Fighting ‘hostile’ memory: the vandalism of Polish monuments in Russia

In 2023, Russia has seen a spike in acts of destruction or removal from public space of monuments and symbols commemorating the victims of political repression, primarily Poles. This is connected with Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine as well as the explicit designation of Poland by the Kremlin and in Russian propaganda as a hostile state. Local authorities tend not to react to any damage or desecration of memorial sites: in most cases they have failed to launch investigations or track down the ‘unknown perpetrators’. It remains an open question to what extent these acts of vandalism have been inspired by officials or initiated by nationalist-imperialist circles, but such actions are consistent with Russia’s long-standing policy of cultivating the ‘historical truth’ in the spirit of glorifying state terror and imperial expansion.

The war on monuments

Since autumn 2022, independent Russian media outlets and activists from the Memorial association have reported an increase in the number of acts of vandalism (destruction or dismantling) targeting sites commemorating the victims of political repression, mostly Poles and less frequently Lithuanians or Ukrainians. There have also been reported cases of removals of monuments commemorating Finnish soldiers who were killed during World War II. In total, at least 15 monuments and commemorative plaques have been removed or vandalised (see Appendix for details). These figures are incomplete as some of these sites are located deep in the interior of the country, and the reports on their status arrive only after some delay.

In parallel with these acts of destruction of sites commemorating persecuted Poles, there has also been a spike in removals of the ‘Last Address’ plaques that have been installed as part of a campaign launched in 2014 to commemorate the victims of Stalinist repression by placing small metal memorial plaques on the houses from which they were taken ‘on their last journeys’. In addition, Moscow’s city government has denied permission to hold the Restoring Names event commemorating the victims of Soviet repression at the Solovetsky Stone on 29 October, for the fourth year in a row.

It is notable that the regime has neither openly encouraged nor publicised such acts of vandalism for its propaganda purposes, for example as part of its campaign against the ‘enemies of Russia’. Local officials and law enforcement agencies have repeatedly denied responsibility for such incidents, while remaining passive and demonstrating no interest in finding the ‘unknown perpetrators’.

So far, there have been no signs of any large-scale coordinated action targeting the monuments to Soviet victims of repression, but such a scenario cannot be ruled out in the future. Indeed, it is in the government’s interest to erase the memory of the history of state terror in view of the escalating political persecution in Putin’s Russia. Moreover, as the space for anti-war and anti-regime dissent has shrunk to almost zero, such monuments have often become sites for grassroots-led, spontaneous micro-protests against the war or in defence of political prisoners.

An Orwellian politics of memory

Regardless of whether the vandalisation of monuments occurs on the initiative of local authorities, including security forces, or as a result of grassroots actions by local groups of ‘ultra-patriots’, such acts have been taking place against the backdrop of the decades-long build-up of consent to, and even encouragement of, the destruction of any historical memory that runs counter to the Kremlin’s official narrative. The Russian government has never been interested in the systematic commemoration of the victims of state violence: most of the memorials erected since the late 1980s have been set up on the initiative of ordinary citizens. The coordinated, top-down campaign of historical revisionism dates back to 2012–14 – the beginning of Vladimir Putin’s third presidential term and the first phase of the armed invasion of Ukraine. The liquidation of Memorial, an organisation that was founded in 1989 to commemorate the victims of Soviet terror, and the full-scale assault on Ukraine in February 2022 marked the beginning of a new, neo-totalitarian phase in the Kremlin’s politics of memory, which now strives to secure a complete monopoly on shaping the narrative about the history of Russia and the Soviet Union in order to legitimise the ongoing war.

This narrative is driven by several objectives. It is designed to prevent any criticism of the increasingly oppressive Putin regime by comparing it with the repressive policies in the past, to discredit the regime’s opponents as enemies of the state and the people, and to affirm state terror and imperial conquest as evidence of Russia’s might. A narrow circle of Kremlin decision-makers arbitrarily defines the interest of the state, which is always put above the rights of the individual. In this context, they consider it essential to lie about history and erase material traces of ‘alternative memory’. This is because the latter prevents the dehumanisation and anonymisation of the victims of state violence, in particular the citizens of the countries that Russia now considers hostile, such as Poland and the Baltic states.

As part of the campaign to affirm state terror, which has been intensifying in recent years, Russian secret services and law enforcement agencies have explicitly invoked the legacy of the Soviet apparatus of repression. In one of the most recent manifestations of this trend, a statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky was unveiled at the headquarters of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) in Moscow in September 2023. It is a scaled-down copy of the monument that once stood on Lubyanka Square, whose toppling in August 1991 became a symbol of the fall of the totalitarian Soviet regime. At the unveiling ceremony for the monument, the head of the SVR, Sergei Naryshkin, noted that “Dzerzhinsky’s head faces the north-west, towards Poland and the Baltic states, where the threat to Russia lurks”. In his words, Dzerzhinsky was “a symbol of his time”, “a model of crystalline honesty, persistence and fidelity to duty”.

Another sign of historical revisionism is the semi-official rehabilitation of Stalin and the Stalinist period. This has been expressed in statements by top officials, including Putin, who have emphasised Stalin’s contribution to making Russia a great power, and in the growing number of monuments to the dictator that have been erected with the tacit approval of various levels of government. According to the independent project We Can Explain (Можем объяснить), there are some 110 busts and monuments to Stalin in 40 regions of Russia, but only ten or so date from the Soviet era, while 95 have appeared during Putin’s rule. In September 2023, a bust of Stalin and other criminals of the period was erected at the memorial complex for the victims of Stalinist repression in Mednoye (Tver oblast), where more than 6000 Polish victims of the NKVD are buried, in order to “reflect the realities of that era”.

This correlates with Russian society’s growing approval of Stalin in recent years: in a July 2023 poll by the independent Levada-Center 63% of respondents viewed him positively. Significantly, excessive criticism of Stalinism and, in particular, equating Stalin’s totalitarianism with Hitler’s, can be labelled as ‘rehabilitation of Nazism’, which is punishable by up to five years’ imprisonment under the Russian criminal code.

However, government officials at both the federal and regional levels rarely attend ceremonies unveiling monuments or busts of Stalin, which means that these are still largely grassroots and unofficial or semi-official events. Even in government circles, attitudes towards the glorification of Stalin are ambivalent, as positive assessments of this figure in society are often meant to express indirect criticism of the Putin regime, including widespread corruption. It is noteworthy that 43 Russian regions do not have even a single such artefact, and that the governments of some regions, especially those whose populations suffered as a result of the Stalin-era deportations, such as Chechnya and Ingushetia, have banned any commemoration of Stalin.

Prospects

As the invasion against Ukraine drags on and generates significant losses for Russia, both on the frontline and as a result of the Western economic sanctions which will aggravate the demodernisation of its economy over the long term, internal tensions in Russia are likely to escalate. In order to neutralise them, the Kremlin will not only step up its censorship and repression, but also ramp up its propaganda and mass indoctrination of the population, invoking the spectre of external threat, escalating its anti-Western and anti-Polish hysteria, and rallying society against the ‘enemies’ who have allegedly been bent on destroying Russia both in the past and in the present. The fight against historical memory will then intensify, which may have a negative impact on the Polish symbolic space in Russia. In particular, it is conceivable that the Russian government could take hostile steps towards the Katyn memorial complex, for example by changing its symbols or banning Polish officials from entering the site.

APPENDIX

Acts of vandalism targeting memorials to victims of repression in Russia in 2022–23

11 November 2022, Tomsk: unknown perpetrators vandalised a memorial to Polish victims of repression: the memorial plaque was torn off. Two days later, a plaque was ripped off the wall of a former shelter for children of deported Poles which operated in the 1940s. In the same month, a memorial to the Polish victims of the NKVD in the village of Belostok (Tomsk oblast) was also destroyed.

December 2022, Polozovo (Tomsk oblast): a cross and a plaque with the names of the Poles who had been murdered by the NKVD in 1938 were destroyed.

April 2023, Galashor (Perm krai): a monument to Polish and Lithuanian victims of persecution during the years of Stalinist terror was destroyed.

May 2023, Pivovaricha (Irkutsk oblast): a Polish monument and a Lithuanian cross commemorating the victims of the NKVD were dismantled; the oblast government said they had been erected illegally, so they were removed and would be kept elsewhere, but no details were given.

June 2023, Kostousovo and Oziornyi (Sverdlovsk oblast): monuments to the Polish exiles who had been deported from Volhynia after the annexation of Poland’s eastern territories in 1939 were destroyed.

June 2023, Rechka Mishikha (Buryatia): a monument to the Poles who had been sent to labour camps after the 1863 January Uprising and those killed during the 1866 Baikal Insurrection was destroyed. In recent years, residents had complained that the monument should not be there because of bad relations with Poland.

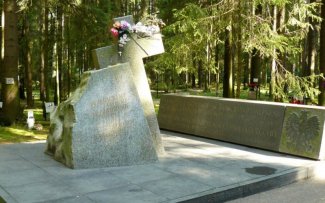

July 2023, St Petersburg (Levashovo cemetery): a monument commemorating the Poles who had been repressed in Leningrad during the years of Stalinist terror was removed; on 31 October, an installation erected on the site the day before by local activists from Memorial was taken down. The government of St Petersburg claimed that unknown perpetrators had destroyed the monument and that it had been sent for restoration, but refused to provide any details.

July 2023, Oreshek (Leningrad oblast): a plaque with the names of Polish and Lithuanian prisoners at the Oreshek fortress was dismantled.

August/September 2023, Rudnik near Vorkuta (Komi Republic): a concrete cross commemorating Polish prisoners of the Gulag was overturned. Local police blamed bad weather conditions.

September 2023, Yakutsk: a monument commemorating the Poles who had been victims of the deportations in the 18th and 19th centuries and the mass repressions in the 20th century, as well as prominent Polish researchers of Yakutia, was dismantled; back in the spring of 2023 nameplates had been removed from the monument.

October 2023, Vladimir (Knyaz-Vladimirskoye cemetery): a monument to the victims of Soviet repression (the Archimandrite of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church Kazimyr Maria Sheptytsky, the Lithuanian archbishop Mečislovas Reinys, the Polish politician Jan Jankowski) was dismantled. Local state-run media had made references to “commemorative plaques in honour of the fierce enemies of our country, guilty of the deaths of thousands of our compatriots”.