One year of war. Russia’s imperial maximalism versus Ukraine’s resistance

A war that almost nobody expected has been ongoing for a year now. Although reports suggesting that Russia may be preparing for war had emerged at least several months prior to 24 February 2022, there was no consensus among politicians and experts on how these reports should be interpreted. The most popular interpretation argued that we were witnessing Russia putting political and psychological pressure on the West, a bluff applied by Moscow to force the West to agree to a profound revision of the security order, to Russia’s advantage.

When in mid-December 2021 Moscow presented the West with its ultimatum, in an analysis prepared by Marek Menkiszak, the head of OSW’s Russian Department, we wrote that “the Kremlin has most likely decided to make an attempt to fundamentally change the status quo in the political and security sphere in Europe through unilateral actions that aggravate the international situation, including possibly military actions. These may particularly include armed aggression against Ukraine”. We believed that a war was imminent but viewed a full-scale invasion as “the least likely scenario, but one that cannot be ruled out”. The OSW team held numerous debates on this issue and formulated different, sometimes quite divergent, forecasts. Due the fundamental changes that happened in Ukraine post-2014 at the social and political level and as regards the armed forces, it seemed unlikely to us that the Kremlin was so detached from reality that it failed to understand these new circumstances.

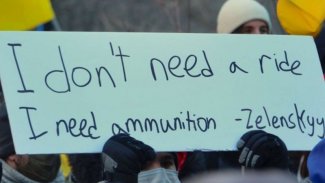

Initially, US intelligence presented increasingly alarming reports to the allies and to the public in a manner unprecedented in modern history. These did not, though, impress the government in Kyiv. Until the final weeks prior to the Russian invasion, President Volodymyr Zelensky manifested his scepticism about these reports. Two weeks into the invasion, the head of the President’s Office Andriy Yermak, who is considered the second most influential figure in Ukraine, gave a frank interview in which he said that, “until the very end we did not believe that this would happen. We had lots of information from our partners but we still did not believe it”. Despite this, Ukrainians began preparing for their country’s defence “just in case”.

The prospect of Vladimir Putin unleashing a great war was also beyond the strategic imagination of the vast majority of Western elites which continued to be distrustful of the increasingly disturbing reports presented by Washington. Several months following America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, which had been carried out in a disastrous manner, the reputation of US intelligence was tarnished. And on 24 February 2022 Russia attacked Ukraine across the length of their common border, from air, from sea and also from the territory of Belarus (which also came as a surprise to Kyiv).

A surprisingly difficult opponent

By starting a war, Putin intended to play a quick game of poker. However, it soon turned out that he had begun a long and debilitating conflict. The Russians have made a classic mistake in underestimating their opponent. From the first hours of the invasion, it was clear in their methods of planning and conducting the hostilities that they had underestimated and deprecated the Ukrainians just as they had done many times in the past. The Kremlin denies Ukrainians the right to exist as a separate nation and Russian state media propaganda demonises and dehumanises them, and calls for their ‘de-Nazification’.

Soon after attacking Ukraine, a state which, according to Putin’s words, was “entirely created by Russia”, the Russian war machine met with strong resistance from the Ukrainian armed forces and Ukrainian society as a whole. The nationwide mass-scale activation of Ukrainians to defend their independence, freedom and lives, combined with the absence of major instances of collaboration with the aggressor, prove that Ukrainian statehood is a permanent element of Europe’s political map and that Ukrainian identity is stronger than at any point in the nation’s history.

After the initial successes in its first weeks, the Russian offensive began to collapse and Russia decided to withdraw from some of the captured territories, as it was unable to break through the Ukrainian defences. This enabled the Ukrainians to gradually recapture the northern part of Kyiv Oblast, as well as Chernihiv and Sumy oblasts and portions of Kharkiv and Kherson oblasts. In late summer and early autumn, using the support provided by the Western states, the Ukrainians launched a daring counteroffensive and recaptured the remaining portion of Kharkiv Oblast, and then forced the Russians to withdraw from the right-bank portion of Kherson Oblast. To avoid being defeated at the front, in September the Kremlin had to announce a mobilisation, which revealed Russia’s weakness when compared to Ukraine’s determined defence. Military aid from the West was of major importance because without it the Ukrainian armed forces would not have been able to confront Russia.

However, Ukraine is paying a huge price for its fight for sovereignty. It involves tens of thousands of civilian casualties and the still undisclosed but definitely very high number of military casualties, the destruction of cities situated in the areas of fighting, major disruptions to the economy, serious damage to energy and transport infrastructure, a traumatised society, millions of refugees. In his Christmas address, President Zelensky, the unquestioned hero of this war and an icon of global freedom, expressed what the vast majority of Ukrainians sign up to: “Freedom comes at a high price. But slavery has an even higher price”. Ukrainians are aware that the ongoing war is not only a fight for their state’s sovereignty but also an existential conflict.

Much to his surprise, Putin’s game, which had been focused on Ukraine, suddenly turned into his own struggle to remain in power. Although at present there are no indications that in the short-term perspective a political crisis could emerge in Russia, this scenario cannot be ruled out. Either Russia’s defeat or the absence of its victory in the war will have significant consequences for its stability. Historical analogies naturally come to mind. One may speculate on the degree to which the Russian aggression against Ukraine resulted from the domestic political needs of the Putin regime (for example to consolidate society and divert its attention from other problems). There is no doubt that the war has changed Russia profoundly. This is manifested in the surge in repression, mass-scale indoctrination of citizens in all spheres of life, and the disappearance of the remnants of pluralism. The Russian state under Putin has returned to Soviet totalitarian practices.

Russia’s war with Ukraine is not a local conflict. Although twelve months have passed, for some this view is still far from obvious. Russia does not intend to seize one or another Ukrainian region. This is not a war for territory. The Kremlin regime has unleashed a war for control of Ukraine as a whole, and this is also a war with the West. What is at stake is a profound revision of the international order in Europe. Its consequences will have a global impact. Incidentally, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov admitted this several weeks after the launch of the invasion: “It is not about Ukraine at all. It is about the world order. The present crisis is an epoch-making moment in contemporary history that will have significant consequences. It is a battle, in the broadest sense of this word, for how this global order will be shaped”.

Russia’s zero-sum game

The most important and the most difficult question regarding this year-long war concerns its most likely outcome. So far, there are no indications that the hostilities could end soon. Russia has failed to attain its goals, and its official annexation of a portion of Ukrainian territory in September 2022 can only be viewed as an attempt to conceal its weaknesses. Despite this, the Kremlin is not going to stop. Its strategic goals continue to be the same as they were on 24 February 2022. The only new element is the realisation that attaining them will be more difficult and will last longer than the Russian leadership had initially expected. Moscow has changed its tactics and is now expecting a long war. In addition, it wants to create the impression that its consistency and determination will ultimately help it to win. However, a prolonged conflict is also generating numerous risks for the Kremlin regime.

In an attempt to understand Russia’s attitude in the current war, it is worth focusing on issues that go beyond what is at stake in this conflict and beyond the conviction that the war marks a turning point in Russia’s history. Marian Zdziechowski (1861–1938), a prominent historian of ideas, expert on Russian philosophy and rector of the Stefan Batory University in Vilnius, argued that maximalism is the most characteristic feature of the Russian modus operandi. More than a century ago he wrote: “Maximalism reduces everything to a dilemma: all or nothing… it is natural that maximalism transforms itself into a negation of reality, into a blind and ruthlessly cruel destructive force operating in all aspects of the moral, social and state system”. It seems that this assessment can prove helpful in understanding the present attitude of the Kremlin elite which is convinced that it is playing a zero-sum game.

The Kremlin will not stop by itself. However, Russian imperial maximalism has come into contact with exceptionally strong Ukrainian resistance. Neither the leadership in Kyiv nor the Ukrainian public is willing to make any concessions or agree to ‘difficult compromises’. Nobody in Ukraine is prepared to give a single inch of Ukrainian territory to Russia. There is a broad nationwide consensus which views Russia as a deadly threat. Ukrainian-Russian relations have ultimately parted their ways, which is a symbolic reversal of the 1654 Pereyaslav Agreement. This is of historic significance for the balance of power in Eastern Europe (and in Europe as a whole).

At present, both parties are hoping to resolve the conflict on the battlefield, which rules out any negotiations. Zelensky, who is excellent at interpreting public sentiment, is aware that his potential consent to any unfavourable agreement with the Kremlin would equate to political suicide. Therefore, in an attempt to dispel doubts, on 30 September he signed a decree stating that “it is not possible to conduct negotiations with President Vladimir Putin”. At the same time, from the Kremlin’s point of view, the conditions formulated by Kyiv in the context of potential negotiations with Russia are unacceptable for obvious reasons (they envisage the aggressor’s withdrawal from all of Ukrainian territory, the pledge that all individuals guilty of crimes will be punished, and the payment of reparations).

The war will last

The Russian-Ukrainian front, which currently stretches across around 1,000 kilometres, has been stalled since last October. Kyiv is expecting a major offensive from Russia. In the most optimistic scenario (from the Russian point of view) the would lead Russia to victory. In a pessimistic but acceptable variant, it would create conditions for peace talks and result in a relatively long period of ‘rest’ for Russian troops. Other consequences of the escalation of the conflict would involve decreased discipline among Ukrainian soldiers, the emergence of new internal divisions in Ukraine and, ultimately, a further destabilisation of Ukraine’s socio-political situation. This indicates that this tactic is Russia’s attempt to set a trap for Ukraine. However, there are no indications that the united and highly motivated Ukrainian defenders would fall into this trap. Their determination and resistance are continuing and are unlikely to dwindle.

The West is where the Kremlin has vested its main hopes. Russia’s continuously aggressive rhetoric, its regular nuclear threats and its intention to exacerbate the energy and economic crisis in the EU are intended to discourage the Western elite and societies. Russia is hoping that they will blink first. And although the instruments of propaganda and information campaigns that Russia is using against the West are not as effective as they had been prior to 24 February 2022, Russian activity in social networks has increased in order to provoke further divisions within the Western world.

However, at this point, there are no indications that the power of the West’s response to Russian aggression will radically diminish. This is another development that came as a surprise to the Kremlin. Many Western states, in particular Poland and other countries on NATO’s eastern flank, understand that the stakes are very high. Long-term military support from the West as a whole is an essential precondition for a Ukrainian victory.

A year into the Russian invasion, it is evident that the war will last, although probably with varying intensity. At present, there are no prospects for peace talks and potential concessions from either side. It is of fundamental importance to provide the Ukrainians with weapons and equipment to help them defend themselves. This will not be possible without further increased Western supplies. For the time being, the conflict over the future of Ukraine and the new international order remains unresolved. However, the good news is that the dynamics of military activity over the last year prove that Putin has unleashed a war he is unable to win.