A shadow budget. Germany increases spending through special funds

Germany has found itself in a stalemate between its strict budgetary rules and the need to fight the economic crisis, cushion rising energy costs and earmark more funds for public investment. To tackle this challenge, it has decided to boost the role of special funds, which have been increased by way of temporarily suspending the constitutional ‘debt brake’ and changing the procedures for reporting new debt. This will allow the government to spend additional tens of billions of euros annually on selected projects, while declaring compliance with the restrictions enshrined in the Basic Law. Although this solution guarantees relative political tranquillity within the coalition led by Olaf Scholz, it raises numerous legal doubts because it is viewed as an attempt to circumvent the ‘debt brake’. Furthermore, the decision to increase spending outside the federal budget will make Germany’s actions at the EU level more difficult, as it will undermine the credibility of its efforts to convince other member states to put their public finances in order.

The parties making up the government in Berlin have been engaged in a dispute over the direction of Germany’s economic policy. The SPD and the Greens believe that increasing the state’s investment spending in strategic areas is key to fostering growth, which is necessary because in this area private business is not fast enough and works on too small a scale. The liberal FDP, on the other hand, intends to reduce the tax burden and to encourage private investment through special reliefs. In this party’s opinion, the government should focus on devising the appropriate regulatory framework rather than on interfering in the market mechanism.

This dispute has been exacerbated during the pandemic and the crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine, during which pressure to boost the role of the state in the economy has generally increased. From the FDP’s point of view, the ‘debt brake’ (Schuldenbremse, SB), which is enshrined in Article 115(2) of the Basic Law, has become the key mechanism for blocking interventionism. According to this provision, new federal budget debt must not exceed 0.35% of Germany’s GDP annually. Deviations from this rule are only allowed in extraordinary circumstances; one such involves a difficult economic situation in which negative economic prospects push expenditure above the limit, albeit according to a strictly defined algorithm. Another such circumstance is a natural disaster or other emergency situation in which the debt brake can be temporarily suspended by a resolution passed by the Bundestag. This option was used in 2020–2, when the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent energy crisis paralysed the economy (see Chart 1). When the wave of the crisis began to subside, the political battle to reinstate the restrictive regulation flared up again.

Chart 1. Germany’s quarterly GDP dynamic in 2019–2023 (change versus the preceding quarter)

Source: Eurostat.

The return of the ‘debt brake’

Christian Lindner, Germany’s finance minister and leader of the FDP, has argued that the spending cap could help to reduce high inflation rate; in November 2022 the HICP rate stood at 11.6%. In addition, limiting public demand for debt could result in lower interest rates and reduce the so-called crowding out of private business from the capital market by the state. This, in turn, is intended to create better conditions for investment growth in this sector. Moreover, in a clever move Lindner also referred to German society’s profound conviction that it is necessary to reduce debt and ensure fiscal stability. The argument that Germany should return to ‘healthy’ economic management once the big anti-crisis programmes are finished, including to the principle according to which any increase in spending should be offset by higher revenues or savings (Article 110(1) of the Basic Law), may have been targeted at conservative voters in particular.

Ultimately, the minister did achieve his goal: the coalition partners agreed to reinstate the ‘debt brake’. Although the 2023 budget included the requirement to respect the new debt limits, the scope of spending was slightly increased due to the difficult economic situation. At first glance, it seemed that the reinstatement of the constitutional rule was the result of a successful campaign, as well as proof of the finance minister’s political acumen. However, the real explanation is more complex: the compromise in the coalition would not have been possible without the intricate financial engineering which has enabled the government to increase spending ‘beside’/‘in parallel with’ the fiscally constrained main budget. This was possible due to the institution of so-called special funds, Sondervermögen (SV).

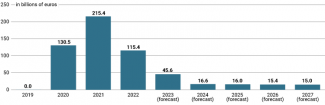

Chart 2. The federal budget’s net new debt in 2019–2027

Source: M. Greive, J. Hildebrand, ‘Haushälter fürchten die härtesten Etat-Verhandlungen seit Jahren’, Handelsblatt, 25 September 2023, handelsblatt.com.

The shadow budget

Special funds are not a novelty in German public finance. They are envisaged/provided for in the constitution (Article 110(1)), and the oldest such funds were established as far back as the 1950s. From the legal point of view, they are separate funds created by way of enacting a special law (or on the basis of such a law) to meet special needs and spending objectives such as post-war reconstruction, reunification, and the challenges posed by the transformation of specific sectors of the economy. In formal terms, they are subject to the same rules as the federal budget, but are managed and accounted for separately. They can be funded from budget subsidies or from their own resources and, if permitted by the law, also from loans taken out by them, which are included in the public debt. At present, Germany has 29 such funds, and the total budget of the largest, those which have at least €1 bn at their disposal, is more than €869 bn.

The recent crises and investment needs have contributed to what the Federal Court of Audit has referred to as “an unprecedented increase and expansion” of the SV.[1] The Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF) established in 2011, the Economic Stabilisation Fund-Corona (WSF-Corona) created in 2020, and the Bundeswehr Special Fund (Sondervermögen Bundeswehr) and the Economic Stabilisation Fund – Energy Crisis (WSF-Energiekrise), which were established in 2022, have a total of around €555 bn at their disposal (see Table).

Table 1. Special funds authorised to incur debt

Source: Federal Court of Audit.

Today, it is difficult to imagine Germany carrying out the state’s tasks without the SV. According to the Federal Court of Audit, expenditure incurred by the 13 funds included in the government’s spending plan for 2022 accounted for 10% of budgetary spending (€48.2 bn). In the 2023 spending plan, the proportion had risen to 35.9% (€170.9 bn).

The importance of the SV is also evident in the figures for net new debt (Nettokreditaufnahme, NKA) reported at the federal level. In 2022, the SV accounted for as much as €80.1 bn out of the €195.5 bn reported as NKA. In the 2023 figures, this proportion has increased significantly: out of the total net new debt sum of €192.8 bn the special funds account for €147.2 bn, while the federal budget, now with the reinstated ‘debt brake’, accounts for just €45.6 bn. This indicates that the debt generated by the SV is more than four times bigger than that generated by the regular budget (see Chart 3).

Chart 3. Germany’s net new debt in 2022 and 2023

Source: Federal Court of Audit.

Circumventing the ‘debt brake’

Given the huge increase in the value of the SVs, the question of their relationship to the restrictive rules which govern German public finances should be raised. In this context, it should be noted that when the ‘debt brake’ was introduced, it was assumed that the special funds were taken into account when calculating the limits on new debt in the financial year. This means that their finances and those of the regular budget were consolidated, and any shifts between them were in fact irrelevant. If an SV had a negative balance, the difference had to be offset either by transferring funds from the federal budget (which consequently showed a higher debt) or by directly incurring a liability which was subsequently taken into account in the calculation of the ‘debt brake’.

These rather simple principles were challenged during the pandemic, when the government suspended certain fiscal restrictions. Although at that time it was authorised to incur an enormous debt, in practice it could not use this competence because the planned debt was simply too big for the needs of the anti-crisis policy. As a consequence, this pool of funds found itself suspended in a spending vacuum, and formal measures were taken to cancel it, but at the same time the temptation arose to spend it on other politically important purposes endorsed by the government.

The first move to achieve this was made in 2020, when borrowing rights worth €28 bn intended for the anti-crisis policy were reallocated for other purposes. This raised doubts because suspending the ‘debt brake’ did not mean that the extra funds could be spent freely. A year later, although the government was authorised to incur a debt of up to €240 bn to combat the pandemic, it only used €180 bn out of this sum. As a consequence, last year’s move was repeated: instead of using up the remaining funds, the coalition decided to re-allocate €60 bn to the Energy and Climate Fund (Energie- und Klimafonds, EKF), which in the meantime was renamed to the KTF. It was intended to finance the construction of electricity grids, the development of the hydrogen economy, electromobility projects etc. This is how a short-term intervention to fight the crisis was transformed into a long-term structural budget.[2]

In the shadow of the multi-billion transfers, in 2021 another change was made which can undoubtedly be viewed as systemic in nature. This concerned the rules for accounting. The consolidation of the annual balances of the federal budget and the SV budgets was abandoned, and instead the flows between them began to be accounted. Effectively this meant that the government was able to transfer large borrowing rights to the SV, and at the same time it cancelled the requirement according to which the borrowed funds had to be spent within a given financial year. To justify the new mechanism, the government cited difficulties in devising spending plans in the unstable situation linked with the crisis. This unsophisticated explanation was intended to conceal a fundamental change: the government was now able to suspend the ‘debt brake’ to feed the SVs, and to spend this money in a discretionary manner over subsequent years.

The constitutional complaint

This practice has sparked immense controversy among lawyers and financial law experts. The reaction from the Federal Court of Audit was particularly harsh because this office had repeatedly pointed to the discrepancy between the solutions adopted and the logic of the budget control rules which had been shaped over several decades.[3] The parliamentary opposition joined in this criticism: in April 2022 197 MPs from the CDU lodged a complaint about the government’s actions with the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe. In their opinion, the borrowing rights should have been used solely in connection with the pandemic, as this was the reason why the ‘debt brake’ had been suspended. Shifting these funds to other spending categories and beyond the timeframe of the currently valid financial plan – in this case for the purpose of funding the energy transition – was unlawful, and any investments in this field should have been funded from the regular budget. The coalition refuted the accusations, saying that the spending shifts were in fact an element of a broader plan involving the fight against the consequences of the pandemic.

The first stage of the dispute ended in a victory for the government. In December 2022, the justices issued an initial verdict in which they supported the arguments presented by the finance ministry. Despite this, the Federal Constitutional Court highlighted several important issues which will be analysed during the main proceedings, and the final verdict may not be favourable to the government. This for example may involve democratic control of the funds transferred from the budget to the SVs, as well as a more precise definition of the term ‘emergency situation’ which forms the basis for suspending the ‘debt brake’.

A fragile political truce

The legally controversial expansion of the special funds, which are often referred to as a ‘shadow budget’ (Schattenhaushalt), is the price for maintaining the stability of the ruling coalition. The FDP intends to demonstrate to its supporters that under Lindner Germany is returning to its ‘debt anchor’. The economy will receive support in the form of SVs devised ‘with precision’ as well as the recently enacted law on development prospects, which offers tax incentives to companies to increase their investment spending. The Greens and the SPD, for their part, are now able to praise the government’s activity and highlight the multi-billion sums earmarked for the energy transition, digitisation and public investments which are available from the extra-budget funds.

However, the processes which have been triggered may undermine the political consensus. Should the economic situation continue to deteriorate, pressure to further boost public spending will increase. Ricarda Lang, co-leader of the Greens, has proposed setting up government funds which would be independent of the budget to carry out important public tasks. The SPD, for its part, would welcome a separate pool of funds earmarked for climate protection, with its own borrowing rights. The fact that this manner of thinking about the future of public finances has become increasingly popular is also evidenced by the demands voiced by teachers and caregivers during the protests held in September regarding the creation of a special fund for the education sector. The proposed €100 bn fund could be spent on investments in schools and kindergartens and on staff training.

Minister Lindner has attempted to curb these expectations: in his budgetary plans he highlighted his intention to gradually reduce the role of the SVs, although for the time being he intends to achieve this by shifting several small funds to the federal budget. The FDP leader is aware that the combination of the poor economic situation and a growing appetite for spending may ultimately result in the validity of the ‘debt brake’ being put on the political agenda. Starting from 2028, the need to repay the loans taken out to fund the SVs will further exacerbate the problem. Combined with the debt linked with the European recovery fund, this means that the German state budget will need to generate an additional sum of almost €20 bn annually for this purpose. This is not the only source of tension: the current debt servicing cost has increased, and the federal government has ceded numerous taxes and levies to the federal states and local governments, which limits its capabilities to generate higher revenues.[4]

This means that the SPD and the Greens are now in a position to increase their pressure to reform the ‘debt brake’. Some economic analyses support their stance. For example, according to the German Economic Institute in Cologne, which is associated with employers’ organisations, gradually releasing the ‘debt brake’ and increasing the budget deficit to 1.5% of Germany’s GDP will not increase the public debt; on the contrary, it could even reduce it from the present 66.3% (2022) to 61.2% in 2030. This solution could enable Germany to increase its spending by €44 bn in 2023.[5]

The European consequences of the SV’s expansion

The German government’s financial engineering may also trigger serious consequences at the EU level. For years, Germany has been committed to introducing a tough fiscal policy regime based on clear rules in order to force the indebted southern EU member states to save money and increase the transparency of their public finances. This idea was behind the introduction of the Stability and Growth Pact back in the late 1990s, which set nominal limits of 3% on the budget deficit and 60% on public debt. As part of further reforms, a requirement was added for budgets to be balanced in the medium term, which means that deficits accumulated in less economically favourable years should be ‘repaid’ using surpluses recorded in times of prosperity. To achieve this, measures such as the medium-term structural balance criterion were introduced. This was intended to present the state of public finances once ‘cleaned’ of the impact of the economic situation and one-off factors: the finances should in general be balanced or almost balanced. In 2009, as Europe was plunging into economic collapse, Angela Merkel’s government ostentatiously introduced a ‘debt brake’ to motivate other countries to copy the German model of the ‘culture of stability’. In 2012, a fiscal compact was agreed which committed EU member states to introduce strict fiscal regulations. This was also when Germany saw the beginning of the ‘black zero’ era, linked with the budget surpluses which the government boasted about at the EU level.

The crises triggered by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have forced the EU to suspend the rules of fiscal discipline and consent to higher government spending. As a consequence, 2019–22 saw an overall increase in public debt in relation to the GDP, despite the fact that a high inflation rate usually causes this ratio to decline (see Chart 4). Officially, Germany has called for a gradual return to a prudent fiscal policy. This is also why it opposes the European Commission’s proposed reform of the Stability and Growth Pact, which intends to increase flexibility as regards debt reduction paths and to foster an increase in public spending on development investments. At the beginning of October 2023, Lindner rejected another proposal put forward by the Spanish presidency of the EU Council, which suggests that a compromise should not be expected any time soon.

The practice applied by the ruling coalition has weakened Germany’s arguments in favour of a technocratic fiscal regime which is based on clear rules and encourages prudence. While the finance minister will try to focus the debate on the nominal convergence criteria, which also relate to the SVs, he will need to face the question of how to promote investment in crucial times for the EU. If, despite its relatively small debt, Germany has to resort to dubious tricks, how are countries such as Italy, Greece and Spain supposed to tackle this challenge? Therefore, as Germany’s opponents will argue, two options will need to be considered: the first one involves easing the fiscal restrictions, and the other involves creating a common European strategic investment fund. For the time being Berlin does not support either option; however, the political cost of its ongoing blockade will keep rising.

Germany’s EU partners have yet another reason to criticise the federal government’s increased spending via special funds. Past experience has shown that these are sometimes used in an arbitrary manner, and therefore may be employed to improve the situation of German companies at the expense of their European competitors (for example, subsidising the energy prices) and to finance incentives for foreign investors. Many EU member states are unable to compete with Germany in the field of subsidies, even if they wanted to, because of their own high sovereign debts. Others view such practices as a manifestation of an expansion of interventionism, which spoils market economy mechanisms. Others believe, and this is probably the most apt argument, that in the present circumstances, Berlin’s actions may jeopardise European cohesion because they come dangerously close to the boundary of unauthorised state aid and the infringement of the integrity of the EU’s single market.

Chart 4. Relation of public debt to the GDP in EU member states in 2019 and 2022

Source: Eurostat.

[1] Bericht nach § 88 Absatz 2 BHO an das Bundesministerium der Finanzen über die Sondervermögen des Bundes und die damit verbundenen Auswirkungen auf die Haushaltstransparenz sowie die Funktionsfähigkeit der Schuldenregel, Bundesrechnungshof, 25 August 2023, p. 2, bundesrechnungshof.de.

[2] T. Büttner, ‘Not kennt kein Gebot. Sondervermögen als Speicher von Notlagenkrediten’, Wirtschaftsdienst, 2022, wirtschaftsdienst.eu.

[3] For an exchange of arguments with the Federal Ministry of Finance see Bericht nach § 88 Absatz 2 BHO…, op. cit.

[4] D. Christofzik, ‘Haushaltsspielräume des Bundes: Strukturelle Schieflagen lösen sich nicht durch Aufschieben’, Wirtschaftsdienst, 2023, wirtschaftsdienst.eu.

[5] M. Beznoska, T. Hentze, K. Rietzler, M. Werding, ‘Herausforderungen für nachhaltige Staatsfinanzen’, IW-Trends Forum 3/2023, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln, iwkoeln.de.