Far behind Riga: Latvia’s problems with uneven development

Latvia’s economic situation is gradually deteriorating due to its uneven development. One of the main reasons for this is that the metropolis of Riga accounts for as much as two-thirds of the country’s economic growth. Economic and social indicators for Latvia’s regions are sometimes several times lower than those for its capital. The non-metropolitan areas are struggling with numerous problems: high unemployment, an aging population, deteriorating living standards, insufficient medical care, or a shrinking network of educational institutions. Another important fact is that local governments often function like ‘appanage principalities’. If the current trends continue, the state will continue to fall behind its neighbours Estonia and Lithuania.

Centralisation

Since regaining independence, Latvia has had impressive economic growth. Between 2000 and 2007, together with the other Baltic states, it led the way in this respect in Europe. These countries, which at that time were popularly referred to as the ‘Baltic tigers’, were developing at a rate of 10% annually. Although the Latvian economy was hit hard by the financial crisis of 2007–9, its GDP had been steadily growing (by an average of 3–4% per year) until the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, and unemployment was at a relatively low level of 6–8%. Such positive results were largely due to the rapid development of Riga; the data in the rest of the country deviated more and more from those concerning the Riga metropolitan area.

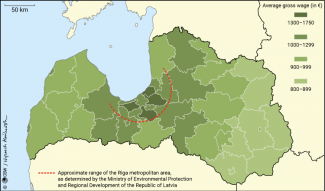

This rapid economic growth has not bridged the gap between the centre and the periphery. To a large extent, the problem results from the structure of the state. Latvia is one of the EU’s most territorially centralised countries; socio-economic life is concentrated around the Riga metropolitan area, which has about 850,000 residents (the country’s total population is 1.83 million people).

Map 1. The Riga metropolitan area contrasted with the average income in Latvia in 2021

Source: Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development of the Republic of Latvia.

Riga and the area around it generate up to 69% of Latvia’s GDP[1]. In practice, this means that the state is clearly divided into a strong centre, concentrated within a small area, and the extensive peripheries. The living standards in and around Riga are similar to those seen in the capital regions of the country’s Baltic neighbours. However, the gap between it and the rest of the country is much more noticeable than in Lithuania and Estonia[2]. The other two Baltic states, apart from their strongly developed capitals, also have cities that function as local development centres (such as Kaunas and Tartu). The major regional differences in Latvia have a strong impact on the economic indicators: the worse connected, poorer and ageing outskirts are characterised by poorer economic results and socio-economic backwardness as compared to the equivalent areas in neighbouring countries.

The development gap between different parts of the country is illustrated by socio-economic data for the last few years concerning unemployment, migration (internal and external), average household income and the percentage of people living below the subsistence minimum. Particular attention should be paid to average household income (Table 1) and the scale of unemployment (Table 2).

Table 1. Average monthly household income in Latvia in 2021

Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia.

The farther away from the centre, the poorer Latvian households are. The worst situation is in Latgale; the average income of a statistical household in this region is almost half that of the prosperous suburbs of Riga.

Table 2. Unemployment rate in Latvia and its individual regions 2011–2021

Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia.

The unemployment figures are inversely proportional to average household incomes. For many years, these figures have been highest in the poorest, eastern part of the country and the lowest in the municipalities around the capital. Recently, the average unemployment rate in the Riga agglomeration has been only a half or a third that of the poorest region, Latgale. The differences between the capital (and its agglomeration) and the southern and western regions of Latvia are smaller.

The significant proportion of people living in poverty is a serious problem in regions located far from the capital. While only 4–5% of the population in the Riga metropolitan area had incomes below the minimal level in recent years, this share was up to 9–10% in the periphery, and as much as 14% in Latgale.

A relative improvement in the labour market was seen between 2017 and 2022. The unemployment rate fell significantly in the regions, partly as a result of internal migration and emigration (during this period 20,000 people left the country permanently)[3]. Two trends are crucial for the mobility of Latvian residents. The first is the move from the provinces to the larger towns and cities. On the national scale, this applies mainly to Riga, and on the local scale this translates into moving from suburban areas to Daugavpils, Ventspils and Liepaja.

Chart 1. Net migration of Latvian population in 1990–2021

Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia.

Another important phenomenon is the ongoing expansion of Riga, that is, its suburbanisation and semi-urbanisation of the municipalities around it. Over the past decade, the number of people, mainly representatives of the middle and upper classes, moving from the central districts of Riga to the suburbs has been increasing. This has led to the formation of a ‘rich ring’ around the capital over the past decade. At the same time, the centre of Riga keeps degrading as a consequence of the pandemic crisis. This is manifested in the growing number of housing and office spaces lying vacant, and the shift of public life to other districts.

As already mentioned, emigration has also had a strong impact on the asymmetry between the centre and the periphery. Over the past decade, it has affected all parts of the country fairly evenly, but its consequences are having a more severe impact on the regions far from the capital. Riga has offset the decline of working-age residents by taking in those who have migrated within the country.

Continuing depopulation

Migration is having a major impact on the ageing of the periphery. The average age of residents is lowest in Riga and its surroundings: in the capital it is 42 years, and in suburban Ādaži and Mārupe it is 38 and 34 years respectively. The municipalities with the oldest population are located in Latgale, where the average age for the entire region is 45 years. The figures are highest in the municipalities located next to the eastern border. A resident of the Krāslava Municipality is 47 years old on average.

Map 2. Average age of residents of individual regions of Latvia

Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia.

The poorest and oldest municipalities have the biggest problem with demography. The proportion of active (aged 16–64) and economically inactive (aged 0–15 and 65+) residents is most unfavourable in the east of the country. For example, Daugavpils and Rēzekne have more residents of pre-working and post-working age than those who are professionally active. In Latgale and in the west, in Kurzeme, the share of pensioners is as high as 25%. The situation is only slightly better in Vidzeme and Zemgale, where they constitute 20% of the population.

The age dependency[4], and the ensuing ‘shrinking’ of social infrastructure, the problems on the labour market and the lack of demographic renewal are strongly affecting local governments. Not only does the deteriorating demographic situation have a negative impact on the quality of life, but it also increases the operating costs of local government units. The falling number of children and the growing percentage of pensioners are already resulting in the closure of educational institutions. At the same time, the demand for support centres for the elderly, such as hospices and nursing homes, is increasing. In some Latvian municipalities, the transformation of the social infrastructure is already becoming visible. Closed schools are being transformed into support institutions for the elderly. The absence of medical assistance points and the deepening problem of transport exclusion will also pose increasing challenges. Residents of some municipalities which are remote from medical centres are finding it difficult to use their services. These trends are unlikely to change unless external support is provided, and central and local governments take joint action.

The local government ‘principalities’

Latvia’s central government is aware of the increasingly pronounced differences in development at both the national and regional levels, and the need to reverse the existing trends as soon as possible. It is assumed that the sustainable development strategy for 2021–7 developed by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development will help eliminate the problems. This is aimed at supporting local entrepreneurship, increasing productivity, attracting human resources to the periphery, and creating regional knowledge and innovation systems. These plans are to be financed from three instruments: EU funds, central & local budgets, and Norwegian & Swiss funds or grants. Some of the tasks specified in the document are already being implemented. In 2016, special economic zones (SEZ) were created in some regions, including Latgale, in order to reverse these trends. However, the investments made so far (many of them worth millions of euros) have had little impact. For example, the projects launched in the Latgale SEZ usually cover modern production plants requiring small but highly specialised staffs, and so they cannot solve the problems of the local labour market.

The lack of appropriate investments and resources stand in the way of implementing the plans presented by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development. Another serious obstacle is the state governance model and the local political culture. Local governments in Latvia often function like ‘appanage principalities’ where strong local elites are in power. Some units have even been conducting independent foreign or economic policies. For example, Riga maintained special relations with Moscow when it was governed by Nils Ušakovs in 2009–19. A similar phenomenon was seen in the port city of Ventspils, which needed to maintain good economic relations (mainly transit) with Russia and Belarus in order to develop. Until 2021 it was governed by Aivars Lembergs, who has business links with Russia. Similar processes are also taking place in the eastern regions, where cooperation with Latvia’s eastern and southern neighbours plays an important role. For example, in recent years Latgalian local governments have maintained close foreign contacts enhancing economic cooperation with Belarus, amongst other countries. As a consequence, the development priorities set by the central government have not always gone hand in hand with the visions of local authorities. In many cases, the relatively strong position of local government officials translates into distrust between the centre and the regions, especially when a local government party is engaged in a political dispute with the central government.

Another problem in contacts between the centre and the periphery is the political animosity swamping Latvia. The centre-right parties, which have governed the country for years, believe that some of their rival groupings are harmful to the state, and have surrounded them with a kind of political cordon sanitaire. As a consequence, for example, local governments in the east governed by the ‘Harmony’ Social Democratic Party are sometimes treated as a foreign body within the state. This political polarisation makes it more difficult to implement any development strategies in Latvia.

The Baltic asymmetries

The development gap between the centre and the periphery will continue to widen. This will increase the social and economic disparities between Latvia and the other Baltic states. It is already obvious that Latvia is falling behind its neighbours. This is visible in the economic data and social surveys of statistical offices, as well as in the information provided by the European institutions. Lithuania overtook Latvia in terms of GDP per capita a decade ago, and the gap between the two economies has been widening over the past four years.

Chart 2. GDP growth per capita in constant prices in individual Baltic states in 1995–2021

Source: World Bank.

Latvia is also lagging behind the other Baltic states in terms of the size and growth rate of wages. The average net wage in the second quarter of 2022 was lower than in Estonia and Lithuania by €400 and €100 respectively. The differences also concern the minimum wage. At present, Latvia (€620) is among the lowest-ranking EU countries in this respect (only two countries, Romania and Bulgaria, are behind it), while in 2018 it was almost equal to Lithuania. The value of the basic basket of goods and services in individual Baltic states before the inflation spike in 2022 was similar; Latvia was only distinguished by slightly higher food prices. This means that the cost of living there is higher than in the rest of the region.

Table 3. Wages in individual Baltic states

![]()

Source: statistical offices of the Baltic states.

Latvia has a much bigger migration problem than the rest of the Baltic states, even though the 2007–9 banking crisis (after the collapse of the US loan market) hit each of them quite severely in this respect. Negative migration trends have been weakened in Lithuania and Estonia, where a positive migration balance has been seen for several years. This is an effect of the economic growth observed in these countries, which has triggered inflows of economic immigrants from outside the EU (mainly from the countries of the former USSR). This trend is so strong that the Estonian labour market is even beginning to attract Latvians as well. Over the last decade, their number in Estonia has increased by two and a half times. In addition, Latvian frontier residents tend to use the services provided on the Estonian side of the border and work there more and more often.

Is Latvia in danger of collapse?

The recent attempts to solve structural problems, mainly through the establishment of the SEZs, may prove insufficient. In the coming years, the development gap between the centre and the periphery is likely to increase. It will be particularly visible between the rich suburbs of Riga and Latgale, which is Latvia’s poorest region. The region’s situation will also be affected by the consequences of the war in Ukraine (including the breaking of some economic ties with Russia and Belarus).

The problems of the poorest region will eventually affect other parts of the country. According to estimates, by 2030 almost half of Latvia’s population will be over 50 years old, and the number of economically active people will fall by a fifth. In the coming years, Riga’s development will slow down, which will have a negative impact on the rest of the rich agglomeration. The post-pandemic economic recovery in Riga also seems to be proceeding more slowly than in Vilnius and Tallinn.

Chart 3. Projected population of Latvia in 2030, 2040 and 2050

Source: UN estimates.

Immigration could change Latvia’s situation in the short run. However, it is unlikely to increase because the Latvian public does not want people from outside the European cultural circle to come to their country. From the Latvian perspective, the influx of Russian-speaking citizens from the former Soviet republics is also problematic. The exception are Ukrainians, whose greater presence now seems acceptable[5]. The demographic gap could also be filled as a result of the re-emigration of Latvians living in other EU countries. For any of these scenarios to come true, an appealing offer to encourage people to settle in Latvian regions would have to be created. Unless the infrastructure (hospitals, schools, transport) and economic conditions improve, however, the prospects for re-emigration or immigration from selected countries will remain unrealistic.

The state could also benefit from improving the domestic political situation. This could be achieved by reducing the ethno-political divides between the Latvian-speaking majority and the Russian-speaking minority. The centre-right groupings representing the Latvian-speaking part of the population continue to isolate the parties elected by the Russian-speaking population. This causes distrust, for example, between local governments in Latgale, governed by politicians from the lists of the ‘Harmony’ Social Democratic Party, and the centre-right central government. Lowering the temperature of political disputes and eliminating polarisation would certainly offer more chances for interregional cooperation and, as a result, for gradually bridging the development gap. Unfortunately, the ongoing war in Ukraine is only adding to the divides among the Latvian public[6].

In the long run, Latvia will most likely continue its fall into impoverishment, and the development gap between it and the other two Baltic states will further grow. Economically, the country will gradually move closer to the least developed European nations (the poorer Balkan countries) and lag behind the wealthier northern part of the Old Continent.

[1] Regions and Cities at a Glance 2018 – LATVIA, OECD, 5 March 2019, p. 3, oecd.org.

[2] The other Baltic states are developing more evenly than Latvia. Medium-sized cities in Lithuania and Estonia serve as competitive development centres to their capitals; at the same time, they are much better connected to the ‘centre’ than Latvian cities. Lithuania and Estonia also have prestigious universities located outside the capitals. This is particularly evident in Estonia: Tartu is a more influential academic centre than Tallinn.

[3] Over the last three decades about 468,000 people have left the country. In general, the number of Latvia’s residents has decreased throughout this period (as a result of emigration and negative natural growth) by about 700,000.

[4] Age dependency is the ratio of the number of people of pre- and post-working age to the size of the working-age population.

[5] At the turn of December 2022 and January 2023, there were about 33,000 Ukrainian refugees in Latvia. 11,000 of them have the right to work.

[6] B. Chmielewski, J. Hyndle-Hussein, ‘Łotewskie batalie o pomniki’, OSW Commentary, no. 458, 24 June 2022, osw.waw.pl.