Ukrainian oligarchs and their businesses: their fading importance

The longer Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine continues, the weaker the oligarchs’ influence on the country’s political and economic life becomes. They have failed to regain control over media coverage and have little to no sway over parliament. Their businesses have suffered heavy losses as a result of the hostilities and the economic crisis. Consequently, the estimated wealth of many oligarchs has more than halved. In addition, the state has taken numerous steps aimed at representatives of big business, including the nationalisation of some of their assets. This trend will persist as long as the active phase of the war continues. However, it is too early to say that the decline of the oligarchs is permanent.

The impact of the war and the economic crisis on the oligarchs’ businesses

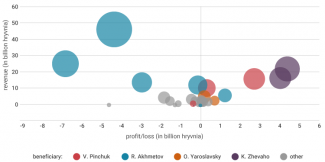

The Russian aggression has caused an economic collapse in Ukraine (its GDP fell by 29.1% in 2022 and by 13.5% in the first quarter of 2023)[1] and had a negative impact on the health of local businesses, including those owned by the oligarchs. These losses have not been spread evenly: they have depended on geographical location (factories in areas where clashes were or are ongoing have suffered the most) and the business sector concerned. Another significant factor is the degree to which production had been oriented towards exports, which before the war were largely carried out by sea. Since last August, Ukrainian ports have been partly unblocked as part of the so-called ‘grain corridor’, but only certain categories of agricultural products (mainly cereals, oilseeds and oils) are being exported via this route, in contrast to industrial goods, particularly steel products and iron ore. Indeed, the steel industry has been most affected, mainly because the maritime blockade has significantly reduced access to production outlets and forced Ukraine to search for land routes across its borders with the EU. As a result, the value of metallurgical exports fell by 62.4% in 2022 (from $16bn to $6bn) and their share in the country’s total foreign sales decreased from 23.5% in 2021 to 13.6% the following year.

Another challenge came with the frequent nationwide electricity blackouts from October 2022 to March 2023, which were caused by Russian strikes on Ukrainian energy infrastructure. In some cases, production was mainly affected by direct fighting. The Metinvest group, which is owned by the country’s richest oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, suffered particularly badly: its two metallurgical plants in Mariupol were destroyed, and the companies that comprise the group recorded a total loss of $2.2 billion in 2022, compared to a profit of $4.7 billion the previous year. Production of cast iron and steel at Metinvest’s plants fell by 72% and 69% respectively last year.[2] The entities owned by Viktor Pinchuk were in a slightly better situation as they are located in the Dnipropetrovsk region, somewhat further from the front line. It is worth noting that these problems were not exclusive to the oligarchs’ businesses: for example, ArcelorMittal’s smelter in Kryvyi Rih recorded a loss of around $1.3 billion in 2022.

Chart 1. Financial performance of companies in the metallurgical sector in 2022

Source: the author’s own compilation based on data from opendatabot.ua.

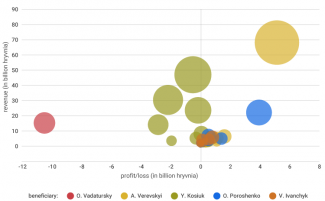

Agriculture has been much less affected by the war, although some assets and land have also been lost in this sector[3] after they came under Russian occupation. Last April, the agricultural sector’s direct losses as a result of the armed conflict were estimated at $8.7 billion, including $4.7 billion in equipment and another $1.9 billion in grain storage facilities.[4] In July 2022 Oleksiy Vadatursky, the owner of Nibulon, one of the country’s largest grain producers and exporters, was killed in a Russian missile strike. His holding company has suffered enormous losses as its headquarters is located in Mykolaiv, a city that was heavily damaged in shelling, while a large part of that company’s elevators are located in the city’s harbour, which has not been included in the so-called grain corridor.

Nonetheless, most of the large agricultural companies have reported good financial results (see Chart 2). This is particularly true of the companies owned by Andriy Verevsky. Kernel, Ukraine’s largest sunflower oil producer and exporter, which is listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, made a profit of more than $140 million last year. This most likely stemmed from the fact that oils cost more than grain, so the large export-related logistics costs are not so important in this case. The entities managed by Petro Poroshenko (formally registered to his son Oleksiy) also closed 2022 in the black.

Chart 2. Financial performance of food and agriculture companies in 2022

Source: the author’s own compilation based on data from opendatabot.ua.

Despite the relatively good performance in 2022, the agro-barons are highly unlikely to fare as well in the current year, as grain prices have been falling steadily over the past 12 months. In addition, on 2 May an EU ban on the imports of Ukrainian grain and oilseeds came into effect; this covers five EU member states (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria) which became important recipients of these commodities last year. The ban is set to remain in place until 15 September, but it may be extended. The next problem concerns the sustainability of the so-called grain corridor, which is the current route for the bulk of Ukraine’s agricultural exports. Russia has repeatedly threatened to tear up the grain deal and has artificially extended cargo inspections, which has pushed up transport costs and consequently reduced the profitability of foreign sales. Finally, mines and unexploded ordnance are making cultivation difficult or even impossible in the liberated areas and those situated close to the front line. The Ukrainian government has estimated that the available crop area will decrease by 7 million ha in 2023 compared to 2021,[5] which will certainly affect exports.

Selected oligarchs and their problems

The economic crisis is not the only challenge facing the oligarchs. In recent months, the government has taken numerous measures against this group, including the nationalisation of some of their assets. Paradoxically the oligarch most affected is Ihor Kolomoisky, who was considered close to President Volodymyr Zelensky during the first phase of his rule. The media owned by Kolomoisky supported Zelensky’s election campaign and then his policies. Dark clouds began to gather over the oligarch back in 2021, when the US imposed sanctions on him. In July 2022, Zelensky signed a decree that stripped the businessman of his Ukrainian citizenship, which in theory opened the way for his extradition to the United States, where he is facing money laundering trials.[6] Last November, the National Commission on Securities and the Stock Market decided to hand over Ukrnafta and Ukrtatnafta (in which Kolomoisky formally held a minority stake, but he de facto controlled them through the management board) to the State Treasury because of their importance for the war effort: Ukrnafta owns the largest network of petrol stations in the country and is also a leader in oil production. Although the government has said that these assets could be returned or compensation could be paid after the war ends, it is difficult to say whether this will actually happen. Furthermore, Kolomoisky has lost control of Dnipro airport (in September 2022, following a verdict by an administrative court) and Ukrnaftoburinnia (last April), one of Ukraine’s largest natural gas producers, which he managed together with fellow oligarchs Pavel Fuks and Vitaliy Khomutynnik. Kolomoisky is facing multiple investigations, including into financial crimes at Ukrnafta and purchases of underpriced electricity.[7]

Kolomoisky is not the only oligarch whose assets have been seized by the state. In May 2022, more than half of the companies involved in regional gas distribution were taken over at the request of the State Bureau of Investigation. This step was formally justified by their debts related to the use of gas pipeline networks.[8] The largest player in this segment of the market (around 70%) is the Regional Gas Company linked to Dmytro Firtash, a pro-Russian oligarch who has been under house arrest in Austria since 2014 at the request of the US, which has charged him with corruption. More than a year has passed since then, but the state has still failed to gain effective control over the nationalised entities.[9]

Criminal cases against Kostyantyn Zhevaho (a businessman whose most important assets are concentrated in the iron ore mining industry) and Oleh Bakhmatiuk (the food and agriculture sector) can be seen as other examples of actions targeting oligarchs. Both of these cases are the culmination of proceedings that began back in 2014–15 and are related to financial crimes in the banks they owned: Finance and Credit (which went bankrupt in 2014) and VAB (which filed for bankruptcy in 2015). International arrest warrants have been issued for the two oligarchs. Zhevaho was detained in France in December 2022, but the local court has refused to extradite him. A court in Vienna has taken the same decision with regard to Bakhmatiuk.

It is difficult to say conclusively why the state has been targeting some oligarchs while staying neutral towards others. The nationalisation of some of Kolomoisky’s assets may have stemmed from the fact that he has failed to condemn Russian aggression and given little support to the Ukrainian armed forces. This attitude sets him apart from the likes of Akhmetov, Poroshenko and Pinchuk, all of whom have been actively helping the defenders through their foundations. Moreover, Pinchuk continues to support the country in the international arena: for example, he organised the Ukrainian Lunch at the Munich Security Conference.

The implementation of the anti-oligarchy law has been frozen

De-oligarchisation was one of the slogans used by the presidential camp in the final months before the outbreak of the war. In September 2021, the parliament passed the so-called law on oligarchs, which targeted individuals who met three of the following four conditions: participation in political life, influence over the media, a dominant position in a particular sector of the economy, and assets worth more than $90 million. The act provided for the creation of a special register that would include people recognised as oligarchs by the National Security and Defence Council (NSDC). According to its secretary Oleksiy Danilov, the list could have included 86 names. Certain restrictions (including a ban on participation in privatisation) and an obligation to submit an annual declaration of assets will be imposed on entrepreneurs who are recognised as oligarchs.[10] The register was originally due to have been created by April 2022, but the outbreak of the war delayed these plans. In January 2023 Andriy Yermak, the head of the President’s Office, said that the list would be drawn up, but the state currently has other priorities. In February 2023 the government adopted a decree which stipulated that the list would be prepared within three months of receiving an opinion from the Venice Commission; on 9 June the Commission recommended that the implementation of the law be postponed until after the war. At the same time, it is one of the European Commission’s seven recommendations whose fulfilment will make it easier for Ukraine to start accession negotiations with the EU. However, the mere possibility of being included on the list of oligarchs has led to some changes. The former president Petro Poroshenko has formally divested his media assets, Akhmetov closed down his TV channels and websites in July 2022, while Vadym Novynskyi (his partner in the metallurgical sector) has resigned as a deputy of the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian parliament) so as to avoid meeting the criterion of having political influence.

The prospects for the oligarchic system

In the short term, the reversal of the downward trend in the importance of the oligarchs that has been seen since the outbreak of the war is likely to continue. There are several reasons for this. The government is unlikely to cede its control over media coverage to the owners of television channels until the period of martial law ends. Previously, this was one of the most important tools by which big business influenced government officials and, more broadly, political life in the country. Nor should we expect the strong economic growth that would boost the revenues of the companies owned by the oligarchs. The latest forecasts from the National Bank of Ukraine forecast growth of 2% in 2023 and 4.3% the following year. This means that the financial situation of most companies will remain difficult. This is particularly true of metallurgy, as exports by sea, which would make it possible to increase production, appear unlikely to be unblocked before the end of the war. It is also an open question as to whether the losses incurred will sooner or later lead to a wave of bankruptcies, especially as a significant number of companies are struggling with debt (for example, Metinvest’s debt stood at $1.7 billion in 2022) and will find it increasingly difficult to settle their liabilities. For the time being, these are isolated cases (bankruptcy procedures have been initiated by three plants in Mariupol owned by Akhmetov: Azovstal, Ilyich Works and the Mariupol Mechanical Repair Plant), but the longer the fighting drags on, the more such cases we will see.

The influence of big business is also limited by the fact that the Ukrainian government is entirely dependent on financial assistance from the West, which runs to tens of billions of dollars a year (excluding military support) and de facto underpins the functioning of the state. Therefore, the real influence of donors on the government in Kyiv has increased markedly since 24 February 2022; consequently, the relative importance of the domestic barons and their influence on state policy-making has been diminishing.

However, it is extremely difficult to forecast how the position of the oligarchs will change in the longer term after the hostilities come to an end. If the most optimistic scenario for Ukraine (wherein it achieves peace and maintains its sovereignty) comes true, representatives of big business will be unlikely to reclaim their status in the country. They might succeed in regaining control of the media and securing some influence over the Verkhovna Rada, but at present it is impossible to predict the composition of the parliament after the elections, which can only take place after martial law has been lifted. Given some progress in the fight against corruption in recent years and the weakening of the oligarchs as a result of the war, it seems unlikely that puppet factions controlled by big business will emerge in the Verkhovna Rada as they did before the invasion. Nevertheless, the fight against informal oligarchic influence and, more broadly, bribery is a long and complicated process, which requires sustained pressure from the public, the media and the international community.

European integration could save Ukraine from a return to its pre-war practices. This process will be spread over many years, and will require the government in Kyiv to continue reforming the state in accordance with EU standards, which should reduce oligarchic influence on the country’s political and economic life. This could be facilitated by the inflow of foreign capital, which may help to break up existing monopolies and boost market competitiveness. Such developments were already taking place before the Russian aggression: according to calculations by the Centre for Economic Strategy, between 2010 and 2020, the share of the 20 largest business groups in terms of assets fell from 15% to 10–12%, and in terms of employee numbers from 8% to 5%.[11] Moreover, businessmen from other sectors, such as agriculture, retail and IT, have increasingly featured in the rankings of the richest Ukrainians alongside the ‘old’ oligarchs such as Akhmetov, Pinchuk and Kolomoisky. Post-war reconstruction, coupled with major economic restructuring, will entail the development of new industries and a relative decline in the importance of those sectors which have traditionally had a strong oligarchic presence (primarily heavy industry).

At the same time, there is a risk that the process of rebuilding the country, which will involve funds running into the billions (though it remains unclear where these funds will come from), may spawn new oligarchs who will make money from state-awarded contracts.[12] Indeed, the government may be tempted to create a class of state-dependent businessmen. It remains an open question whether it will succeed in this.

[1] А. Жарикова, ‘Падіння реального ВВП у І кварталі уповільнилось 31,4% до 13,5% – Нацбанк’, Економічна правда, 5 May2023, epravda.com.ua.

[2] Д. Чепур, ‘Група «Метінвест» прозвітувала про збитки у понад $2 млрд за 2022 рік’, Forbes, 31 March 2023, forbes.ua.

[3] For more on the health of the agricultural sector, see S. Matuszak, ‘Agricultural production in Ukraine has declined significantly’, OSW, 27 February 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[4] ‘Збитки агросектору та земельним ресурсам України від повномасштабної війни складають $8,7 млрд’, Київська школаекономіки, 19 April 2023, kse.ua.

[5] S. Matuszak, ‘Agricultural production in Ukraine has declined significantly’, op. cit.

[6] Idem, ‘Amerykańskie uderzenie w Kołomojskiego’, OSW, 9 March 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[7] ‘САП завершила розслідування продажу електроенергії "Енергоатома" Коломойському за зниженою ціною’, Бізнес цензор, 4 May 2023, biz.censor.net.

[8] І. Орел, ‘Коло замкнулося. Навіщо держава забирає у Фірташа облгази і повертає собі монополію на ринку розподілу газу’, Forbes, 26 May 2022, forbes.ua.

[9] О. Чайка, І. Орел, ‘Дмитро Фірташ VS «Нафтогаз». Чому націоналізація облгазів мультимільйонера йде зі скрипом’, Forbes, 16 March 2023, forbes.ua.

[10] S. Matuszak, ‘An attempt to “deoligarchise” Ukraine – real action or a game of pretence?’, OSW Commentary, no. 415, 15 November 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[11] Д. Горюнов, ‘Реєстр олігархів на паузі. Чи послабить це тиск на найбагатших?’, Forbes, 13 March 2023, forbes.ua.

[12] M. Champion, D. Krasnolutska, ‘Ukraine Has Decimated Its Oligarchs But Now Fears New Ones’, Bloomberg, 6 April 2023, bloomberg.com.