A ‘key state’: India is gaining significance as a political and economic partner for Germany

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s visit to India in February this year was unlike his other foreign trips. This visit was important not only politically but also economically: the German chancellor was accompanied by managers of companies such as Siemens, ThyssenKrupp, Deutsche Post and SAP. This once again proves Germany’s growing interest in building stronger relations with India. In June 2022, Scholz invited Prime Minister Narendra Modi to a G7 meeting at Schloss Elmau. Only two months earlier, Modi had paid an official visit to Berlin during the sixth bilateral intergovernmental consultations. In February this year, in addition to the chancellor himself, Christian Lindner (FDP) and Annalena Baerbock (Greens) visited India. Their visits were part of meetings of the finance and foreign affairs ministers of the G20 group.

The intensification of Indo-German meetings and bilateral talks is not accidental. German politicians describe India as a ‘key country’ (Schlüsselstaat) on the international arena, and good relations with it are a matter of Germany’s national interest. Thus, this country is becoming one of Germany’s key partners in the process of its adaptation to the intensifying US-Chinese rivalry and its attempts to reduce trade and political dependence on China. At the same time, Berlin’s high expectations regarding enhancing relations with New Delhi are accompanied by concerns about India’s long-term internal stability, the foundations of its economic growth and the state of its democracy.

The international order: shared threats and interests

Germany is increasingly interested in India for a number of reasons. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has deepened Germany’s concern about the polarisation of the world dominated by the confrontation of the two largest powers: the US and China. In order to prevent a ‘new Cold War’, German politicians, in particular those from the SPD, are promoting the concept of a multipolar international order in which regional leaders would gain importance.[1] India is one such regional leader and it has ambitions to play a more important role on the global stage. Enhancing relations with India is also part of the German policy of intensifying activity in the countries of the so-called Global South. The visits of politicians accompanied by delegations of business representatives which took place at the turn of January and February both in India and South America demonstrate this. Other examples include: the strategies adopted by the ministries in charge of foreign affairs and development cooperation addressed to individual regions, and discussions in the Bundestag regarding the creation of new documents of this type.

India has gained importance since the Russian invasion of Ukraine because it may be able to tip the scales in an increasingly divided world. India has decided to remain neutral on this issue and use the situation to benefit economically, including to significantly increase the volume of Russian oil imports. Although Germany would like to convince India to openly condemn the attack on Ukraine, it is not articulating this goal directly. During the chancellor’s visit, the issue of war gave way to the issue of economic cooperation.

Since both countries fear that China’s actions pose a threat to their interests, they may adopt more similar positions in global politics. Berlin is concerned not only about the alliance between Moscow and Beijing becoming closer after 24 February last year, but also about the risks associated with German economic dependence on China.[2] India, in turn, has a long list of border disputes and examples of Chinese provocation, such as giving Chinese names to towns on the Himalayan frontier, which is contested by both countries. Furthermore, the Indian elites are increasingly aware that their homeland may emerge from the shadow of China as a country which already has a larger population, equally high economic growth and, despite many faults, is still a democracy. Improving relations with the West could definitely help India to position itself better against its northern neighbour.

From Germany’s perspective, India is also becoming an important partner in the discussion about the future of globalisation. Germany wants to maintain open trade and curb protectionist tendencies. India is known for protecting its own economy from competition. However, its ambitions for rapid growth and expansion into foreign markets may change its mindset and make it a valuable ally in this regard. For the same reasons, both countries may be interested in strengthening multilateral institutions and international law. One further reason is to prevent the freezing of existing conflicts and the drift towards a new economic ‘cold war’.

The pillars of cooperation: political dialogue and development cooperation

The moves and statements made by the German government so far suggest that it will continue its efforts to strengthen the pillars of political cooperation with India. The first pillar is regular meetings at the highest level. India, along with China and Japan, belongs to a small group of Asian countries with which Germany conducts intergovernmental consultations. Talks in this format take place every two years, and they are interspersed with mutual visits by the German Chancellor and the Prime Minister of India. Bilateral cooperation has been focused on issues such as climate protection, sustainable development, economics and the migration of Indian workers to Germany (since 2010 there has been a sharp increase in their number, and in 2021 there were almost 172,000 Indian citizens in Germany) both during the most recent consultation of this type held in Berlin in May 2022 (the next one is scheduled for 2024 in New Delhi) and during Scholz’s visit to India this year. This is demonstrated by the declarations of intent which were signed at the first meeting covering the areas listed, including the Green and Sustainable Development Partnership, under which the German government has committed to providing almost €10 billion for the needs of bilateral technical and financial cooperation by 2030.

The second pillar is development cooperation. The largest number of German projects in this area (529) are implemented in India, and the sum of funds provided and available to cover them is €5.9 billion. The funds originate primarily from the budget of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and from the state-owned development bank Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) as well as other entities. Last year, BMZ declared it would transfer almost €987.5 million for bilateral development cooperation with India. Germany has thus become the country’s second largest donor of official development aid after Japan. Most projects (155) concern the functioning of the state and civil society, but most of the money goes to initiatives in the field of energy production and renewable sources (€471.5 million) and other infrastructure and social services (€468.2 million).The budget of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action is another source of funds for development cooperation – in 2022 the ministry planned to allocate €37.4 million to cover the costs of bilateral projects in India as part of the International Climate Initiative which is tasked with financially assisting developing countries (according to OECD qualifications) to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Chart 1. Germany’s net official development aid payments to India in 2012–2021

Source: OECD.

Enhancing economic cooperation

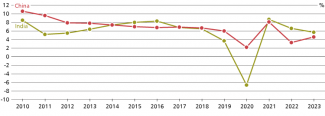

Germany also sees India as an attractive economic partner. Business circles are impressed by India’s rapid GDP growth in recent years (see Chart 2), good demographic prospects and its growing middle class. One of India’s strengths is undoubtedly its cheap and relatively well-qualified workforce, especially in the fields of engineering, information technology and life science. These mean that it is possible to locate both mass industrial production plants and research and development centres there.

Chart 2. Economic growth in China and India in 2010–2023

Source: OECD.

India is also a promising market for Germany’s flagship industries: transport, renewable energy, waste management and environmental protection, as well as the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. It is worth noting that Germany does not only want the expansion of its companies on the local market, but also to attract Indian investments to Europe, for example in the IT and medical sectors. It cannot be ruled out that, given the personnel shortages in Germany, where two million jobs are vacant, Berlin will decide to further facilitate economic immigration, which was already announced in the 2022 agreement. One more reason to build stronger relations with India is Germany’s desire to diversify its economic dependencies. In particular, it is about balancing the position of China, which is becoming an increasingly difficult and inconvenient partner in this area.

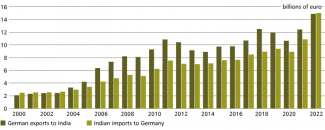

The current balance of Indo-German relations

These strengths are all the more important because the relationship between the two countries so far does not reflect the potential. In 2022, trade reached nearly €30 billion (see Chart 3). Despite a clear increase, this means India only makes it into the top 20 of Germany’s trading partners.[3] In this context, it is worth emphasising that Germany’s trade with China was worth €270 billion in the same year. Germany mainly sells machinery (28%), chemical products (17.5%), aviation industry products (13.3%) and electrical components (8.6%) to India, and buys mainly chemical and pharmaceutical products (24%), clothing (12%) and machinery (11%).[4]

Chart 3. Trade development between Germany and India in 2000–2022

Source: Destatis.

There are about 1,800 German companies operating in India. The automotive sector and the renewable energy sector both have a large representation. The former has BMW, Volkswagen, Daimler (Mercedes-Benz) and Bosch at the forefront. The latter includes Enercon and Siemens, which invest in wind and solar power plants. Chemical companies (such as Bayer, BASF and Merck) and electrical components and industrial automation systems (ABB, Siemens) are also present on the local market. Germany is also expanding its presence in transport. Deutsche Bahn, ThyssenKrupp and Siemens are all investing in India’s infrastructure, including rail and urban transport systems, and have recently had some major successes in this field. Deutsche Bahn won a tender to operate the Delhi-Meerut railway line (900,000 passengers per day) and opened a training centre for train drivers, some of whom may start work in Germany. At the beginning of the year, Siemens received an order worth €3 billion for the delivery of 1,200 locomotives. The defence sector also provides Germany with considerable opportunities. ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems, especially after Modi’s recent talks with Scholz, stands a good chance of winning the tender for the construction of six conventionally powered submarines (around €5 billion). Other weapon manufacturers, such as Renk, also see India as one of the most important arms buyers in the near future.

In recent years, investment capital has also started to flow in the other direction. This has translated into a growing presence of Indian companies on the German market. These include the ArcelorMittal steel production corporation, the Tata Group conglomerate which operates in IT, consulting, steel and engineering industries (and others), as well as Aditya Birla Group (packaging). The IT sector, led by the global brands Wipro and Infosys, also has a good position. Companies from the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors, such as Rain Industries and Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, and the automotive industry, such as Samvardhana Motherson and Apollo Tyres, are expanding to Germany with increasing confidence. Indian capital is also interested in renewable energy, one proof of which is the activity of the Adani Group.[5]

Problems with cooperation

The enormous potential and promising prospects of the two countries’ improving relations do not eliminate uncertainty about the future. Berlin is concerned about the problems of Indian democracy, in particular the Modi government’s increasing influence over the media, the repression of opposition politicians and the growing nationalism that is polarising a multicultural and multi-ethnic society. The system is also facing the problem of rising oligarchy. The scandal over the influential Adani Group, which lost $100 billion on the stock exchange after a critical report by American investors, was considered a warning in this context. Therefore, despite Germany’s hopes, it is not a foregone conclusion that India will become a stable and predictable partner for the West in the escalating confrontation between democracies and autocracies.

There are also concerns about the development prospects of the Indian economy. According to economist Ashoka Mody, author of the widely cited book India Is Broken, expectations that the country will be a ‘better China’ are groundless, as they are based mainly on data from the post-pandemic recovery, not on India’s structural characteristics.[6] This especially concerns the underdeveloped infrastructure, low quality of regulations and corrupt bureaucracy; German business has faced all of these for a long time. The legislative and cultural differences between the individual states of India increase management costs, which is also an issue. These doubts seem to be confirmed by e.g. Apple’s experience. Apple, along with its supplier Foxconn, decided to quickly transfer some phone production from China to India. Now it seems to have serious problems with the quality of devices manufactured in Indian plants.

In the opinion of many entrepreneurs, the seriousness of the above-mentioned factors may outweigh such advantages as low labour costs. In a survey carried out by the consulting company KPMG and the German-Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, as many as 59% of companies complained about administrative barriers related to obtaining licences, access to public tenders or the requirement to order semi-finished products from local suppliers. More than one third pointed to corruption, a complicated tax system and an unstable legal system as significant obstacles in running a business. German entrepreneurs are also worried that, despite India’s global ambitions, its government is still inclined towards protectionist practices. The Indian government’s decision in early February this year to raise tariffs on cars and scooters, which had already been relatively high compared to prices in other countries, provoked a great deal of controversy. Therefore, there is little hope for rapid progress in the negotiations concerning the long-awaited trade agreement with the EU.

Therefore, some inconsistency can be expected in Germany’s policy towards India. On the one hand, the government and its agencies will strive to tighten economic and political cooperation with India and to diversify global ties. On the other hand, business will remain quite conservative and will continue to favour the predictability of authoritarian China over promising but uncertain Indian development.

[1] See L. Gibadło, ‘Kierownictwo SPD o polityce zagranicznej: przywództwo RFN w multipolarnym świecie’, OSW, 14 February 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[2] Idem, ‘A dangerous resemblance. Moves to revise Germany's China policy’, OSW Commentary, no. 473, 19 October 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[3] ‘Rangfolge der Handelspartner im Aussenhandel’, Statistisches Bundesamt, 13 April 2023, destatis.de.

[4] ‘The History and Future of Indo-German Trade’, Deutsch-Indischer Handelskammer, 8 September 2022, indien.ahk.de.

[5] Based on: ‘Die deutschen Unternehmen in indischem Besitz’, Die deutsche Wirtschaft, 4 May 2022, die-deutsche-wirtchaft.de.

[6] A. Mody, India Is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today, Stanford University Press, 2023.