Germany and the trade conflict between Lithuania & China

The Chinese government’s trade boycott of Lithuania risks causing economic losses for Germany and weakening the cohesion of the EU’s common market. However, Berlin is unlikely to take any decisive actions – such as pushing through retaliation – due to its huge dependence on the Chinese market, as well as differences of opinion within the government on what direction its Beijing policy should tale. Thus Germany will limit itself to diplomatic efforts, counting that the actions taken at the EU level by the European Commission and the French presidency of the EU Council will be effective.

In December 2021, the political dispute between Lithuania and China, which had been escalating for many months, took a turn for the worse. In response to Taiwan – and not just Taipei, as in other countries – opening a representative office in Vilnius, Beijing decided to impose informal restrictions on its trade with Lithuania. The country was removed from the Chinese Commercial Register, a move which makes customs clearance impossible (see ‘A new phase of China's pressure on Lithuania: weaponisation of European value chains’). The current dispute is the culmination of a series of events over the last few months: Vilnius’s increased criticism of human rights violations in the PRC, Lithuania abandoning the 17+1 format for Beijing’s cooperation with Central and Eastern European countries, and finally China lowering the rank of its diplomatic relations with Vilnius. China’s relations with the EU as a whole have also deteriorated in that time, which could have prompted its harsher reaction towards Lithuania.

A strategic boycott

China’s trade with Lithuania is of marginal importance even from Vilnius’s point of view; turnover with the PRC is only 1% of its total trade. But China is not only working to curb its trade with Lithuania. In fact, Beijing intends to achieve a broader and more complex effect: to devastate the cooperative ties in the Baltic economy, and threaten the cohesion of European integration.

Lithuania is a small, open economy which draws its strength from participating in international supply chains for semi-finished products created by global corporations. Thanks to EU membership, tax incentives and good infrastructure, it has managed to attract a great deal of direct investment. This is the target of the Chinese boycott. According to its assumptions, no product containing components from Lithuania should reach the Chinese market; and no semi-finished goods from the PRC, where international companies also have factories, will be shipped to Lithuania. Beijing calculates that big business, faced with the risk of disrupting supplies, will start to pressurise Vilnius to withdraw from its ‘confrontational’ decisions.

The boycott also serves as a way of striking at the EU, with whom China’s relations have deteriorated significantly recently. Brussels has begun to examine the expansion of Chinese technology companies (5G) more closely; it suspended the ratification of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) signed in December 2020, and in March 2021 it introduced sanctions in light of the mass-scale violations of the Uighurs’ rights. The dispute with Lithuania is an opportunity to test the coherence of the internal market – the cornerstone of the Community’s economic integration – and challenge the exclusive competence of the European Commission to guide EU trade policy. Beijing hopes that Brussels will be unable to prepare a quick and effective response, which will weaken its authority and provoke some member states to put more or less open pressure on Lithuania to soften its position. In this way it can also test how seriously Europeans treat the EU’s ‘strategic autonomy’, the vision whereby Europe can act in the defence of its own interests and values at the global level.

A problem for Germany

Germany is one of the countries particularly exposed to the effects of the Lithuanian-Chinese dispute. In the first place, Beijing’s moves mean problems for German companies present in Lithuania. Large concerns such as Continental, Siemens, Bosch, BASF and Hella, as well as many medium-sized companies (the so-called Mittelstand), have invested in this country. Their factories, which are part of cross-border supply networks, produce quite technologically advanced components. For example, Continental (a subcontractor for automotive companies) opened a factory in Kaunas in 2019 which makes sensors for self-driving cars and interactive films integrated with car windows.

Some companies have already received warnings from the Chinese authorities about ‘customs problems’ related to trade with Lithuania. In this situation, they have begun to turn to business organisations and decision-makers for help. In mid-December, the German-Baltic Chamber of Commerce and Industry (AHK Balticum) complained to the government in Vilnius about the damage being suffered by German companies, and at the same time called for a ‘constructive solution’ to the dispute with China to be sought – otherwise, some companies could even be forced to relocate their production. Business representatives have also taken action in Germany. There was a plan for company managers and the AHK to meet economy minister Robert Habeck regarding the embargo, although there is no official trace of such talks having happened.

However, Germany’s problem goes far beyond the possible losses to the companies involved: it concerns political issues, and the question of how to react to the Chinese boycott. Even if the ‘autonomous’ action taken by the Vilnius government has irritated Berlin, criticising it openly is out of the question. Germany must support Lithuania – its ally in NATO, its EU partner and a country that has decided to take principled action against an authoritarian power. Moreover, Germany cannot ignore an attempt at blackmail instigated from outside, which could undermine the cohesion of the common market and fuel divisions within the Union. In fact, Germany should react by calling for swift retaliation against Beijing by the Community.

However, it was difficult to find clear signs of such determination in the initial reactions. Although there were declarations about ‘speaking with one voice’ (from the deputy economy minister Franziska Brantner) and criticism of China’s actions from Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, no strong lead has been taken by the Chancellor’s office, for example. The German government’s prudence could naturally be understood as recognising that the competences of the European Commission take priority in this matter. However, the more likely reason for Berlin’s caution is the awareness of Germany’s huge economic dependence on the PRC and the fear of what the dispute might cost. It may also be relevant that some political elites still believe in the idea of ‘change through trade’ (Wandel durch Handel).

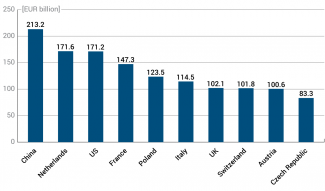

Chart. Germany’s trade turnover: its most important partners in 2020

Source: Destatis.

Dependence on China

The Chinese economy – the second largest GDP in the world – dominates German trade statistics. The country’s trade with the PRC exceeded €213 billion in 2020, and is over €40 billion greater than with the US. German dependence on China is also visible in the scale of foreign direct investments (FDI): by 2018 companies from Germany had invested almost €90 billion there.

However, these figures – which are already colossal – cannot express the qualitative dimension of the trade being discussed. German business, encouraged by successive governments under Angela Merkel, has built up its global production chains based on components supplied from and to China. For some companies, the PRC has become the most important outlet for finished goods. For example: car companies make a significant part of their total profits there (up to 30–50%), and based on the growing scale of their connections with local firms, it can be concluded that they are counting on even more. In 2020, the Volkswagen Group sold 3.75 million cars in China (almost three times more than in Europe), of which only 171,000 were imported. In turn, at the end of 2021 BMW announced it was transferring part of its production from the US to China (to a joint venture with the company Briliance). Daimler (and from February 2022, Mercedes-Benz), whose largest external shareholder is the Chinese state-owned enterprise and holding company BAIC, is also stepping up its Chinese cooperation. However, building a position on the Chinese market is not easy, even for such large companies as automotive firms. The local authorities play hardball when negotiating any concessions, such as cooperation with local producers or sharing technology.

Thus, Germany’s economic sensitivity to any possible trade war is high: losses in China would mean serious problems for the state in key industrial sectors, and in the longer term, the risk of a collapse in share prices on the Frankfurt stock exchange, a drop in tax revenues, and increased unemployment. Business often uses the projection of threats to warn German government off adopting a more principled policy towards Beijing. Recently Roland Busch, the head of Siemens and chairman of the Asia-Pacific Economic Commission (Asien-Pazifik-Ausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft), said that Minister Baerbock’s harsh criticism of slave labour in China could hinder the import of solar panels, and thus harm the energy transition – one of the government coalition’s most important undertakings.

However, not all companies support a soft attitude towards the PRC. The Federation of German Industries (Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie, BDI) has repeatedly pointed out that German companies are facing increasingly difficult operating conditions there. Political pressure from the Chinese authorities, arbitrary regulations, the compulsion to make technology available – all this is contrary to the principle of equal treatment for economic entities. German business’s tolerance of such practices is declining as concerns about Chinese competition grow. These concerns are justified: in 2020, the PRC overtook Germany as world leaders in machine exports (€165 billion vs €162 billion). That is why there will be more and more demands for preventive action, such as the Ministry of Economy’s supervision of the Chinese company Midea’s acquisition of the robot manufacturer Kuka in 2018. Nevertheless, even if the mood among German manufacturers is gradually changing, it is hard to assume their immediate support for tough retaliation against China for its trade boycott.

The belief in ‘change through trade’

Another factor preventing Germany from reacting more strongly to China’s boycott of Vilnius is the conviction, still alive among many in the elites, that trade liberalisation, economic exchange and an open global economy are effective long-term policy tools for democratisation, the protection of human rights and the prevention of armed conflicts. In this worldview, the development of economic cooperation with authoritarian regimes is deeply justified: trade and investment should lead to interdependence, and gradually encourage such regimes to greater openness, and ultimately to liberal transformation. In practice, this idea has turned out to be deceptive, but it has undoubtedly allowed business to expand profitably into global markets.

The idea of change through trade also fit well into rising economic ties and Berlin’s patience with expanding authoritarianism in China. So, Merkel’s governments were very involved in boosting commercial cooperation with the country, but remained rather hesitant to highlight Beijing’s human rights violations. Opponents of this approach raised the problem of a gradual loss of credibility in Germany’s foreign policy, which found itself increasingly torn between its economic interests & normative assumptions and the promotion of democracy. This was especially emphasised by the representatives of the Greens and the FDP – parties which have been in the ruling coalition since last autumn. Their statements more and more clearly demonstrate the conviction that relations with Beijing are already part of a ‘competition of systems’ in which sharp conflicts – including trade restrictions – are virtually inevitable.

Under the umbrella of the EU

Germany is not yet ready to take the initiative in the dispute between Lithuania and the PRC: it is too afraid of the economic costs of an open conflict with Beijing, and the country’s elite is still leaning on the vision of Germany as a non-confrontational ‘trading state’. On the other hand, Berlin wants to avoid the impression of making concessions to an authoritarian power, especially since it already has to explain its submissive policy towards Russia in these terms. This is probably why Chancellor Olaf Scholz has finally decided to raise the issue of the boycott in a conversation with Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang.

However, it is hard to expect that Berlin currently has anything more in its portfolio than general declarations of support for Vilnius and making diplomatic efforts in its relations with Beijing. Germany hopes that since China’s relations with the US have worsened, it will be more dependent on cooperation with them, and will not risk escalating the situation. Berlin’s dialogue with the PRC may allow it to ‘buy time’ and neutralise the effects of the conflict, for example by introducing solutions which would mitigate the effects of boycotts on companies, and perhaps even establishing a compensation fund (provided that German businesses continue to operate in Lithuania).

From Berlin’s point of view, it is best to leave the key political actions and tough declarations in the Lithuanian-Chinese dispute to officials of the European Commission, which has the formal authority in matters of trade policy. On 27 January the commissioner responsible, Valdis Dombrovskis, submitted a request to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to initiate proceedings against the PRC for using discriminatory practices in the exchange of goods and services. The Commission also announced it was speeding up work on a sanctions mechanism aimed at countries which put economic pressure on EU members (an anti-coercion instrument). In this situation, Germany can count on China needing it as a partner to blunt the edge of the EU’s retaliation – and being even readier to initiate a bilateral dialogue.

Transferring this issue to the EU level has one more advantage: thanks to this, it will be possible for Berlin to indirectly criticise Vilnius for taking actions it has not agreed with its partners, and to use the situation to push for a reform of the integration process. As Germany sees it, the dispute with the PRC has revealed a significant structural problem for the EU: decisions taken independently by a member state in areas not covered by integration may have effects throughout the Community. Therefore, the role of the EU institutions should be strengthened, and in particular, the scope of majority voting in the European Council should be expanded – including in foreign policy.

France’s assumption of the EU presidency in the first half of 2022 is a stroke of luck for Berlin. President Emmanuel Macron may want to take advantage of Lithuania’s conflict with China to adopt a more confrontational course with Beijing, and to advertise the concept of Europe’s strategic sovereignty. Along the way, it may encourage Central European countries to abandon cooperation with China in the 16+1 format, which both Paris and Berlin have always viewed critically. France is not risking as much as Germany: its trade dependence on the PRC is far smaller, and it has invested less there. It is therefore possible that the cards in the game with Beijing have already been dealt: Paris and Brussels will play the role of the ‘bad cops’, while Berlin can appear as the mediator and broker of political compromises.