‘The silence of the lambs’. Russian big business in wartime

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the sanctions that followed it have brought multi-billion losses to Russian big business. The magnitude of blows dealt to its main representatives has resulted in a shift in the business model they have applied thus far. Despite these losses, most Russian billionaires, just like Russian society, have tacitly come to terms with Moscow’s aggressive policy. Even those who reside abroad have not ventured to criticise the Kremlin, and instead have focused on adjusting their businesses to the new economic reality. Silence has been their main defensive strategy, enabling them to avoid being targeted by the Russian authorities.

In recent months, in the situation of Russia’s shrinking budgetary revenues, the future of the assets owned by billionaires who do not belong to the Kremlin’s closest circle has been threatened. It is very likely that members of the pro-Putin elite will expand their wealth at the cost of these billionaires. Moreover, it turned out that the assets which they had transferred to the West over the years are not safe either, for example due to Western sanctions. Despite their passive attitude towards the Russian government, these billionaires are actively involved in taking measures outside Russia which are intended to help them to retain their assets and maintain their current living standards.

As regards Vladimir Putin’s closest aides, the Kremlin has been seeking to make up for their losses to some degree by allowing them to earn money by providing war-related services to the state. They are also being awarded public tenders, and they can seize attractive assets from Russian private businesses and foreign companies which have decided to withdraw from the Russian market. Interestingly, even those businessmen who are closely linked to the Russian ruling elite have been reluctant to publicly declare their support for the Kremlin’s policy, and usually prefer not to speak about the war. Putin is using the invasion of Ukraine to increase the role of the state in the Russian economy and to consolidate the Russian form of state capitalism which has taken shape during his rule. As a consequence, Russia is witnessing a new wave of ownership transfers, efforts to curb competition, and the emergence of further mechanisms of corruption.

Losses suffered by big business

According to estimates prepared by the Bloomberg agency, over the first year of the full-scale war the value of assets owned by the 23 richest Russian businessmen has decreased by around $65 billion, that is, by around 20%.[1] The individuals most affected by this decrease include Roman Abramovich: the value of his assets has declined by more than 50% (see Table 1 in the Appendix). Russian billionaires have been affected not only by the devaluation of their companies’ stocks but also by the changes in the business environment. Most importantly, many Russian exporters and importers have lost their access to lucrative Western markets, including capital markets. For them, the process of adapting to the new economic reality entailed the need to increase cooperation with Asian states which offer much lower profit margins (this applies to raw materials in particular). It has also rendered the Russian economy increasingly technologically backward (because of the lack of access to Western technology and investment goods) and raised the costs of its logistical and financial operations. In addition, cooperation with Russia is increasingly being seen as risky; that is forcing Russian exporters to sell their raw materials at dumping prices, while importers pay inflated prices for the goods they buy.

Personal sanctions have been another blow to many Russian businessmen. As a result of these restrictions, assets located in Western states (financial assets, immovable and movable property) worth a total of around $60 billion[2] have been frozen. Moreover, these assets may be confiscated and used later for Ukraine’s reconstruction. As a result of the sanctions imposed, Russian businessmen and their family members have had to modify their lifestyles; for example, they are no longer able to travel to Western countries and have lost their position in international political and business circles, which now view contacts with them as toxic.

Combined with the mounting costs of the war, Russia’s economic crisis has forced the Kremlin to increase the fiscal burden shouldered by business. For example, in 2022, the government decided to seize the profits earned by Gazprom. However, companies operating in the metallurgical, coal mining and mineral fertiliser sectors have also been obliged to share their profits with the state budget. In 2023, these fiscal changes affected a much bigger group of companies. Not only did the government once again increase the fiscal burden shouldered by the oil and gas sector, but it also plans to strip big businesses operating in various sectors of the economy of a sizeable portion of the profits they earned over the last two years. Moreover, further tax increases may be introduced by the end of this year.

The billionaires’ reaction and their defensive strategies

Over the last twenty years, Russian big business has become completely subordinated to the Kremlin. Its activities both at home and abroad have come under close scrutiny by the authorities. As a consequence, the so-called oligarchs have disappeared from Russia’s political and economic system. Although Putin's elite allowed the billionaires to multiply their wealth, at the same time it built up instruments of pressure to target them with (such as the coercion apparatus and the judiciary, which is fully subordinate to the authorities) in order to strip them of their assets, damage their health or even kill them. Russian business has accepted these rules of the game: for example it transfers a portion of its profits to the Kremlin, sponsors its important initiatives and takes part in activities lobbying in favour of Russia’s interests abroad. Assets held by billionaires outside the Kremlin’s inner circle have come under threat in recent months as funds for distribution among the elite have begun to shrink. It is highly likely that the members of the pro-Putin elite will seek to expand their wealth at these individuals’ cost. As a result, the billionaires are increasingly concerned that some of their assets may be nationalised or seized by those who are more loyal to the Kremlin.[3]

As a consequence most billionaires, whether they reside in Russia or abroad, have decided to remain silent, viewing this as the best method of protecting their businesses. Despite the losses it has suffered, so far Russian big private business has not dared to criticise the Kremlin. In the first weeks of the invasion, very few businessmen decided to publicly call for peace (examples included the leadership of Lukoil and Novatek, and the business tycoons Oleg Deripaska and Mikhail Fridman). So far, the harshest words of criticism of the war and of its consequences (“states should be spending money on providing health care to their citizens, not on waging a war”) have come from Oleg Tinkov, a businessman residing outside Russia, who has never been a member of the Kremlin’s inner circle. As a consequence, he was stripped of his assets in Russia. According to Tinkov, most businessmen he knows have similar views but are afraid to express them in public.[4]

Russian billionaires turned out to be much more active in making efforts to protect their assets located abroad. To avoid having their assets frozen, individuals at risk of being covered by personal sanctions have mainly sold their property or registered it in someone else’s name (usually that of a family members). Aleksei Mordashov (the owner of Severstal and other companies) has registered his assets in his wife’s name, while Roman Abramovich (co-owner of Evraz and other companies) has handed over control of a major portion of his assets to his children. Mikhail Fridman and Pyotr Aven have left the board of directors of the LetterOne investment holding, while their business partners, Aleksey Kuzmichev and German Khan, have sold their stakes in LetterOne and Alfa-Bank; by doing this, they reduced the stake held by Russian stakeholders who have been covered by sanctions to less than 50%. Russian businessmen managed to relocate a major portion of their assets, including yachts and jets, from Western jurisdictions to other countries before the Western judicial bodies subjected them to restrictions. In most cases, they transferred their assets to states which have not imposed sanctions on Russia, such as the Persian Gulf states, Israel and Turkey.[5]

More than a hundred Russian billionaires covered by personal sanctions (including Abramovich and Fridman) have decided to file lawsuits in Western courts in which they are challenging the legitimacy of the restrictions imposed on them. Very few businessmen have offered any financial support to the victims of the war. Those who did have used this gesture as an argument in their attempts to have their names removed from sanction lists. For example, at the end of 2022 a charity controlled by Fridman, Aven and other businessmen announced its intention to offer support worth $10 million to Jews affected by the “crisis in Ukraine”. Abramovich, for his part, has declared that he will use the money obtained from selling Chelsea Football Club to fund humanitarian aid for war victims on both sides of the conflict.[6] He attempted to improve his image in the West by assuming the role of the Kremlin’s would-be intermediary during the peace talks with Ukraine which were held in the first months of the full-scale war, and also in the exchange of prisoners of war.

Some businessmen have attempted to regain control of their assets illegally. With the help of numerous frontmen and shell companies, Deripaska continued his business activity in the US (the mechanism was exposed in autumn 2022). Dmitri Mazepin and Alisher Usmanov, who have been covered by personal sanctions, recaptured the yachts they owned which had been ‘frozen’ by the authorities of Italy and Croatia respectively.

Despite the sanctions, most Russian billionaires have remained outside Russia. It should be noted that a great number of them have moved from Western states, mainly to Israel (Abramovich) and the Persian Gulf states (Andrei Melnichenko). Usmanov, who has collaborated closely with the Kremlin, has decided to move to his native country, that is Uzbekistan, and to reduce his business activity in Russia. Some businessmen have renounced Russian citizenship: these include Yuri Milner (a businessman active in the technology sector), who has resided outside Russia since 2014. Alongside Pavel Durov (a billionaire from the technology sector who owns the Telegram messaging platform), following the invasion of Ukraine Milner requested the Forbes magazine to cease referring to him as a Russian businessman. Any links to Russia are now viewed as a burden when doing business in the West. There are reports suggesting that only one billionaire, German Khan, has decided to return to Russia.

The silence of the billionaires has proved insufficient for the Kremlin. The authorities have stepped up their expectations that both citizens and business will give them active support, including their physical return to Russia. The government has also intensified its moves to force Russian business owners to remove their companies from foreign registers of businesses and re-register them in Russia. For example, in recent months companies owned by Vladimir Potanin, through which he controls the Norilsk Nickel company and other businesses, have been entered in the Russian business register. It is expected that the VK technology company, controlled by Putin’s friend Yuri Kovalchuk, will soon obtain the status of a Russian company. Billionaires who do not intend to return to Russia are increasingly frequently selling off their Russian assets. Arkady Volozh, founder and co-owner of the Yandex technology company, is attempting to separate off his stake and to transfer control of it away from himself, most likely to the company’s leadership. LetterOne, which is co-owned by Fridman and Aven, has been making attempts to sell the Russian stake in the VimpelCom mobile telephony operator to the company’s executive body. In addition, the same two billionaires hold 45.3% of the shares in Alfa-Bank, which has been subjected to sanctions imposed by the EU, the US and other countries. They are planning to sell their stake in the bank to Andrei Kosogovov, their business partner who resides in Russia; he himself already holds 41% of the bank’s assets because he bought German Khan’s and Aleksei Kuzmichev’s stakes in March 2022. However, it remains to be seen how these transactions will be finalised, who their final beneficiary will be, and whether the current stakeholders will actually receive any money in exchange for their assets.

Those billionaires who have decided to remain in Russia are focused on continuing their business activity and minimising their losses, and are using the present situation to continue to expand their wealth. Those who are loyal to the Kremlin can count on public tender contracts, financial support from the state and preferential terms of cooperation. Moreover, they benefit from some foreign companies leaving Russia. They take these businesses over, paying sums which are lower than their market valuation. Vladimir Potanin has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of this situation; for example, he bought Oleg Tinkov’s 35% stake in Tinkoff Bank at a relatively low price (see Table 2 in the Appendix).[7]

The main beneficiaries of the war

For individuals linked to the Russian defence sector, the war has become an opportunity to expand their wealth. At the same time, it has enabled them to cover up the traces of the vast corruption which has spread across this sector in recent years.[8] In 2022, Russia’s budgetary spending on national defence increased by at least 35% (i.e. by 1.2 trillion roubles, which is the equivalent of $18 billion) to 4.7 trillion roubles (around $70 billion). It should be noted, however, that this sum does not represent the total cost of the war: many of its costs are hidden in other budget categories including those relating to social policy, digitisation and economic development. Most of these funds have been spent on defence procurement, which is awarded at the discretion of the authorities, without the required tender procedures being held. Most of these contracts were carried out by the state-owned Rostekh company, which controls the vast majority of companies operating in the defence sector and is supervised by Sergei Chemezov (in the 1980s he served as a KGB officer in Dresden alongside Putin). Moreover, Rostekh has been the main recipient of state funds intended to subsidise imports. Chemezov’s increasing influence is corroborated by the fact that in July 2022 Denis Manturov, who is considered as his protégé, was promoted to deputy prime minister. Until that time, Manturov had been Russia’s minister of industry and trade. Manturov has consolidated control of defence procurement and the import substitution policy in his hands.

In recent months, Yuri Borisov gained direct access to budgetary funds, including those earmarked for defence procurement. In July 2022, Borisov was appointed as the CEO of the state-controlled Roskosmos company (in previous years he had served as deputy prime minister with responsibility for the defence sector). Roskosmos closely cooperates with the Russian Aerospace Forces. Defence procurement have also been awarded to companies linked to Borisov’s family (such as the Modul technology company and the Kingisepp Machine-Building Plant which manufactures and repairs diesel engines).

The Federal Agency for State Reserves (Gosrezerv) is another important source of opportunities for the ruling elite to expand its wealth in wartime. The agency’s task is to stockpile goods and materials for use during a war or in emergency situations (such as natural disasters). The main beneficiaries of tenders awarded by this agency include companies linked to the families of Sergei Chemezov, Nikolai Patrushev (the Secretary of Russia’s Security Council), Arkady Rotenberg (a billionaire and Putin’s judo sparring partner since their youth) and other individuals.[9]

Expansion at the cost of Western and Russian businesses

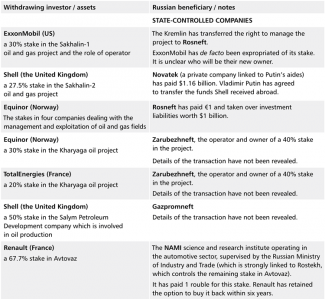

Members of the pro-Putin elite have also consolidated their position on the market by taking over the assets of Western companies which have decided to leave Russia, in particular energy sector companies. In most cases, the details of the transactions resulting in ownership structure change have not been revealed. The information available indicates that the new owners buy these assets at prices lower than their market value, and sometimes obtained by expropriating existing shareholders (such as the Sakhalin-1 energy project).

Another method of rewarding loyal individuals from the president’s closest circle involves enabling them to prey on state-controlled companies. For example Aurora, a company linked to Patrushev’s younger son Andrei, was allowed to lease certain elements of Gazprom’s Arctic fleet (including three out of Gazprom’s four platforms and several vessels) and to use the gas giant’s logo (Gazprom Shelfproject). This enabled it to become the main provider of drilling services in the Arctic shelf, including those commissioned by Gazprom and Novatek. Patrushev’s elder son Dmitri is using his position as Russia’s minister of agriculture and president of the management board of Rosselkhozbank (a state-controlled agricultural bank) to consolidate the agricultural sector and reap profits from it. Measures to facilitate this include market regulation (such as the distribution of export quotas), and supervision over the distribution of state subsidies offered to companies, and over who gets access to Rosselkhozbank’s preferential loans. Moreover, one of the most profitable segments of the agricultural market, the export of grain, has been strongly consolidated. In 2022, Russia’s ten biggest grain exporters accounted for the export of more than 70% of grain dispatched from the country (compared to 64% in 2021).[10] It is also worth noting that at least two of Russia’s biggest grain traders are linked to Dmitri Patrushev.

As regards the IT sector and the media, groups linked to Yuri Kovalchuk have recently expanded their influence. In August 2022, the Sogaz company controlled by Kovalchuk took over the Dzen and Novosti news services from Yandex. The Rostelecom state-controlled telecommunication company intends to dominate the mobile telephony market; for example it has made attempts to take over the MegaFon mobile operator, which Alisher Usmanov controls. In addition, the Russian media suggests that Rostelecom is seeking to take over VimpelCom.

Despite the war and the shrinking assets, the Rotenberg brothers are expanding their current business model based on preying on state-controlled companies and public tenders. Construction companies linked to Arkady Rotenberg and the VEB bank have been among the main beneficiaries of projects to develop rail and road infrastructure. In summer 2022, Boris Rotenberg entered the nuclear sector’s service market by taking over a 36% stake in the TechAtomStroi company, which is one of the subcontractors hired by the state-controlled Rosatom company.

Conclusions

As a result of the invasion of Ukraine and the sanctions that followed it, the entire Russian business sector, both state-controlled and private, has suffered financial losses. However, to date only very few billionaires have cautiously ventured calls for peace. The obedience displayed by the representatives of private businesses which are not closely linked to the Kremlin and of the billionaires who reside outside Russia results from them being intimidated.[11] They fear that they may lose their assets, or even be killed, should they openly challenge Putin. This actually indicates that business continues to be heavily influenced by the Kremlin.

The government in Moscow are using the war and the mounting crisis at home to continue to modify the ownership structure of the most important assets and to further consolidate state capitalism. Although its room for manoeuvre is shrinking, the state is mainly still supporting those companies which are closely linked to the Kremlin; for example, it offers them preferential loans and co-funds their projects. Moreover, as a result of legislative amendments (such as the decisions to abandon the open competition procedure when selecting contractors to carry out public tenders, and to classify information on beneficiaries of state contracts and the financial standing of state-owned companies), Russia has seen a rise in corruption.[12]

The Kremlin seeks to maintain the loyalty of individuals within its closest circle by compensating them for some of their losses and by awarding them lucrative public procurement. It also enables them to take over assets which used to belong to Western companies that have left Russia, or to Russian businesses owned by individuals who are not linked to the Kremlin. By allowing them to make money from the war, Putin is de facto increasing their joint responsibility for this war and for the crimes perpetrated during it. In this way, he is making their future increasingly dependent on the continuity of the present regime. Due to the hermetic nature of the Russian system of government, it is difficult to assess the true nature of the sentiments currently prevailing within the ruling elite. So far, no major conflicts over assets have come to light, although certain tensions within this elite are evident. However, these mainly concern the rivalry between individuals who are directly involved in the hostilities.

So far, Putin has successfully played the part of an arbiter: he resolves disputes and provides sufficient funds to be distributed later among his aides. However, the prolonged war and its mounting cost raise doubts as to how long the Kremlin will continue to have funds to meet the elite’s demands. The authorities have recently decided to target individuals from the Kremlin’s closest circle by increasing the fiscal burden they are expected to shoulder. Should the forecasts suggesting that in 2023 Russia’s financial standing may be worse than in 2022 prove correct, then Putin’s closest aides will need to rein in their appetites.

Russia’s former business model has been permanently damaged. Without access to Western markets, technology or investment goods, Russian big business will become increasingly dependent on the Asian market, in particular that of China. In these relations, Moscow’s negotiating position will be considerably weaker. As a consequence, the terms of such cooperation will be set by Beijing, and will most likely be much less favourable than those which applied during Russia’s cooperation with the West.

APPENDIX

Table 1. The value of assets owned by selected Russian billionaires (in billions of dollars)

Source: Bloomberg Billionaires Index, bloomberg.com.

Table 2. Selected transactions regarding the takeover of foreign assets in Russia since February 2022

Sources: the Russian media, press releases published by Western companies.

[1] J. Witzig, ‘Russia’s Richest Lose $67 Billion of Wealth After a Year of War’, Bloomberg, 24 February 2023, Bloomberg.com.

[2] Apart from that, the West has frozen assets belonging the Central Bank of the Russian Federation worth $300 billion. For more see ‘United Kingdom helps freeze more than £48 billion in Russian assets’, Government of the United Kingdom, 9 March 2023, gov.uk.

[3] ‘Russia’s Tycoons Fear Tightening Kremlin Squeeze as Putin’s War Drags On’, Bloomberg, 14 January 2023, bloomberg.com.

[4] A. Troianovski, I. Nechepurenko, ‘Russian Tycoon Criticized Putin’s War. Retribution Was Swift’, The New York Times, 1 May 2022, nytimes.com.

[5] For more see ‘Trends in Bank Secrecy Act Data: Financial Activity by Russian Oligarchs in 2022’, Financial Trend Analysis, January 2023, U.S. Treasury. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, fincen.gov.

[6] The British government controls the £2.3 billion obtained from the sale of the football club. Since the beginning of 2023, it has worked on devising a mechanism to transfer these funds to Ukraine.

[7] For a ranking of 25 new owners of foreign companies (as at 31 December 2022) see ‘25 новх собственников активов иностранных компаний в России’, Forbes, forbes.ru.

[8] On the battlefield it is impossible to count the pieces of ammunition and military equipment used in detail, or to assess their quality. This creates excellent opportunities to all those who in recent years have been involved in mechanisms for corruption linked to defence procurement; they can adjust the actual size of the stockpile to the financial statements they issued, and thus cover up any traces of corruption in this way.

[9] For more see С. Титов, cooperation М. Маглов, ‘Нетрудовые резервы. Расследование о том, как кланы из окружения Владимира Путина поделили стратегический запас родины’, Проект, 23 January 2023, proekt.media.

[10] In 2021, the value of Russia’s agri-food exports exceeded $36 billion, with grain accounting for a major portion of the goods sold to foreign partners. For comparison, Russia’s armaments exports have been estimated at less than $15 billion.

[11] For more on the Kremlin’s mechanisms to control Russian citizens see M. Domańska, ‘Putin’s neo-totalitarian project: the current political situation in Russia’, OSW Commentary, no. 489, 17 February 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[12] Corruption Perceptions Index, Transparency International, transparency.org.