherited from the Soviet Union, one of the pillars of the current regime, are seen by the Kremlin as the primary threat.

However, given the information environment in which Russians operate, control and repression as the basic methods of governance will become increasingly ineffective and costly. The strategy designed to “petrify” the political sphere before the parliamentary elections may prove counterproductive, and even whip up the mood of protest, especially if the pre-election period reveals any indications of social frustration, caused by the mistakes and negligence of the authorities in the fight against the pandemic.

APPENDIX. Repressive legal acts signed by Vladimir Putin on 30 December 2020

[1] More: K. Chawryło, M. Domańska, ‘Strangers among us. Non-governmental organisations in Russia’, OSW Commentary, no. 184, 28 September 2015, www.osw.waw.pl.

[2] M. Domańska, ‘Rosja: cios w zagraniczne media’ [‘Russia: a blow against foreign media’], OSW, 16 November 2017, www.osw.waw.pl.

[3] M. Domańska, ‘Rosja: zacieśnianie kontroli nad niezależnymi źródłami informacji’ [‘Russia: tightening control over independent sources of information’], OSW, 22 November 2019, www.osw.waw.pl. In December 2020, five individuals – human rights defenders and journalists – were included in the Justice Ministry's list of “foreign agents”, alongside twelve media outlets. The official list can be found on the website of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation, www.minjust.gov.ru.

[4] A person on the list of “agents” is, for instance, required to complete an 85-page form once a quarter.

[5] Foreign funding can occur without the will and prior knowledge of the relevant entity, which has no means of verifying the nationality of donors. The regulations also do not specify the minimum amount of such support. The “League of Voters” foundation was put on the list of “agents” after 225 rubles ($3) were transferred to its account by a Moldovan citizen.

[6] The amendment thus expands the regulations adopted in March 2019 that impose similar obligations on the mass media. See M. Domańska, J. Rogoża, ‘Russia: stricter Internet censorship’, OSW, 13 March 2019, www.osw.waw.pl.

[7] More: M. Domańska, ‘“Everlasting Putin” and the reform of the Russian Constitution’, OSW Commentary, no. 322, 20 March 2020, www.osw.waw.pl.

[8] Details: M. Domańska, ‘Pandemiczna nowelizacja prawa wyborczego w Rosji’ [‘The pandemic amendment of the electoral law in Russia’], OSW, 27 May 2020, www.osw.waw.pl.

[9] А. Корня, ‘«Левада-центр»: рейтинг Владимира Путина среди молодежи упал почти в два раза’, Открытые медиа, 10 December 2020, www.openmedia.io.

[10] More on the “sovereign” Internet law (fully entered into force on 1 January 2021): M. Domańska, ‘Gagging Runet, silencing society. ’Sovereign’ Internet in the Kremlin’s political strategy’, OSW Commentary, no. 313, 4 December 2019, www.osw.waw.pl.

[11] Data from the independent Levada Center: ‘Четверть Россиян потеряли доверие к телевидению за десять лет’, 1 August 2019, www.levada.ru.